By: Aisling Irwin

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

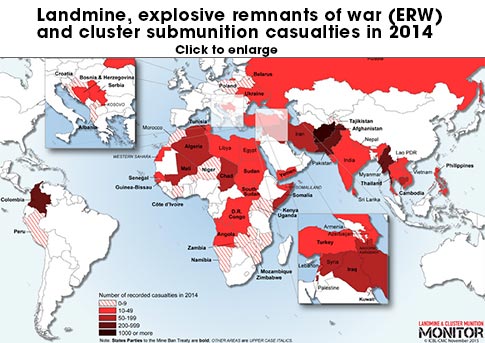

Since 1975, landmines have killed or maimed more than a million people, 80 per cent of them civilians. The disabilities caused by mines are devastating. And, in countries where access to physiotherapy and prostheses is poor — that is, most countries where landmines exist — the lifelong impact on wellbeing is extreme.

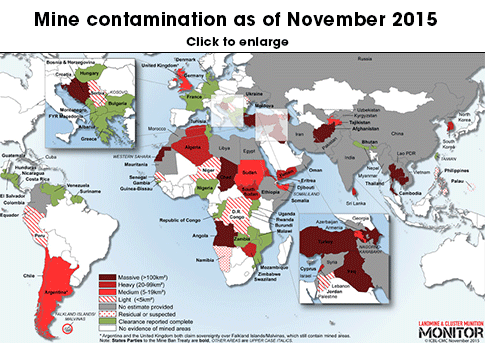

Last week’s Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention conference in Switzerland was a reminder that the signatories hope to have eliminated mines within nine years. In that time, more than 100 million mines must be cleared from over 57 countries — and more unexploded bombs are appearing in countries such as Syria and Yemen every day, despite international treaties banning them.

Yet, while scientists regularly invent new ways of detecting mines, their relationship with mine clearance communities is often poor. This is partly because well-meaning inventors often bombard clearance organisations with wacky ideas that don’t appreciate the complex realities of their work.

To find out what can be done, I rang Yann Yvinec, of the Royal Military Academy in Belgium. He has just finished coordinating TIRAMISU, a multimillion dollar project designed to bring scientists and mine clearers together to solve problems identified by the clearance community itself, rather than what scientists think they need.

Yvinec says the key was to bring onboard those involved in demining right from the start. The 26 research institutions and engineering companies involved in the programme were guided not just by a scientific board but also an ‘end-user board’ — those who will use the technologies — at every stage of the project.

They also brought in a technology marketing company to help analyse why deminers might not use new designs. This assessment and conversations with mine clearers highlighted the need for technology to be simple to use, robust — and cheap.

Through this early interaction, scientists realised several further truths. First, says Yvinec, deminers regularly risk their lives, so caution and infallible tools are far more important to them than speed or flashy gadgetry.

Second, a human inching along with a metal detector is, though slow, very accurate. “Metal detectors work very well now. There’s little you can do to improve them,” Yvinec says. “Improving detection itself is not where you can achieve the most in demining.”

Instead, the area crying out for more and better solutions is all the work you have to do up to the point of removing landmines — the less glamorous and inefficient work at the beginning to narrow down the target area, before the clearers go in, for example. “The clearers can spend days and days and weeks without finding a single mine,” he says.

The toolbox of innovations that TIRAMISU came up with includes techniques for distinguishing which suspected areas are actually mined.

A device under development tests the air above a suspected minefield for the scent of explosives. And there is an armoured tractor — cheaper, smaller, lighter and more manoeuvrable than its tank-like predecessors — for clearing vegetation and performing other tasks for demining teams.

TIRAMISU has now finished, but mine clearance organisations have already begun buying the new technologies. And the conversations haven’t stopped. “We are trying to build a centre of excellence, a community to keep the link between all of us and the mine action communities,” says Yvinec.

Aisling Irwin is a science journalist and writer based in the United Kingdom, and a former SciDev.Net news editor. She is contactable on [email protected]