By: Giorgia Scaturro

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Giorgia Scaturro examines how phones, drones, satellites and computer games help spot and prevent conflict.

Technology has shaped modern warfare for decades. But it can be used to counteract conflicts as much as to ignite them. And this is reflected in recent trends in conflict and peace.

Map of global peace levels, measured with Global Peace Index score by country

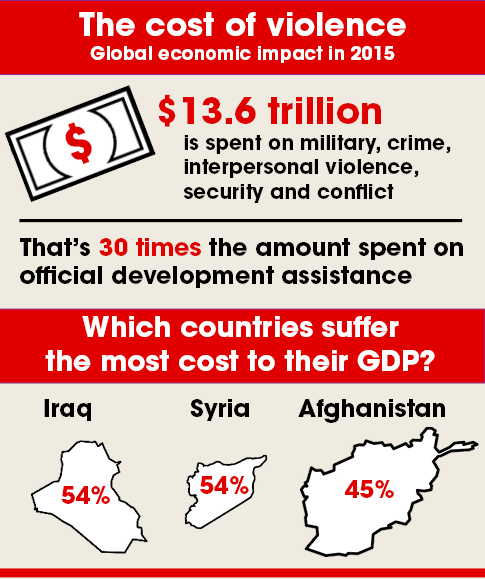

According to the Global peace index 2016, the world has become less peaceful over the past ten years. [1] In 2015, the economic cost of violence was US$13.6 trillion, which includes military and security spending, as well as losses linked to violence and conflict. This is equivalent to 13.3 per cent of the world’s GDP (gross domestic product). And a study on terrorism in cyberspace shows that the number of websites containing terrorist material rose from 12 in 1998 to 2,650 in 2003 and then 9,800 by September 2015. [2]

Parallel to these trends, technology is increasingly influencing how civil society and other institutions work to prevent conflict and build peace. It does this by offering creative ways to counteract conflict narratives (the stories people tell about conflict, foster networks against violence and increase the local and international impact of peacebuilders.

There are many examples of tech benefiting developing countries, especially where governments and economies are unstable — even in places with limited internet access. Simple tools such as text messages, for instance, can allow people to gather and share crucial information about violence and so help prevent conflict in their communities.

Leading the rising wave of technological innovations against conflict is the information and communications technology (ICT) sector with an influx of projects that see internet, mobile phones and other telecommunications devices as protagonists of a tech revolution for peace.

Defining peace

- Peacebuilding

-

This is a process that involves various measures designed to reduce the risk of lapsing or relapsing into conflict. This is done by strengthening national capacities to manage conflict and laying the foundations for sustainable peace and development. It creates self-supporting structures that “remove causes of wars and offer alternatives to war”.

According to Johan Galtung, founder of the discipline of peace and conflict studies, conflict resolution mechanisms should be part of the peacebuilding system and become a kind of reservoir, “just as a healthy body has the ability to generate its own antibodies and does not need ad hoc administration of medicine”.

- Peacemaking

-

This refers to measures taken to address conflicts as they occur. It usually involves diplomatic action to bring hostile parties to a negotiated agreement. Peacemaking efforts are generally undertaken by official or governmental entities such as envoys, groups of states or the United Nations, but may also come from others such as a prominent personality working independently.

- Peacekeeping

-

This is a role held by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations to help countries in conflict create the conditions for lasting peace.

- Peace enforcement

-

This refers to use of coercive measures, including military force, to end conflict. It requires the explicit authorisation of the UN Security Council. It is used to restore international peace and security in situations where the Security Council has decided to act in the face of threats to peace.

- Conflict prevention

- This involves diplomatic measures to keep intra-state or inter-state tensions and disputes from escalating into violent conflict. It includes early warning, information gathering and a careful analysis of the factors driving the conflict.

The emergence of ICTs

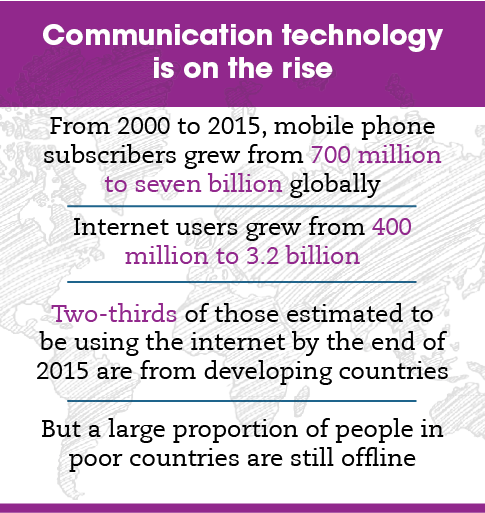

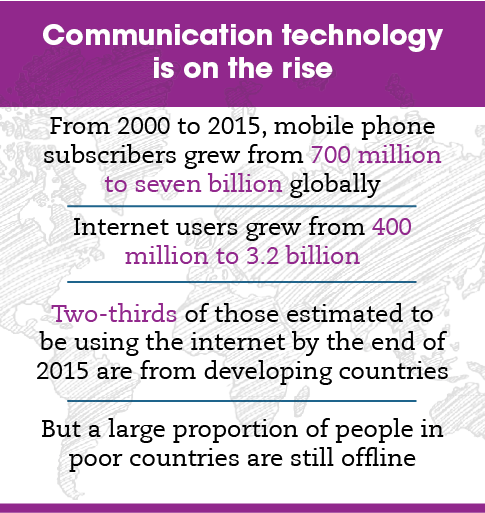

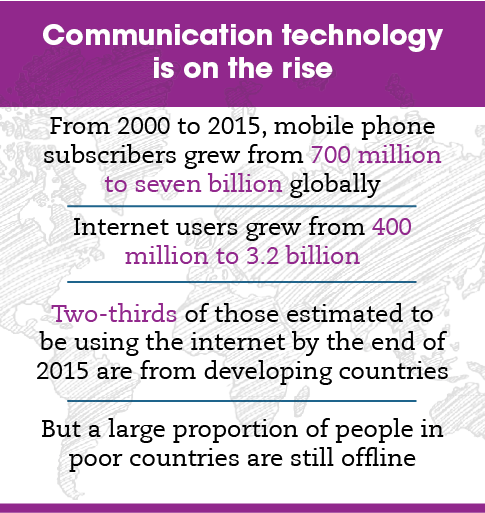

The wide availability of ICTs to people with limited financial resources and technical skills was a turning point for peacebuilders using technology. Over the past two decades, the increasing availability — and affordability — of internet and mobile phones have democratised information by putting new technology in the hands of the general public, alongside peacebuilders. This was amplified by the explosion of social media that mobilised people to challenge their governments, a high-profile example of which were the uprisings that led to the Arab Spring. Citizens use ICTs to have their voices heard and to coordinate actions that challenge their relationship with governments. They also use them to share initiatives that promote better knowledge of local circumstances that can be used to prevent conflict.

The potential benefits of ICTs to promote peace and prevent conflict received global attention with the Tunis Commitment, a consensus statement adopted after the UN-sponsored World Summit on the Information Society in 2005. [3] The statement notes the value of these technologies for institutions too, as a tool for early warning, humanitarian action, peacekeeping, peacebuilding and reconstruction.

The UN is at a relatively early stage of integrating new technologies into peacebuilding and security, according to a discussion paper published in April by the Independent Commission on Multilateralism. [4] The UN Development Programme, for example, has started to implement programmes such as the Uwiano platform, a free text message (SMS) service allowing people to report threats of violence. This was deployed in Kenya during the constitutional referendum in 2010, receiving 20,000 messages with no violence reported during the event.

NGOs, citizen and governmental institutions have been more active, in some cases collaborating with the UN. The ICT4Peace Foundation is one example. It champions the use of ICTs for peacebuilding through reports and strategic guidance, and works closely with the UN to strengthen its capacities to map, share and use data across various agencies and locations.

This led to some pioneering applications. One was the use of high-resolution satellite imagery in 2007 to document the genocide in Darfur in western Sudan as part of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Crisis in Darfur project, a collaboration with Google Earth. Satellite evidence is also at the core of Amnesty International’s ongoing Eyes on Darfur initiative. In Kenya in 2008, the free, open source software Ushahidi became the “testimony” (its translation from Swahili) of post-election violence, gathering witness reports from the community via the internet and text messaging. This was a triumph of crowdsourcing crisis information for social activism: the reports were compiled into an online map that offered a more complete picture of the violence than any one organisation could have produced.

Ushahidi has become an inspirational story of how technology can empower local people to provide first-hand information in fast-moving crises. This is now the mission of citizen journalists who use ICT tools to document and tell unreported stories in difficult and restricted situations, such as conflict zones. Eyewitnesses equipped with smartphones can produce timely video and audio reports, and these can be shared with the rest of the world via digital platforms such as social media, blogs, wikis, podcasts or even WhatsApp.

Gathering data for early warning

The role technology can play in preventing, responding to and recovering from conflict is as diverse as the digital tools and apps available to users. One function relates to data collection and sharing: ICTs can help gather information in conflict-prone areas and build a solid knowledge base from which to respond.

This takes many forms: mobile phones with text message reporting tools (such as RapidSMS and FrontlineSMS); geographic information systems (GIS) and platforms for satellite imagery (such as the crowdsourcing software Ushahidi, QGIS, Google Earth and Google Maps); photo and video monitoring; and social media channels (such as Facebook and Twitter).

The past few years have seen rapid growth in the number of digital platforms to crowdsource, manage and visualise data. These are helping to generate vast numbers of data sets, including big data, which can be used to understand local contexts and identify possible conflict indicators. The ultimate goal is to build models that can predict conflict, provide early warnings and lead to prompt intervention.

One example is the Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN), established in 2002 in East Africa to prevent and mitigate violent conflict. It claims to have helped significantly reduce violent conflict, particularly along the Kenya-Uganda as well as Ethiopia-Kenya-Somalia borders.

There are several case studies on pilot projects that came after CEWARN and introduced tech-based early-warning systems in various parts of the global South, including Sudan-South Sudan and Colombia. [5] These demonstrate the benefits of ICT data, but also highlight some weaknesses. On the one hand, surveillance through digital platforms has helped police and governmental agencies reduce homicidal violence in Latin America. In Sudan and South Sudan, on the other hand, ICTs’ value in preventing conflict from local disputes generally depended more on how familiar each user was with the technology than with the technology itself. In general, innovative technologies enhanced crisis response only if they produced ‘actionable data’ out of the masses of data available.

Because of such mixed results, some experts remain sceptical about the impact of tech-enabled monitoring systems, unless they are matched by effective response mechanisms (Box 1).

Box 1: Lord’s Resistance Army crisis tracker: a model system? |

|

Matthew Levinger, international affairs professor and formerly with the Academy for International Conflict Management and Peacebuilding, is one of many who say that response mechanisms are needed alongside reporting technology to have any effect on the ground. Not doing this is tantamount to having an emergency phone line to report a fire but no fire brigade to put it out, he says.

Levinger argues that much of the response to potential conflict must come from people working locally. So the most critical thing when deploying technology is to think about whether the information sharing will truly enhance local capacity to respond more effectively. The ideal scenario, he says, is to have a ‘horizontal’ system where information is shared at a local level but also reaches ‘vertically’ to international organisations that can apply diplomatic pressure or provide resources to respond more effectively. The LRA crisis tracker is one model. This early-warning network is used in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo to record the presence of and incidents of violence by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebel group. People can use long-range, two-way radios to report attacks, killings and abductions. The information is published on a website, accessible to international agencies including the UN peacekeeping forces, but it is also available to local organisations who have better awareness of what is happening in their area. |

In a report commissioned by the ICT4Peace Foundation, Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, argues that the UN should take the lead in designing and implementing ICT solutions that strengthen information sharing. [6] The report also highlights the absence of useful metrics to evaluate the success of ICTs, and says that because of this gap, impact should be measured by whether these technologies have improved the lives of people affected by conflict.

The proliferation of data harvesting techniques is also paving the way for research into using ‘big data’ for peacebuilding. One project of the Data-Pop Alliance, for instance, looks at how big data can be used to prevent urban violence in Bogotá, Colombia.

However, collecting and storing all sorts of data come with risks that touch on controversial internet governance questions. For example, some observers warn that using big data could compromise privacy, or even threaten the security of individuals if data falls into the wrong hands. This is at the centre of a recent working paper by the Independent Commission on Multilateralism, which offers recommendations on applying new technologies in peace, security and development, and on developing a framework governing their use. [4]

Information sharing to calm tensions

Another peacebuilding function of digital platforms enabled by ICTs is to allow information sharing. This happens through social media, blogs (such as iRevolutions, Diary of a Crisis Mapper or Groundviews) and online forums, alongside older technologies such as radio. Sharing also helps create an alternative to conversations that incite hate and violence on the web and on the ground, and can calm tensions and build online networks of peacebuilders. Kenya is home to some of the most successful cases, and many of these cases focus on tackling rumours.

During the 2013 elections, the NGO Sisi ni Amani (‘we are peace’ in Swahili) reversed the trend of rumours, misinformation and incitement to violence using the same technology that was spreading them. It developed a text messaging platform in consultation with grass-roots activists and sent messages to disrupt those conversations, as well as Nelson Mandela quotes and civic education messages. More than 65,000 Kenyans received messages and 92 per cent of respondents to a survey said the messages helped keep the peace. [7] According to Jessica Heinzelman, former chair of Sisi ni Amani, what made the NGO special compared with other SMS-based initiatives was community engagement: working with local groups to explain the project meant everyone knew what it was and people had a relationship with the organisation.

Non-profit organisation the Sentinel Project has established various platforms to counter rumours and hate speech. One is WikiRumours, which prioritises and responds to misinformation. The Sentinel Conflict Tracking System visualises conflict around the world. Hatebase, an online repository of hate speech, has almost half a million entries across numerous locations and languages (Figure X). And rumour verification service Una Hakika used text messaging, voice calls and trained volunteers on both sides of the conflict between the Orma and Pokomo ethnic groups in Kenya’s Tana Delta.

It [technology] wouldn’t work if we didn’t have local people on the ground, in the communities, committed to disarming conflict.

Timothy Quinn, director of technology at the Sentinel Project

An evaluation of the project shows it led to more than 300 rumour investigations and interventions over the course of a year, reaching an estimated 45,000 people in the target area. [8]

Most common hate speech targets(by number of terms referring to specific group characteristics)

New technologies also enable peacebuilders to create digital networks that coordinate and enhance their work in conflict prevention (table X).

Table 1. Some successful digital networks for peacebuilding

| Name | Tools | Target area |

|---|---|---|

| All for Peace Radio | Radio | Israel, Palestine |

| All for Peace Radio helps to bridge the divide between Palestinian and Israeli society through stories of interest to both. A joint initiative of Palestinian NGO Biladi and Givat Haviva, a Jewish-Arab peace centre | ||

| Crack in the Wall | Social media | Israel, Palestine |

| Crack in the Wall is a Facebook community for conversation and engagement between families who have lost a family member as a result of the Palestinian-Israel conflict | ||

| FrontlineSMS | Text messaging, the cloud | Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria and elsewhere — but the platform can be downloaded anywhere |

| FrontlineSMS helps NGOs in developing countries improve their communication, enhance local radio programming and assist peacebuilding. Has been adapted to provide election monitoring to prevent violence, for instance in Burundi and Kenya | ||

| Groundviews | Website | Sri Lanka |

| Groudviews is a website for citizen journalists to offer perspectives on governance, human rights, peacebuilding and other issues | ||

| HarassMap | Text messaging | Egypt |

| HarassMap is a reporting system fighting sexual harassment in Egypt | ||

| Internews | Online and broadcast media | |

| Internews trains media professionals and citizen journalists to use innovative media and multi-language networks to dispel rumours in conflict zones, for example Nile FM community radio station in South Sudan | ||

| Peace Direct | Blogs, mobile technology | Parts of Africa and Asia |

| Peace Direct supports local actions against conflicts by connecting with local peacebuilders and running educational campaigns | ||

| PeaceFactory | Video | Middle East |

| PeaceFactory runs viral campaigns on Facebook that encourage people to post messages of love and friendship across conflict barriers | ||

| Search for Common Ground | Audiovisual media | Africa, Asia, Europe, Middle East, North America, South-East Asia |

| Search for Common Ground initiates shared solutions to destructive conflicts through community dialogue. For example, Radio for Peacebuilding Africa aims to develop, spread and encourage the use of radio broadcasting techniques and information for peacebuilding. In 2012, it ran a video competition asking Lebanese young people to Shoot Your Identity | ||

| Soliya’s Connect Programme | Web-based virtual exchange | Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, Europe and North America |

| Soliya's Connect Programme is an online cross-cultural education programme between university students around the world, connecting young people in the West with predominantly Muslim societies | ||

Challenges to using tech for peace

The successful examples testify to technology’s power to build peace, challenge those in power and canvass knowledge to prevent conflict. But there are also ethical and operational challenges.

The ethical danger is that overrelying on tech-based peacebuilding programmes could lead to a shallow level of engagement — what some call ‘clicktivism’ or ‘slacktivism’ — that some believe undermine established practices in activism. People can now support peace by merely clicking on a link, as with petitions on popular websites such as Avaaz and Change.org. This type of digital activism can garner support rapidly and cheaply. But it also risks being unstable: short-lived, and difficult to grow into a sustained long-term effort. Traditional grass-roots networks for peace activism require physical infrastructure and take time to build trust. By the same token, relying exclusively on digital networks is unlikely to sustain a movement through lengthy political processes — and that partly accounts for the rise and fall of the Arab Spring.

The operational challenges relate to the inclusion of disadvantaged groups and the digital divide. The 2014 Web Index report shows that, while internet use in high-income countries has soared from around 45 per cent to 78 per cent since 2005, in low-income countries it has remained below ten per cent year after year. [9] In the poorest countries, basic internet access remains over 80 times more expensive (in terms of purchasing power) on average than in the richer countries — while internet use is ten times lower. [10]

But the role of technological tools in peacebuilding depends on access as well as connectivity. An estimated 4.4 billion people — more than half the world’s population — have no internet access and they are mostly poor, female and living in rural areas in developing countries. [9] In addition, 5.1 billion people are not on social media, and more than 1.7 billion women in developing countries do not own a mobile phone. [11,12]

And inclusion goes beyond technology. Adam Lupel, vice-president of the International Peace Institute, says exclusion and social inequality can create conflict — suggesting that one way to prevent conflict is to improve how diversity and inequalities among groups are managed.

We know that the more inclusive societies, with better access to justice and governance, are the more peaceful societies. There should be investment in new technologies to improve democratic governance, also in terms of commitment to keeping the lines of communication open. Governments should not be afraid of information. Digital development and democratic development should go hand in hand.

Adam Lupel, vice-president of the International Peace Institute

Some efforts are being made in this direction. One example is the Open Government Partnership, which brings together 69 countries to harness open and innovative technologies to strengthen governance and support civic participation.

Data for better action

When it comes to using ICTs to gather big or small data to provide an early warning of potential conflict, success depends on engaging people to act.

In Nigeria, for example, International Alert is collecting large amounts of data — around 23 million tweets and one million news articles in the first year — to spot spikes in violent incidents and assess the sentiment around conversations between specific groups. Analysis then allows the organisation to highlight the influential people it can recruit to assist local peacebuilding.

The bulk of digitally created information, small and big data, keeps growing exponentially — but what is the concrete impact this can have on peace? Dan Marsh, head of technology at International Alert, charts the many opportunities and the limitations of using data to improve early warning and the knowledge that informs peacebuilding projects.

Other projects are also tackling the challenge of using data to improve response:

● The Georgia-based Elva Platform combines data collection tools such as text messaging, smartphones and web reports with data analytics and visualisations. One of its practical applications is the Social Peace Index, which captures the results of an ongoing survey on people’s perceptions about safety or confrontations witnessed in local areas in Libya. The idea is to empower community leaders to monitor and manage conflict tensions during the political transition following the 2011 overthrow of President Muammar al-Gaddafi.

● In Thailand, the Coalition Center for Thai Violence Watch is building an online crowdmap of protest sites based on citizen reports that volunteers verify on the ground. Collected information includes the views of protesters, community members, the police and emergency workers at each site. Pictures and videos of clashes can also be securely uploaded. In case of violence, the centre issues alerts to protest leaders, peace activists and emergency services. Collected data is also used to assess future risk of violence.

● In the war-torn province of South Kivu in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the Voix des Kivus system uses mobile phones to obtain high-quality, verifiable and real-time information in hard-to-reach areas about various events, including disease outbreaks, crop failures and conflict. The system is built on the FrontlineSMS text messaging software and merges messages into a database. It then automatically generates graphs and tables that are added to weekly bulletins sent to bodies such as development organisations that have received clearance from the project.

Satellite technologies, such as the ones deployed in the Satellite Sentinel Project in Sudan and South Sudan, are also improving. Geospatial technology is now used to monitor human rights and prevent conflict, documenting violence in almost real time. Satellite images provide high-resolution evidence of crimes against humanity, potentially enabling action by private citizens, policymakers and international courts (Box X). When violence erupted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2009, for instance, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) helped the UN in the difficult task of assessing the devastation and civilian impact of rebel attacks in remote areas. Using satellite images, AAAS provided evidence of the ongoing violence, which supported efforts to increase civilian protection.

Satellite imagery, mobile phone apps and systematic data storage are also recommended by a new protocol addressing the difficulties of collecting evidence on sexual violence in conflict.

Box 2: Does technology offer hope for Syria? |

|

Syria is currently the least peaceful country in the world. The Syrian conflict is the world’s deadliest and most violent, producing the highest number of displaced people: more than half its population. It is also marked by aggressive terrorist propaganda by the militant group Islamic State (ISIS), which has mastered a sophisticated social media outreach.

Terrorist organisations use digital channels such as YouTube as their official channel to broadcast information about new groups, as well as to shock the West with HD videos of coldblooded murders. In this scenario, where political efforts seem to be failing in bringing the conflict to an end, how can technology help? Several tech-based humanitarian projects monitor this conflict, some producing real-time updates. This has created an information-rich environment about the Syrian conflict, but also one in need of advanced analytical tools. Companies such as First Mile Geo aim to fill this gap by helping humanitarian agencies and others to visualise and analyse relevant data, including the movement of armed groups. The Carter Center has been working in Syria since the uprising began, looking for a political solution. It does this mainly through the Syria Conflict Mapping Project, which analyses humanitarian conditions, relationships between armed groups and conflict events such as aerial bombardments. The centre’s Syria Transition Dialogue Initiative engages with a network of Syrian interlocutors working to find common ground to help the transition to peace and future governance. The war in Syria is also pushing boundaries in the exploration of digital alternatives to putting armed forces on the ground — through video systems, motion detectors, unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) and other tools that facilitate monitoring and observation. However, the implication is that drones are becoming part of a risky conflict dynamic. |

Technologies of the future

As technological innovation widens the horizons of peacebuilding, there are some digital technologies to watch and others that are starting to make an impact. They involve video games, virtual reality and drones.The UN Alliance of Civilisations (UNAOC) and UN Development Programme, with support from social enterprise Build Up, have launched PEACEapp, a competition that promotes digital games and apps to encourage cultural dialogue and conflict management. The online community Games for Peace uses video games to bridge the gap between young people in the Middle East and other conflict zones, using shared virtual experiences to build trust.

The Enemy — an immersive virtual reality experience that combines artificial intelligence and neuroscience research on empathy — brings users face to face with ideas of enemy and empathy, deepening their knowledge of long-standing conflicts.

Virtual reality projects are already being piloted by medical and humanitarian organisations working in disaster response. Some say such schemes can help train local communities on how they respond to emergencies, including conflicts.

Meanwhile, despite being renowned as instruments of war, aerial drones have a growing peacekeeping role. [14] These remotely piloted aircraft systems can be used for surveillance — to keep the peace and protect civilians — or they can be used for humanitarian micro mapping.

Technologies cannot counter conflict in isolation — they are woven into complex political, economic and social systems. And because of those complex relationships, technologies are both the result and the cause of social change. According to Kofi Annan, former UN secretary-general, ultimately they can help promote the mutual understanding that is “an essential factor in conflict prevention and post-conflict reconciliation”. [15]

Giorgia Scaturro is a freelance journalist covering science and technology based in London, United Kingdom. She can be contacted at [email protected] and @giorgiawired

This article is part of our Spotlight on Technology for peace.

Upcoming peacebuilding events |

|

The Build Peace Conference is an annual meeting that brings together practitioners, activists and technologists from around the world to share experiences and ideas on using technology, arts and research for peacebuilding and conflict transformation. This year it will take place in Zurich from 9-11 September. |

References

[1] Global peace index 2016 (Institute for Economics and Peace, June 2016)

[2] Gabriel Weimann How modern terrorism uses the internet (United States Institute of Peace, March 2004)

[3] Tunis Commitment (International Telecommunication Union, November 2005)

[4] The impact of new technologies on peace, security, and development (Independent Commission on Multilateralism, April 2016)

[5] New technology and the prevention of violence and conflict (International Peace Institute, April 2013)

[6] Peacebuilding in the Information Age: Sifting hype from reality (ICT4Peace Foundation, January 2011)

[7] Seema Shah and Rachel Brown Programming for peace: Sisi ni Amani Kenya and the 2013 elections (Center for Global Communication Studies, December 2014)

[8] Drew Boyd and others Una Hakika: Mapping and countering the flow of misinformation in Kenya’s Tana Delta (The Sentinel Project, December 2015)

[9] The web and rising global inequality (World Wide Web Foundation Index, 2014)

[10] Six digital technologies to watch In: World development report 2016: Digital dividends (World Bank, 2016)

[11] Global cooperation In: World development report 2016: Digital dividends (World Bank, 2016)

[12] Connected women 2015 — Bridging the gender gap: Mobile access and usage in lowand middle-income countries (GSMA, February 2015)

[13] Six digital technologies to watch In: World development report 2016: Digital dividends (World Bank, 2016)

[14] Helena Puig Larrauri And Patrick Meier Peacekeepers in the sky: The use of unmanned unarmed aerial vehicles for peacekeeping (ICT4Peace Foundation, September 2015)

[15] Daniel Stauffacher and others Information and communication technology for peace: The role of ICT in preventing, responding to and recovering from conflict (UN ICT Task Force, 2005)