13/12/21

COP26 climate summit: facts and figures

By: Gareth Willmer

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Since the sun set on COP26 in Glasgow, reaction to the climate summit has been decidedly mixed. The general consensus among climate leaders from the global South, however, is that even though progress was made in some areas, key issues facing climate-vulnerable communities were ignored.

This facts and figures article takes stock of where the world is at following the meeting.

Concluding on 13 November – a day later than scheduled – 197 countries agreed a deal that the UK presidency insisted “keeps alive” the goal of limiting temperature rises to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Over the past two years, more than 150 countries submitted new or updated climate strategies, a five-yearly requirement under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

But temperatures are expected to rise well above 1.5 degrees under these strategies.

The International Energy Agency predicted that if national targets “are met in full and on time” they would hold global temperature rises to 1.8 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

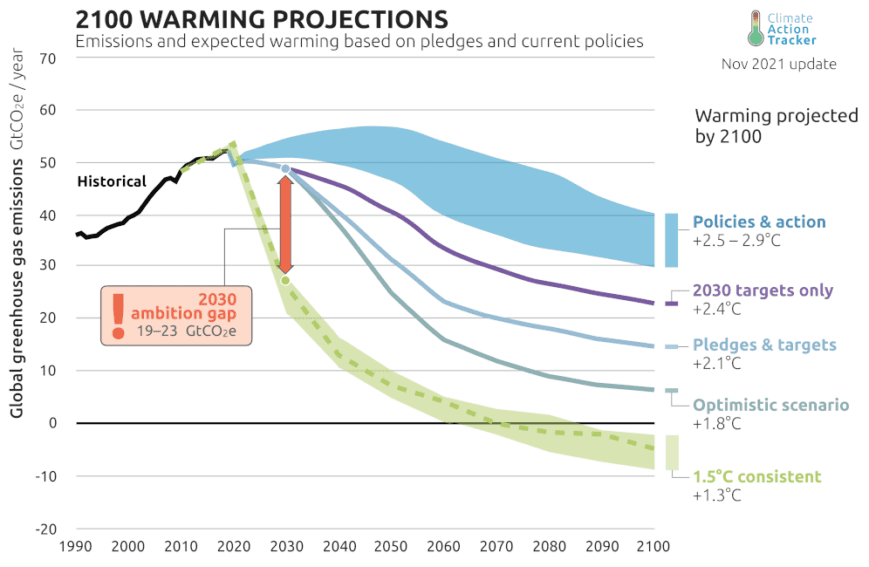

However, independent scientific body the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) said that while warming could be limited to 1.8 degrees under the most optimistic scenario, there was a “credibility gap” due to the incompatibility between national goals and actions planned up to 2030.

It estimates that existing pledges put the world on course for at least 2.4 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century, with policy implementation “advancing at a snail’s pace”.

Climate Action Tracker (2021). 2100 Warming Projections. November 2021. Available at: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/ Copyright: Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute. All rights reserved.

The heavy impact of missing the target was underlined by speakers at COP26. “We have 98 months to halve emissions. The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees is a death sentence for us,” said Shauna Aminath, environment minister for the Maldives.

Net zero and coal pledges

In what was widely seen as positive news, India, the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas emitter, set a target at COP26 for achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2070. Although this goes beyond the 2050 or 2060 goals of many other countries, the move came as a surprise given India’s previous resistance to net zero. It also means that all the world’s major emitters now have a net zero commitment in place.

At COP26, a handful of countries joined an existing coalition of states, companies and banks who say they will phase out coal power, with about 25 committing to end international public support for the unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022.

Despite these moves, some were disappointed that the final text in the Glasgow Climate Pact was watered down, moving from an aim to “phase out” to an agreement to “phase down” unabated coal power.

Outside the official negotiations, funds were committed to developing economies via the launch of the Accelerating Coal Transition programme, an investment of nearly $2.5 billion touted as a “first-ever effort to advance a just transition from coal power to clean energy in emerging economies”.

Launched by multilateral financing mechanism Climate Investment Funds and backed by financial pledges from the US, UK, Germany, Canada and Denmark, the first beneficiaries are expected to be South Africa, India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Additionally, South Africa entered into a political declaration with the UK, the US, France, Germany and the European Union to provide $8.5 billion over the next three to five years to enable a just energy transition in the southern Africa state.

Climate finance

But elsewhere, climate finance fell short. A pledge by developing countries at the 2009 Copenhagen summit to commit $100 billion in annual climate finance by 2020 has not been met, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) revealed ahead of COP26.

“The limited progress in overall climate finance volumes between 2018 and 2019 is disappointing,” said OECD secretary-general Mathias Cormann. “While appropriately verified data for 2020 will not be available until early next year, it is clear that climate finance will remain well short of its target.”

Costs for adaptation to climate change are also five to ten times greater than currently available public adaptation finance, according to estimates in a report by the UN Environment Programme. Furthermore, the report says the gap is widening, despite a growing volume of adaptation-related policies.

There was, meanwhile, frustration at COP26 when it came to funding for loss and damage – the irreversible harm from climate impacts – even though the summit saw the subject become more prominent.

While developing and small-island countries pressed for a new finance facility for loss and damage, developed nations pushed back on this and an agreement was instead reached to continue talking about the matter.

“We are disappointed that the proposed Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility is not included in the final decision,” said Sonam P. Wangdi, chair of the Least Developed Countries Group, which represents one billion people across 47 countries in Africa, Asia and Pacific, and the Caribbean. “We heard widespread recognition of this injustice, yet there was a failure to address it.”

Moves were also made at COP26 to plug at least some of the shortfalls in climate resilience and adaptation. A dozen governments pledged $413 million in funding to the Least Developed Countries Fund, while the Glasgow pact includes a goal for developed countries to double adaptation funding to developing countries to $40 billion by 2025.

Furthermore, over $450 million was pledged to locally led adaptation and $356 million to climate financing mechanism the Adaptation Fund.

Forests and methane

Major moves were announced in some other key areas.

Under the Glasgow leaders’ declaration on forests and land use, more than 140 countries, jointly possessing more than 90 per cent of the world’s forests, pledged to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030, while promoting inclusive rural transformation. The pledge quickly came under scrutiny, however, as civil society flagged doubts that signatories would follow through on the pledge.

At the summit, 28 indigenous peoples who represent communities that steward more than 80 per cent of the planet’s dwindling biodiversity were nominated as ‘knowledge holders’ to engage directly with governments.

In addition, more than 100 countries signed the Global Methane Pledge, agreeing to cut methane emissions by at least 30 per cent by 2030. As a powerful greenhouse gas, it is estimated that meeting the target would cut warming by a minimum of 0.2 C by 2050.

Yet given past events, many fears remain over whether these commitments and appointments are genuine, with delegates involved in negotiations warning that pledges would equate to “greenwashing” if parties failed to develop transparency and accountability measures.

Amid the widespread protests seen at the summit, some also questioned the representation of attendees. Campaigners Global Witness, for instance, revealed there were more than 500 delegates connected to the fossil fuel industry – a greater number than any individual country. This, Global Witness said, amounted to “flooding the Glasgow conference with corporate influence”.

Though current emissions targets look set to fall well short, countries agreed that they should return next year at COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, to “revisit and strengthen” their goals for 2030.

This article is part of our Spotlight on ‘The road to climate justice’

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk.