By: Ali Douraghy

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Science partnerships for development and diplomacy must put scientists at the forefront of engagement, says science diplomacy expert Ali Douraghy.

The scientific community was instrumental in facilitating US–Soviet dialogue during the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War in the latter half of the last century. Today, in the midst of a new political landscape,the United States is again turning to science for development and diplomacy.

In a landmark speech in Cairo, Egypt, last summer, US president Barack Obama pledged to develop a suite of science and technology initiatives to promote peaceful relations with Muslim communities.

The response from the Arab and wider Islamic world to Obama’s address was overwhelmingly positive. From Abu Dhabi to Rabat, people were encouraged to picture a promising future marked by new jobs, food and water security, and better relations with the United States.

Since then, many steps have been taken to move ‘science diplomacy’ forward. Science and technology offices at the US State Department and the US Agency for International Development are gaining unprecedented support. And the first three US science envoys have returned from visits to Muslim-majority countries with news of enormous potential and demand for scientific collaboration. The announcement of more envoys is around the corner.

But real change can only be achieved through tangible results that affect the daily lives of millions of people.

And while government-level dialogue undoubtedly opens channels of communication and shapes the framework for engagement, it is only the first step in building science partnerships that lead towards concrete development and diplomacy outcomes.

We urgently need to move to the next phase of science cooperation, which must take root at deeper and broader levels within Islamic and other societies.

Focus on people

The challenge is to put people — scientists and researchers — at the forefront of engagement.

The most urgent issues such as climate change, clean water and renewable energy are blind to political borders. Intensifying scientist-to-scientist exchange at the international level to address these shared challenges is a necessity — not only for US–Islamic world relations, but for all countries.

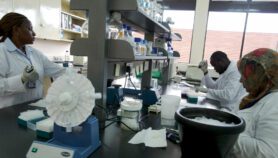

In part, this means building on initiatives that take US experts into developing countries to train local scientists. For example, the East African Regional Training Workshop, jointly sponsored by institutions in the United States and Tanzania, or the Whitaker International Scholars and Fellows Program, which funds biomedical engineers to conduct research projects overseas.

Offering more outlets to US faculty and graduate students for teaching or leading research in other countries will harness a new class of ‘science diplomats’.

But if it is important to open the door for more US scientists to go out, it is equally important to hold it open for foreign scientists to come in.

For these scientists, ensuring close and continued contact with US colleagues could lend them credibility, not only in their fields of expertise, but on other issues of regional and national importance. And these scientists can be effective ambassadors in their home countries — often interacting with hundreds of students each day.

Programmes such as the National Science Foundation’s International Research Fellowship — which brings early career scientists and engineers to the United States for advanced training — provide another valuable strategy for building science capacity abroad.

But restrictive visa requirements are a major obstacle to expanding such initiatives. Researchers are routinely denied permission to attend meetings in the United States and top-performing graduate students faced with starting a doctoral programme on a single-entry visa are increasingly turning to universities in Canada and elsewhere for their studies.

US border protection agencies must find a more suitable balance between homeland security and increasing access to scientists. Both are integral to national security.

New collaborations

There are other avenues that can be explored to enhance collaboration. International conferences, for example, can stimulate partnerships through sessions that are less defined by structured talks than by unscripted communication. Another potential forum activity could focus on indentifying funding mechanisms that support joint collaborations beyond the conference period.

Diaspora communities — such as the Algerian-American Foundation for Culture, Education, Science and Technology that aims to "promote progress in bilateral relations" — could also prove invaluable in ensuring that local needs and on-the-ground realities are accounted for in new US-led initiatives.

And reintroducing science attachés in US embassies could help spark new bilateral collaborations and strengthen existing activities. Take, for example, the role that science attachés played in bilateral space and desert explorations during the 1970s: familiar with scientific communities on both sides, a science attaché can coordinate dialogue that results in much more efficient use of available resources.

Science and policy communities across the globe must work together to create new initiatives and re-visit existing instruments to sustain collaboration and exchange between scientists.

These partnerships are vital to achieve real development and diplomatic results that permeate the daily lives of millions. International science collaboration must become stronger, before the momentum generated by science diplomacy fades and international science falls short on its promise.

Ali Douraghy is a 2010-11 AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow.