By: Ilan Kelman

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Ilan Kelman examines the history, overlaps and conflicts between climate change, development and disasters.

By the end of 2015, three global policy processes will have set the stage for how the world responds to major challenges facing humanity in the years to come. A voluntary agreement to tackle disasters was reached in Sendai, Japan, in March; the voluntary Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were finalised in New York, United States, in September; and now, the world is moving towards the December climate change negotiations, aiming to agree an international treaty in Paris, France. [1,2]

Science has long indicated that these three topics are connected. Separating them may be unnecessary and even counterproductive. Yet this policy separation is now more or less entrenched for the foreseeable future.

But this does not preclude using scientific evidence to identify actions common to all three. This would conserve resources, avoid one process causing or exacerbating difficulties for another, and encourage measures that align two or more objectives.

The idea of enfolding climate change within wider development topics has been present since climate change emerged as an important global concern. [3] Yet scientists and politicians sometimes put forward climate change as the overarching or most important issue. They argue that the changes are so vast, swift and devastating that we must focus resources and attention on them.

Sometimes, climate change is indeed the main threat (see box 1). But examining it in the wider context of development does not downplay its importance. Rather, it highlights how climate change connects with and influences other development concerns.

Box 1: Where climate change dominates |

|

Some communities are being forced to move due only to climate change. Residents of Takuu and the Carteret Islands in Papua New Guinea are planning their relocation, as are the villagers of Newtok and Shishmaref in the US state of Alaska. In Papua New Guinea, rising sea levels have led to flooding, contaminating crops and water supplies with salt water. And in Alaska, increasingly intense storms are eroding the coast, casting buildings into the sea. Other low-lying locations, such as coastal Bangladesh, Tuvalu and Kiribati in the Pacific, and the Maldives in the Indian Ocean also face potential mass upheaval.

But the picture is more nuanced than ‘drowning islands and coasts’ or ‘climate change refugees’. For example, many of the people threatened with relocation do not wish to be labelled ‘refugees’. [4] Instead, they ask for external resources to determine for themselves if, how, when and where to move. [5] The impacts of sea-level rise on atolls and coastlines are not always clear: some locations might erode but others might even grow as the sea rises; or other climate change impacts, such as ocean acidification or contaminated fresh water, might make locations uninhabitable for some living organisms before sea levels rise significantly. [6] |

Past to present

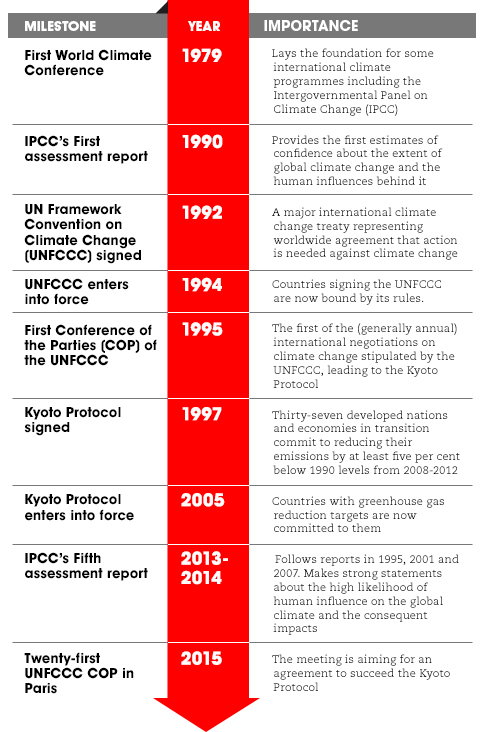

The suggestion that emissions of greenhouse gases influence the atmosphere, altering climate (see box 2), dates back to at least the nineteenth century. [7] Major science reports, published in the 1970s, then provided the foundation for policy processes including the UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change). [8-11] They also prompted further scientific assessments, including the UN mechanism through which governments assess the state of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (See figure 1 for major milestones.)

Box 2: What is climate change? |

|

Human activities release carbon dioxide and other ‘greenhouse gases’ by burning coal, oil, and natural gas to generate electricity, using petrol to power vehicles and raising large herds of livestock. These gases accumulate and trap heat in the atmosphere, raising the planet’s average temperature and affecting the earth’s climate system. Human-induced changes that reduce the planet’s ability to absorb these greenhouse gases reinforce their impact. For example, widespread deforestation means fewer trees to absorb carbon dioxide as they grow. Oceans also absorb carbon dioxide, which reacts with water to make an acid. Ocean acidification is one of the impacts of climate change: more carbon dioxide in the air means more acidic oceans, potentially harming marine and coastal ecosystems. There are many ‘feedback loops’ — some contributing to climate change and some lessening it — which makes understanding climate change more complex. Warming the seas makes them more or less able to absorb carbon dioxide, depending on location. [12] Large volcanic eruptions block sunlight when they throw dust into the atmosphere, but the effects are temporary. The effect of clouds is difficult to model, whereas the loss of glaciers and ice sheets through melting reduces the amount of sunlight reflected away from earth. And melting permafrost releases trapped natural greenhouse gases. Yet, despite the complexities and uncertainties, overall the science is clear: the planet is undergoing a rapid warming with a significant contribution from human activity. |

Climate change impacts

Climate change influences weather patterns and their extremes. Warmer air holds more water, making intense downpours more likely. This means that storms are likely to become more intense in many parts of the world due to climate change — but are also less frequent in some cases. This includes tropical cyclones. [13,14]

Climate change is predicted to increase ocean acidity and raise sea levels. A global average sea-level rise of roughly one metre up to 2100 seems likely because water expands as it warms. If large, land-based ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica melt, then sea level could rise by several metres, inundating major cities.

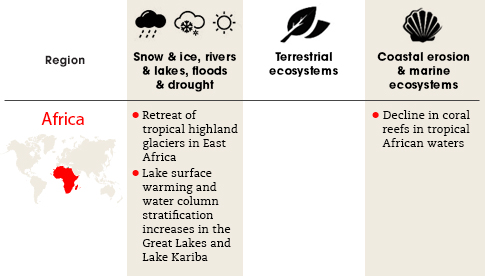

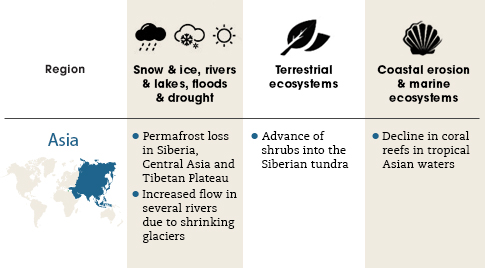

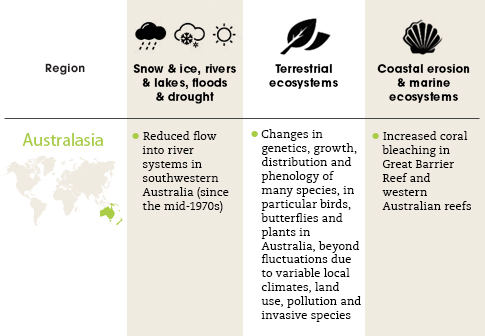

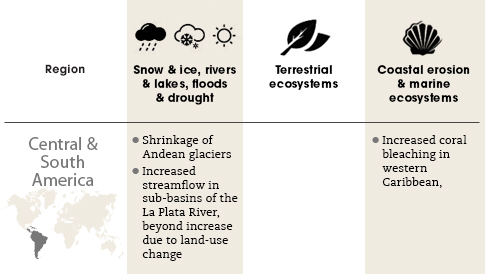

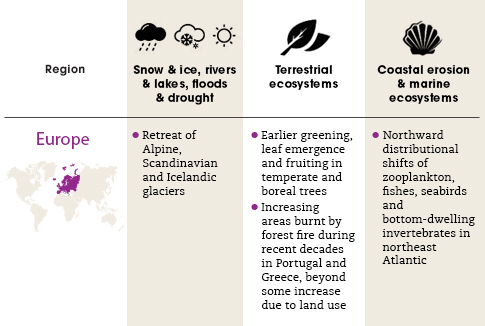

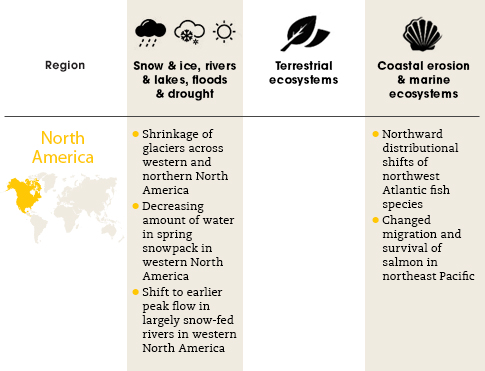

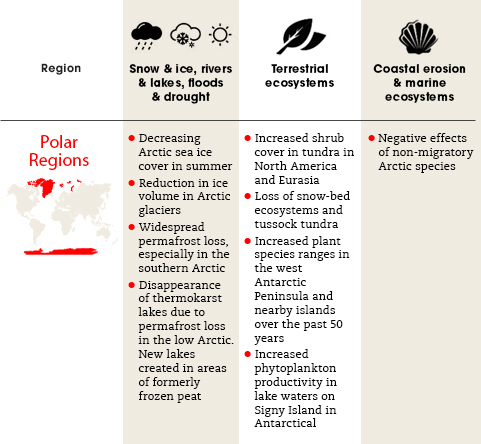

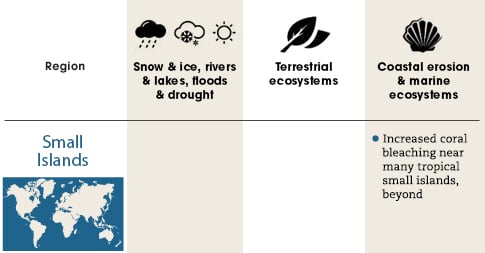

Warmer climates will radically change ecosystems, possibly spreading human, animal and plant diseases into new locations. Changing rainfall will affect freshwater supplies, with some places receiving more and others less, in turn affecting food supplies. Some locations will gain substantially from improved agriculture while others could see local food sources being wiped out (figure 2). [15]

Figure 2. Impacts attributed to climate change with high confidence

- … in Africa

-

- … in Asia

-

- … in Australasia

-

- … in Central & South America

-

- … in Europe

-

- … in North America

-

- … in the Polar Regions

-

- … in the Small Islands

-

Climate change impacts will also vary depending on development-related factors. A hazard, like a storm, is not enough to cause a disaster — vulnerability is also part of the equation. A weather-related event becomes a disaster when it harms people, property or social relationships, usually because political and development processes have not helped people reduce their vulnerability. Climate change itself cannot cause a disaster.

Pulling apart

Despite these connections, funders, institutions and governance structures frequently single out climate change and treat it independently. This is partly because of how the science and policy of climate change has evolved. Many scientists research only a particular dimension of climate change, and many treaty negotiators specialise in a single topic to ensure that agreements are detailed and robust.

In terms of policy, this separation is also reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 13 calls for “urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”, and singles out the UNFCCC as “the primary international, intergovernmental forum for negotiating the global response to climate change”.

The IPCC and UNFCCC processes have also separated climate change from other development topics. And they have separated climate change mitigation (cutting emissions or ‘capturing’ carbon) from adaptation (dealing with climate change impacts, which is part of disaster risk reduction).

Clear overlaps

Despite the separation between the international policies for climate change, disaster risk reduction and development goals, science backs their full integration so they can complement and support each other.

One reason for this support is that dealing with climate change’s impacts is not really different from disaster risk reduction and sustainable development processes. In fact, all climate change adaptation sits within wider development objectives. Protecting coral reefs and restoring coastal mangroves, for example, can reduce disaster risk: coastal vegetation sometimes absorbs wave power, so infrastructure may experience less damage. Upgrading sewer systems and planning for better urban water drainage count as adaptation — but are needed irrespective of climate change.

Similarly, all mitigation sits within wider environmental objectives. Efforts to lessen dependency on fossil fuels, by using renewable energy sources and reducing energy demand, predate the climate change agenda. Health was a primary reason: reducing air and water pollutants and promoting more active lifestyles are standard approaches for improving wellbeing. The 1973-74 Oil Embargo and other political events also spurred on these attempts, which foundered as politics and oil prices changed.Many scientists have long supported joint action on mitigation and adaptation [16-19] to help avoid exacerbating existing development problems. For example, protecting a forest as a ‘carbon sink’ (for mitigation) by forbidding access means local forest users lose food and income opportunities, making them more dependent on expensive and less reliable supplies from outside their community. [20] Projects for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) programmes may carry this hidden cost.

Hydropower also shows the risks of separating climate change from wider development concerns. Constructing large dams can reduce fossil fuel consumption by providing renewable energy. But in Egypt, China and many other countries, creating vast reservoirs has forced people to move as their homes are submerged. [21] Increasing control over water flow also leads to a false sense of security, making people less likely to take measures that reduce their vulnerability to drought and flood. The impacts of a major flood or drought are then worse than if people had continually been dealing with more frequent, smaller hazards. [22]

One key lesson is that disasters are not just unusual extremes, but also represent the chronic, underlying vulnerabilities in most people’s lives. In other words, over the long term, many disasters emerge from poor development or underdevelopment, influenced by policy and practice that lead to vulnerability. Discrimination, power, financial structures and culture are some of the reasons why people do not always act on knowledge about reducing vulnerability.

The opportunities for making these connections become clearer when climate change is seen as being one influencer of hazards among many, rather than as an entirely separate sector.

Opportunities for joint action

Even with a policy separation so entrenched that integration seems unlikely until at least 2030 (when the SDG and disaster risk reduction agreements expire), actual interventions could overlap more in practice by building on existing science (table 1).

| Table 1 : Policy links between disaster risk reduction, climate change and development goals | ||

|---|---|---|

Action |

Connections |

|

| Building typhoon- and flood-resistant housing in Vietnam using appropriate technology in shelter design. [23] | The work is already needed as part of disaster risk reduction, irrespective of the need to adapt to increased risks from climate change. | |

| Teaching lower-caste women how to swim in southern India. [24] | Melds climate change adaptation, flood risk reduction and social equity in the same activity. | |

| Using fishers’ knowledge to deal with environmental and social change in Barbados. [25] | Places climate change within the context of wider development and change to deal with them all simultaneously. | |

| Addressing coastal erosion in the Seychelles, using coastal management and land use planning. [26] | Addresses climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction at the same time, and promotes community spirit by creating public space. | |

Occasional conflicts

Some mitigation and adaptation actions can clash with wider development aims.

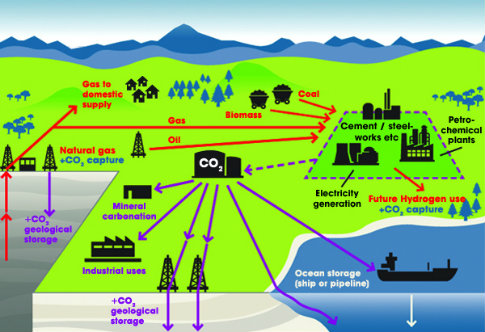

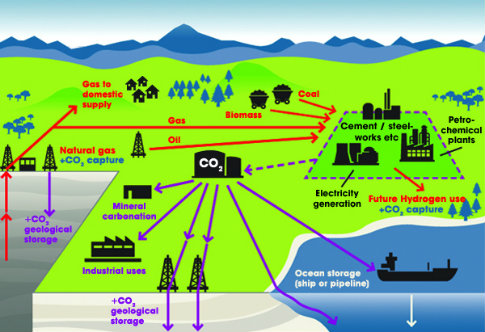

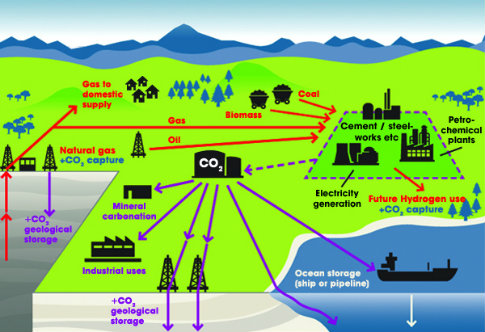

For mitigation, techniques for capturing greenhouse gases, called carbon capture and storage (CCS), trap emissions at power plants for storage underground or underwater (see figure 3).

Objections to the technique include the possibility of the gases leaking back into the atmosphere, the capital costs of constructing power plants with CCS included and the energy use of capturing and pumping the gases. [27]

More fundamentally, CCS contradicts the long-standing principle of pollution prevention, which holds that the cheapest and most effective way of dealing with pollution is to avoid creating it in the first place. Applying this principle, which was developed to deal with environmental problems such as acid rain, suggests that changing to clean energy and curbing emissions by reducing energy use are preferable to techniques such as CCS.

If wider development concerns are not considered, adaptation measures can sometimes foster ‘maladaptation’. For example, if heatwaves in major cities become more frequent and extreme, then adaptation might entail using more air conditioning and fans, which are energy intensive, contributing to the root causes of climate change. Instead, appropriate building design and materials, including natural ventilation techniques, can be cheaper and more flexible.

If wider development concerns are not considered, adaptation measures can sometimes foster ‘maladaptation’. For example, if heatwaves in major cities become more frequent and extreme, then adaptation might entail using more air conditioning and fans, which are energy intensive, contributing to the root causes of climate change. Instead, appropriate building design and materials, including natural ventilation techniques, can be cheaper and more flexible.

Creating a future

Climate and emissions scenarios are based on modelling. The vast amounts of earth-observation data being collected help to continually refine and calibrate climate change models, but our limited processing and analysis abilities mean uncertainty continues. In addition, vested interests often seize on the healthy debates within climate change science to undermine mitigation and adaptation efforts. Placing climate change within wider development contexts can help to overcome both barriers to action.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment process is due to start soon, with a newly elected chair, and the relevant reports will probably be released by 2022. Although the IPCC process continues to view climate change as a stand-alone scientific discipline, many other initiatives produce research documenting areas of overlap with wider concerns. [28]

These publications could be used to move climate change science and policy into a wider context. This is a challenge and an opportunity for the Sixth assessment report and the new IPCC chair. One solid way to become more interdisciplinary would be by adding a mechanism for incorporating local, indigenous and traditional knowledge of climate change impacts and responses into IPCC reports.

However, the biggest immediate policy milestone is the negotiations at COP 21, taking place in Paris, France, this December. The future of intergovernmental climate change action, within or external to development and disaster risk reduction, depends on any agreement reached in Paris and its subsequent ratification.

Nonetheless, many climate change science, policy and practice initiatives occur beyond the UNFCCC and IPCC. In September 2014, the UN hosted a climate summit in New York, United States, where organisations from the public, non-profit and private sectors pledged action in eight areas: agriculture, cities, energy, financing, forests, industry, resilience and transportation. [29] It emphasised how much can happen beyond the UN and the IPCC to deal jointly with climate change action and development that helps people’s day-to-day lives.

Ilan Kelman is a reader in risk, resilience and global health at the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction and the Institute for Global Health, University College London, United Kingdom. He can be contacted via http://www.ilankelman.org/contact.html and through Twitter @IlanKelman

This article is part of our Spotlight on Joint action on climate change

| Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Carbon capture and storage (CCS) | A process for trapping and storing carbon dioxide emissions, otherwise known as sequestration. Suggested storage locations are usually deep underground, deep within mountains or under the ocean floor. In-ocean storage is no longer deemed acceptable because it would contribute to ocean acidification. The carbon dioxide would be stored as a gas, as a supercritical fluid (neither gas nor liquid) or in mineral form. Biological uptake, such as through tree growth, is theoretically CCS, but the term typically refers to non-biological processes. |

| Climate change | According to the scientific definition, given by the IPCC, climate change is a change in the properties or parameters of the earth’s climate, measured statistically and attributed to any source, natural or human. The policy definition, given by the UNFCCC, is the same but attributes it only to human activity. |

| Climate change adaptation | The process of adjusting to climate change by reducing harmful impacts (by moving infrastructure off expanding floodplains, for instance) and enhancing any benefits (by switching to crops preferring the new climate which could include a different growing season). Adaptation can be technical, such as improved climate control in buildings; social, such as accepting workplace clothes suitable for a range of temperatures; or a combination, such as improving indoor climate control but only turning it on during hot or cold extremes. |

| Climate change mitigation | The process of reducing climate change emissions by using less fossil fuels, helping forests hold more carbon or even capturing and storing carbon. Mitigation can be technical, such as developing and using more fuel-efficient vehicles; social, such as travelling less; or a combination, such as improving internet access and accepting video conferencing rather than face-to-face meetings. |

| Conference of the Parties (COP) | The decision-making body for the UNFCCC, which has met in most years since 1995. Members are mainly states who are parties to the UNFCCC and they negotiate agreements on climate change mitigation and adaptation, such as the Kyoto Protocol. |

| Disaster | A situation in which a hazard combines with vulnerability causing damage that people cannot handle without outside support. The situation’s scale could be local, national or international. |

| Disaster risk reduction | Policies and actions targeting the root causes of disasters so that actual and potential damage are reduced. Disaster risk reduction can: tackle a hazard, such as by erecting walls outside a town to deflect avalanches; focus on vulnerability, such as by giving boys and girls equal access to education; or focus on both hazard and vulnerability, such as by helping a community select its own planning process for new developments. |

| Greenhouse gases | Atmospheric gases that can lead to global warming by permitting the sun’s radiation to reach the earth, but absorbing longer wavelengths which would otherwise be reflected from the earth’s surface, thereby trapping heat in the atmosphere. The main greenhouse gases listed by the IPCC include carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane and ozone. Others mentioned by the IPCC include halocarbons and related molecules, sulphur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons. |

| Hyogo Framework for Action | A voluntary agreement coordinated by the UNISDR (UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction) and signed in 2005 with the tagline ‘Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters’. It was the main international agreement for disaster risk reduction until it expired in 2015. |

| Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) | A UN panel for member governments that assesses the state of climate change science. Reports are agreed by member governments, yielding a governmental consensus on climate change knowledge. |

| Kyoto Protocol | The UNFCCC-linked international and legally binding treaty for setting some limits on greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997, but did not enter into force until 2005 when enough countries had ratified it. Many of the more affluent countries committed to greenhouse gas reductions from 2008-12 with another commitment period from 2013-20. |

| Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) | Eight goals with mainly quantitative targets and indicators that ran from 2000-15 covering poverty, primary education, gender equality, child mortality, maternal health, infectious disease, environmental sustainability and development partnerships. |

| Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) | A mechanism to protect forests from being cut down and to plant trees in places where forests have already been ruined. |

| Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | As successors to the MDGs, the 17 SDGs running from 2015-30 have 169 targets and 304 provisional indicators that target environmental, social and economic aspects of development. |

| Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction | A voluntary agreement coordinated by UNISDR (UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction) and running from 2015-30, succeeding the Hyogo Framework for Action. |

| UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) | A major international climate change treaty, signed in 1992 and entering into force in 1994. Currently, there are 196 parties to the convention comprising mainly sovereign states, but also the European Union and autonomous territories including the Cook Islands. Palestine and the Holy See are observers. |

References

[1] Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030 (UNISDR, 2015)

[2] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org [Insert formal citation when they are published.]

[3] Jessica Mercer Disaster risk reduction or climate change adaptation: Are we reinventing the wheel? (Journal of International Development, 2010)

[4] Karen McNamara and Chris Gibson ‘We do not want to leave our land’: Pacific ambassadors at the United Nations resist the category of ‘climate refugees’ (Geoforum, 2009)

[5] IIan Kelman Difficult decisions: migration from small island developing states under climate change (Earth’s Future, 2015)

[6] Roger McLean and Paul Kench Destruction or persistence of coral atoll islands in the face of 20th and 21st century sea‐level rise? (Climate Change, 2015)

[7] John Tyndall The Bakerian Lecture: on the absorption and radiation of heat by gases and vapours, and on the physical connexion of radiation, absorption, and conduction (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1861)

[8] Study of Critical Environmental Problems Man’s impact on the global environment (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1970)

[9] Study of Man’s Impact on Climate Inadvertent climate modification (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1971)

[10] Klaus Beltzner Living with climatic change: proceedings from the Toronto conference workshop, 17-22 November 1975 (Science Council of Canada, 1976)

[11] Edwin Keitz and Dorothy Berks Living with climatic change phase II: a summary report from a symposium and workshop held by the MITRE Corporation, McLean, Virginia, 9-11 November 1976 (Mitre Corporation, 1977)

[12] Adam C. Martiny and others Strong latitudinal patterns in the elemental ratios of marine plankton and organic matter (Nature Geoscience, 2013)

[13] Thomas Knutson and others Tropical cyclones and climate change (Nature Geoscience, 2010)

[14] Matthias Zahn and Hans von Storch Decreased frequency of North Atlantic polar lows associated with future climate warming (Nature, 2010)

[15] Fifth assessment report (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013-14)

[16] Hanha Dang and others Synergy of adaptation and mitigation strategies in the context of sustainable development: the case of Vietnam (Climate Policy, 2003)

[17] Sally Kane and Jason Shogren Linking adaptation and mitigation in climate change policy (Climatic Change, 2000)

[18] Evan Mills Synergisms between climate change mitigation and adaptation: an insurance perspective (Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2007)

[19] A. Nyong and others The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the African Sahel (Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2007)

[20] Jaboury Ghazoul and others REDD: a reckoning of environment and development implications (Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2010)

[21] World Commission on Dams Dams and development: a new framework for decision-making (Earthscan, 2000)

[22] David Etkin Risk transference and related trends: driving forces towards more mega-disasters (Environmental Hazards, 1999)

[23] Vietnam — 2009 — Typhoons Ketsana and Mirinae (Sheltercasestudies.org, accessed 17 September 2015)

[24] Max Martin A tale of two rivers (Kalvi Kendra, 2011) [link to PDF]

[25] Jonathan Pugh Speaking without voice: participatory planning, acknowledgment, and latent subjectivity in Barbados (Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 2013)

[26] Managing coastal erosion in the Seychelles (YouTube, video published 11 April 2013)

[27] Matthew Boot-Handford and others Carbon capture and storage update (Energy & Environmental Science, 2014)

[28] Jeff Waage and Chris Yap (eds.) Thinking beyond sectors for sustainable development (Ubiquity Press, 2015)