By: Ben Deighton

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A mission of 40 NASA scientists is heading to Senegal at the start of August, to help with the planning for the final stage the New Horizons space mission to observe the outer planets. It will also strengthen science in the country, says David Baratoux, the chairman of the African Initiative for Planetary and Space Sciences.

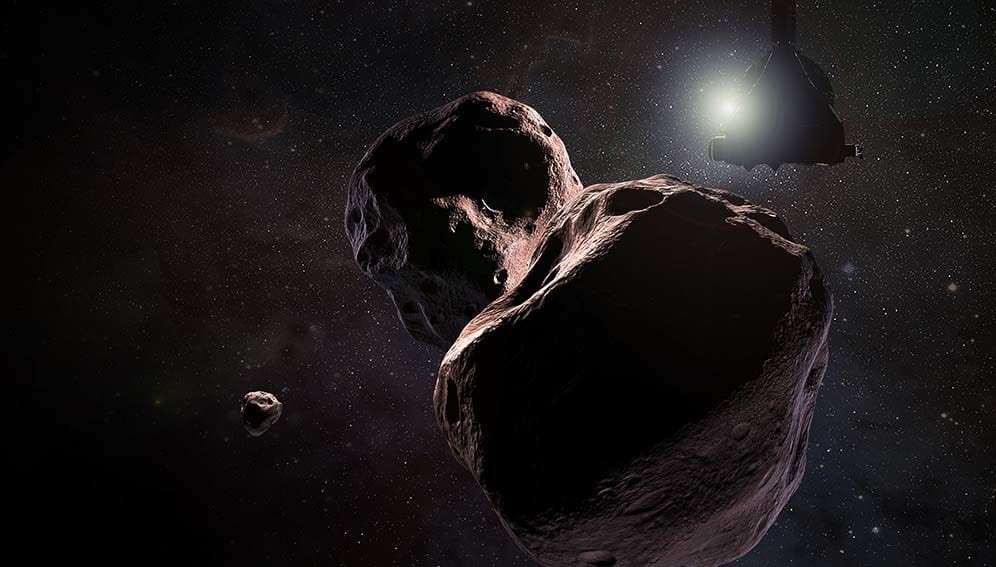

After flying past Pluto in 2015, the US space agency’s New Horizons probe is now heading for an object the size of a small city, known as MU69. To do this, the NASA team is travelling to Senegal to exploit a stellar occultation — where a space object is directly lined up with a distant star — which will allow them to observe MU69 using powerful telescopes.

As well as providing valuable data on the shape of MU69, the mission aims to establish links between NASA astronomers and scientists in Senegal, according to Baradoux, who spoke to SciDev.Net on the sidelines of the EuroScience Open Forum in Toulouse, France, this week (July 7).

What impact will this mission have on research in Senegal?

This is a real collaboration between the people from NASA, a group of eight French astronomers supported by CNES (the French national space research centre), and … 21 Senegalese scientists who will participate in this observation. Each of these Senegalese scientists will have a chance to join the NASA groups and participate in the training sessions which will have occurred before the actual events. There will be two nights dedicated to training so they will have a chance to know how to observe occultation, and moreover, they will establish very close connections with these NASA people. So we hope from that collaboration to establish long-term collaboration between Senegalese scientists and NASA astronomers.

“It can be a life-changing event to participate as a child or as a teenager in such an event,”

David Baratoux, IRD, France

.

You are based at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD — Institut Français de Recherche pour le Développement ) in France. What is your role in this project?

I am at the moment the chair of the Africa Initiative for Planetary and Space Science which was launched in 2017, originally to demonstrate that there was a large enough community in Africa willing to start research, higher education projects in astronomy, and space sciences and planetary sciences. We also wanted to demonstrate that there is international support for this idea [of promoting space science in Africa], which means that there were enough scientists all over the world ready to build new partnerships with African colleagues. So that is where we are now.

We have made this demonstration [of support for space science in Africa]; we have more than 20 African institutional organisations who have endorsed the initiative; we have more than 350 individual scientists who have also endorsed this initiative, half of them being from the African continent. And we will organise one or two workshops before the end of the year to help to define the science strategy for the development of astronomy and space science, planetary science in Africa.

What will that strategy look like?

The strategy for planetary and space science in Africa will, of course, depend on the countries. What we would like to see is projects based on local expertise, skills, local facilities. For instance, in Morocco you have one of the most advanced astronomical observatories on the continent, excluding South Africa. So in this particular case the Moroccan astronomers can think about what they would like to develop, in terms of research, with what they have. In other countries they have potential impact craters, meteorites … other countries may want to access NASA data from the exploration of the solar system. They can simply use their internet connections and they are skilled in geophysics, in remote sensing, to work on that data. So it really depends on the local expertise. We are hoping to see what people want to do and match it with experts around the world.

What is the exact timetable of the occultation?

The occultation will take place during the night of the third of August to the fourth of August. It will occur early morning, before sunrise. There will be a lunar eclipse just a week before, on the 27th of July, and some of the French and NASA scientists will be already there for public outreach, taking advantage of this lunar eclipse. There will be conferences and events related to the occultation.

Where will the 21 telescopes come from?

About five tonnes of equipment is being shipped to Senegal. Some of this equipment has already arrived, and more will be on the way this week. So we will have 21 telescopes, plus cameras, plus some equipment around these telescopes. We will also use 21 cars to scatter the telescopes at different points of observation. The idea is to find the best place to observe, maybe just 24 hours before the occultation takes place, because we need to deal with the weather — August in Senegal is the beginning of the rainy season so it will be a huge concern to make sure we have a clear sky to make the observations. So we rely on the weather forecast by the Senegalese agency for weather forecasting, and to make sure that we select the 21 sites at the very last minute to deploy the telescopes.

What will happen after these observations have taken place?

What I hope is that, like we [now] have the first PhD student in astronomy in Senegal, [that] maybe there will be others. At the moment if you want to do a PhD in astronomy in Senegal it is difficult to find supervision, so the easiest way to start something in research in astronomy is to organise a co-supervision of students involving foreign collaboration. By establishing such kinds of collaboration we would like to offer more opportunities to have other PhD students in astronomy. This has to be done, of course, in coordination with the project of the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation in Senegal.

What impression will these scientists make?

The 21 groups of astronomers that will be scattered all around the country will be in small villages [with] people around them. That will be maybe the first time for them [the children] to see telescopes. They will come and they will be able to share, to discuss with the scientists. What I like with my American colleagues is they really come in the spirit of having an impact on Senegalese science. They don’t just want to come, make the observation, and go back. They are really concerned to participate in the development of astronomy in Senegal, and they are willing to share this experience with people. It can be life-changing to participate as a child or as a teenager in such an event. So we are really hoping that maybe a few, maybe a few tens of children will decide to become scientists after this event.