By: Sally Murray

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

In the lofty world of architecture prizes, it’s often the more extraordinary designs that win accolades. But when Chilean Alejandro Aravena won the Pritzker Prize — the ‘Nobel prize of architecture’ — last week, it put the spotlight on a very different kind of architecture: one that prioritises people over prestige.

Aravena’s Elemental studio advocates “architecture as a shortcut to equality”: an approach guided by the demands of a global housing crisis. From a low-cost housing project in the Chilean desert to post-disaster housing for displaced people, this is architecture that brings ordinary people into the design process and works to the budgets of the poor.

“this is architecture that brings ordinary people into the design process and works to the budgets of the poor”

Sally Murray

The world is crying out for such urban design. Developing countries face a huge housing shortfall: people are moving to cities at an unprecedented rate, while 200 million (two-thirds) of urban households are already in slums. Houses that the poor can afford are generally flimsy, single storey, poorly located, overcrowded and with insecure tenure.

Firms have been getting creative to meet the challenge: we’ve seen 3D-printed houses in China, semi-permanent flat-pack shelters for Syrian refugees, and prefab compressed straw walls and cheap sanitary coating for dirt floors in Rwanda. A housing lottery for thousands of affordable flats in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, is one state-led innovation. But many governments are dragging their feet and the gap between people’s needs and the housing available remains vast.

Incremental construction is important because the poor can’t access credit to buy the ‘finished house’ they’d like up-front. But, like everyone, poor people like to expand and otherwise improve their houses as resources become available from savings, windfall income and broader social networks.

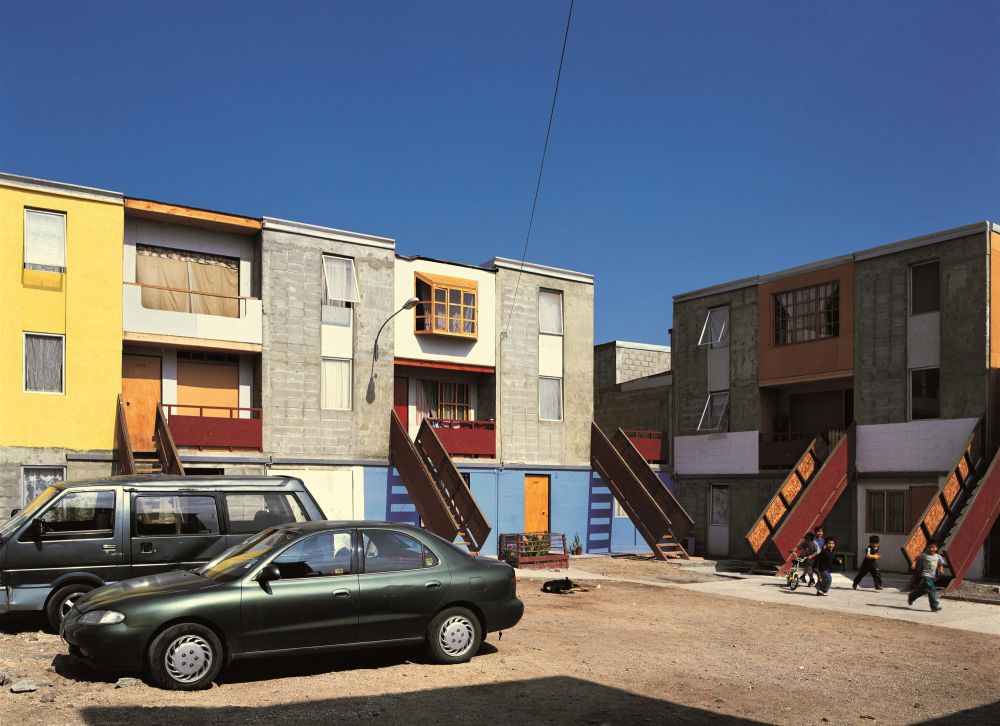

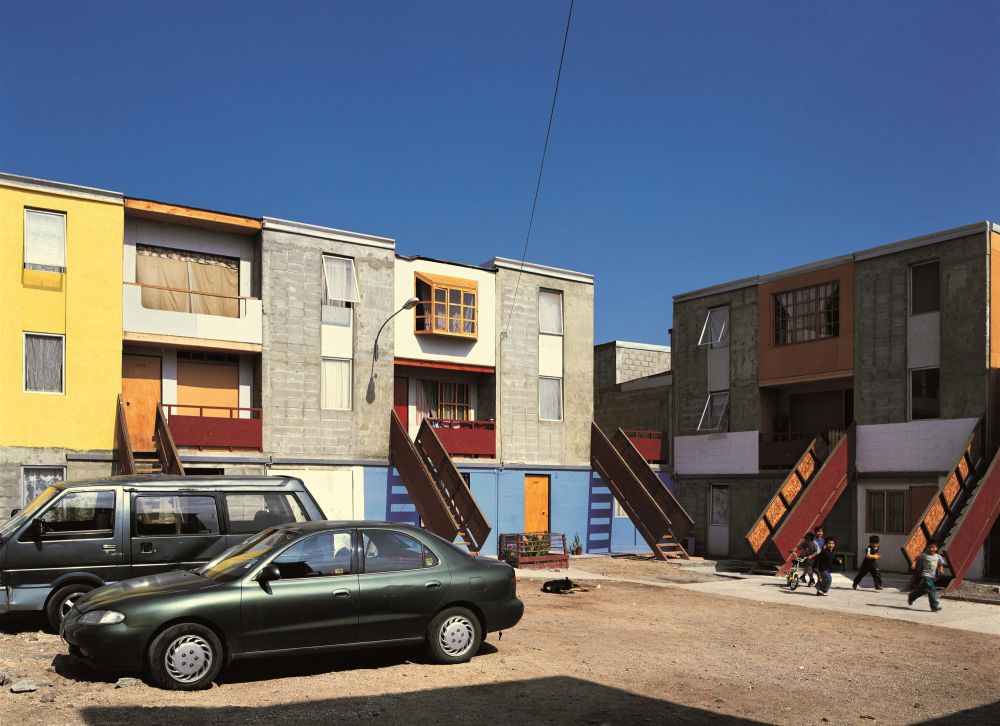

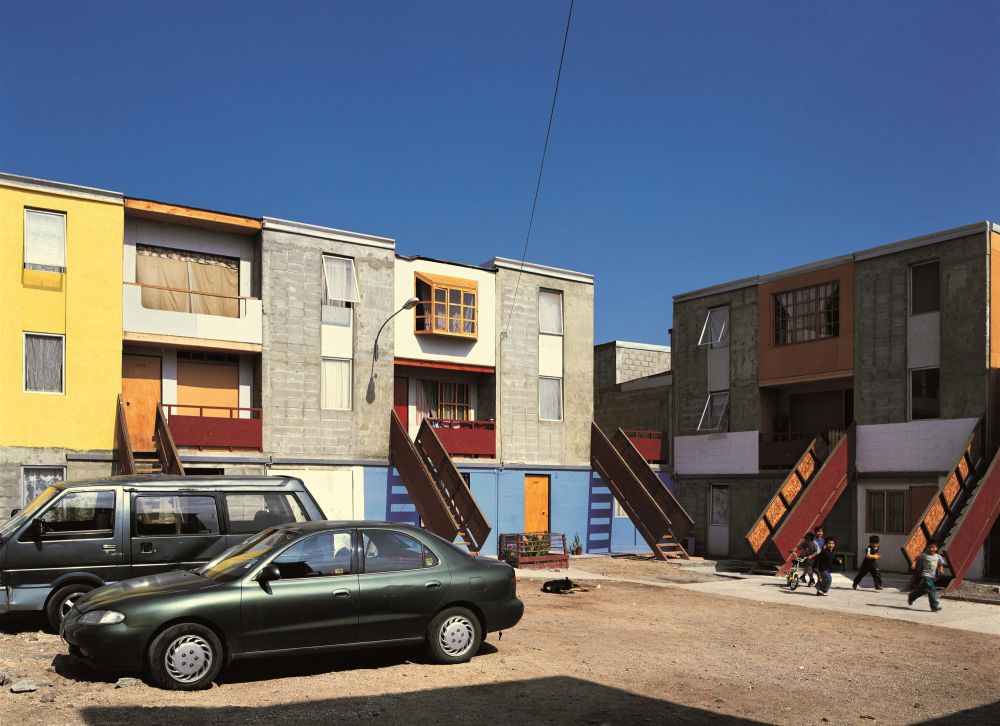

Aravena’s housing projects provide recipients with literally half-finished houses: one side is un-built, and the interior is bare, with only basic amenities and no finishings. Home owners add to it when they can afford to.

This simple approach makes good-quality housing accessible to poorer people. It also provides them with personalised homes they are invested in. In contrast, anonymous, grey high-rises leave residents no space for expansion, while slums entail insecure land rights and inadequate infrastructure, leaving little incentive for home improvements.

An example of Elemental’s ‘half of a good house’ concept, in Quinta Monroy housing project, Chile

Cristobal Palma/ELEMENTAL

The houses of Quinta Monroy, Chile, at a later stage, after residents have added features to them

Cristobal Palma/ELEMENTAL

An interior of an Elemental house at Quinta Monroy, Chile, before residents move in

ELEMENTAL

A Quinta Monroy home interior, after residents have moved in and developed the space

ELEMENTAL

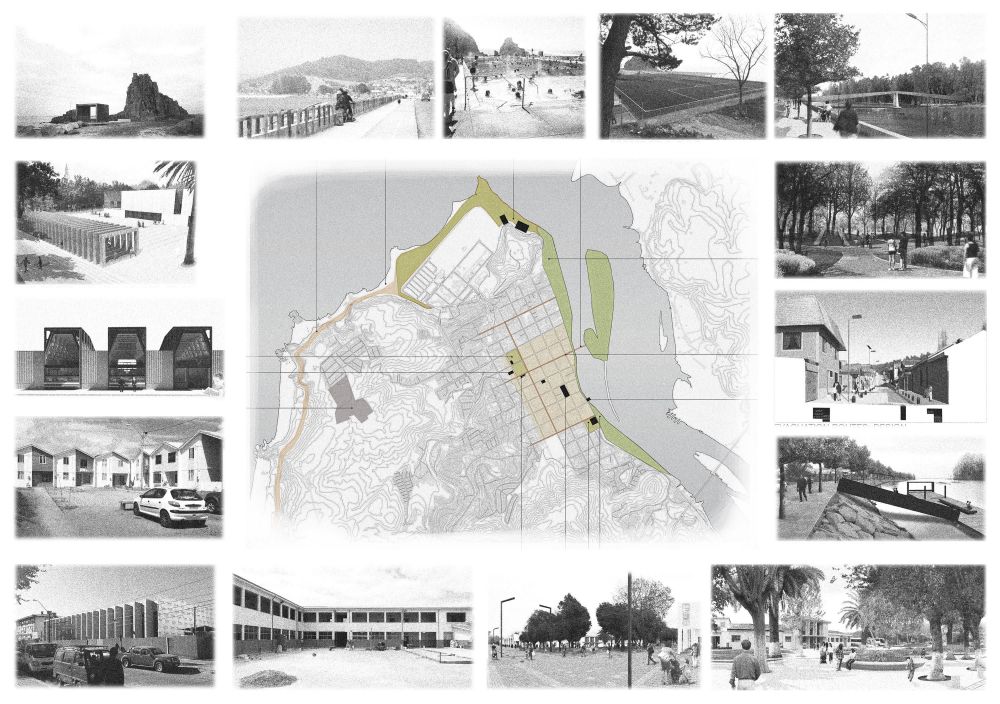

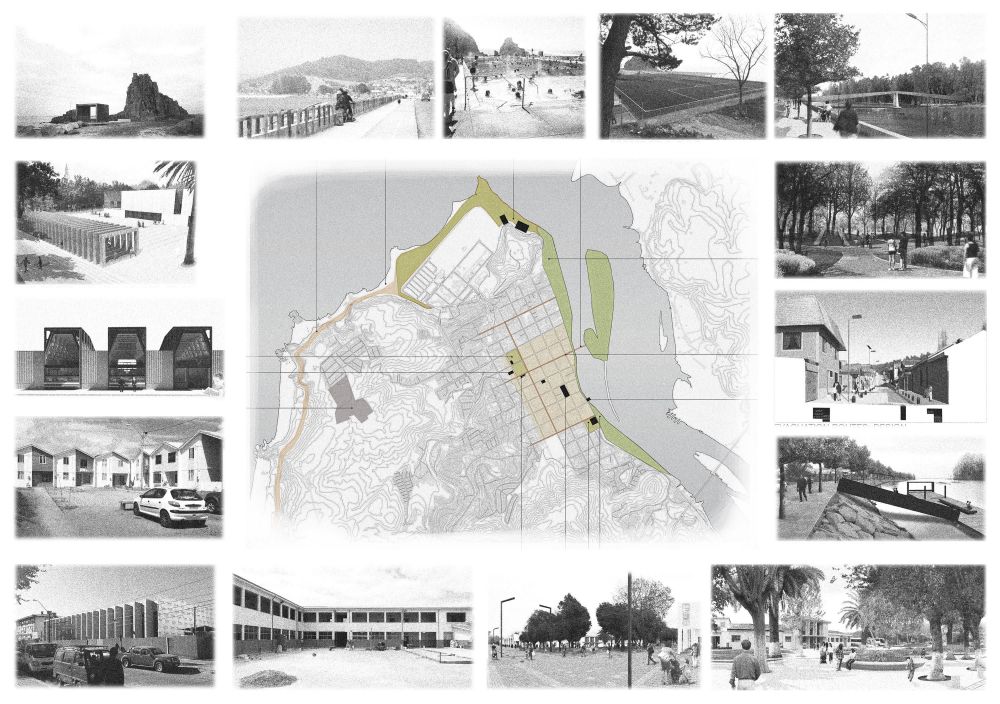

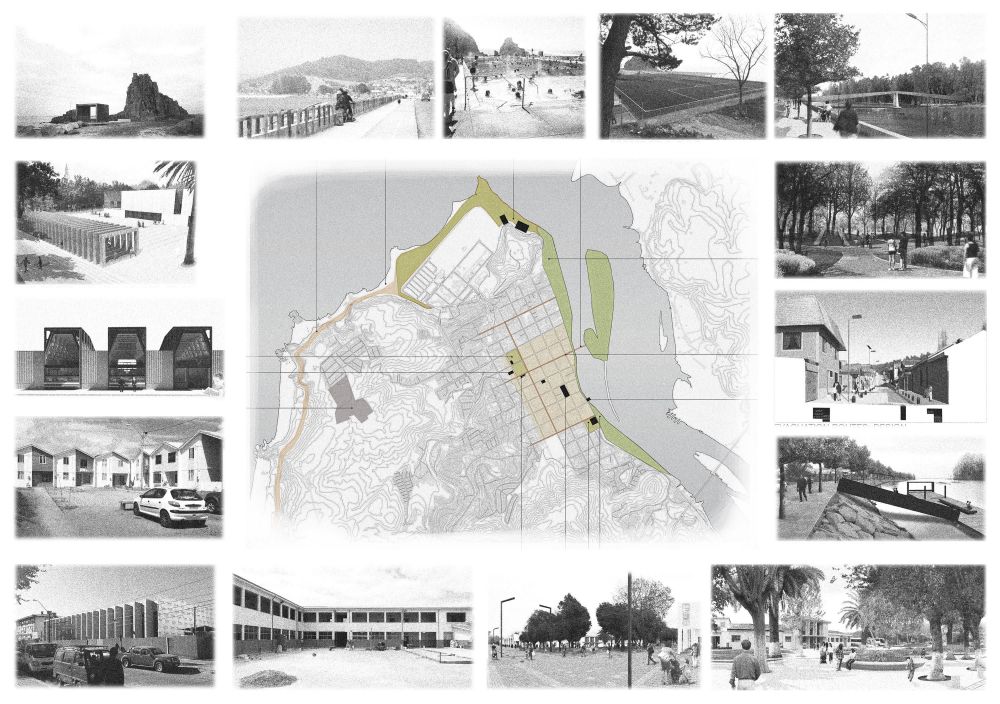

Post-tsunami reconstruction plan of Constitución, Chile. On 27 February 2010 an 8.8-magnitude earthquake and tsunami hit Chile. Constitución was one of the worst hit cities

ELEMENTAL

Some of the design ideas for post-tsunami reconstruction in Constitución, Chile, showing housing, parks and public buildings. The earthquake and tsunami caused damage to at least 400,000 homes

ELEMENTAL

Part of the post-tsunami reconstruction plan for earthquake-affected Constitución, Chile

ELEMENTAL

The Villa Verde housing project, for people affected by the 2010 earthquake and tsunami

ELEMENTAL

The Constitución housing development in Chile

ELEMENTAL

But to Aravena’s grey slabs, residents have added rooms, colour, foliage, furniture and finishings to make attractive neighbourhoods that are culturally appropriate and meet residents’ idiosyncratic needs.

The model can deliver other benefits. By building houses in rows and providing the upper floors — or the foundations for these so that they can be built over time — the technique can encourage dense developments that reduce land consumption, allowing poor residents to live near jobs, amenities and transport, where land is more expensive.

So far, incremental build designs have been slow to penetrate mass housing projects, and haven’t been embraced by most developing country planners — or by most architects, who tend to look for an immediately attractive finished product.

But there’s a need to branch out from tired and ineffective models of mass social housing to embrace not only new materials and technologies, but also new architectural norms about the meaning of ‘good housing’. If this year’s Pritzker Prize leads to wider recognition of this simple (and ancient) technique’s attractiveness and necessity, I hope more governments and firms start trying it — and demanding it — to finally make quality living conditions for a growing urban population a reality.

Sally Murray is a country economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC), a research institution based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with the University of Oxford, both in the United Kingdom. She works in Rwanda, overseeing the IGC Rwanda’s research on urbanisation, energy, public sector performance and tax. She can be reached via Twitter: @sally_bm