Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[MONTEVIDEO] Paraguayan and Uruguayan scientists are working together to develop a US$1 diagnostic test for syphilis, which they hope could be launched as early as next year.

The early-detection kit for a disease that affects three million people in Latin America would be used alongside pregnancy tests to cut cases of congenital syphilis, say the researchers, who have linked up through the UN University's Biotechnology Programme for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNU-BIOLAC), based in Venezuela.

This programme, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, promotes biotechnology development in the region by providing training and strengthening research, and by working with regional and international scientific and academic organisations.

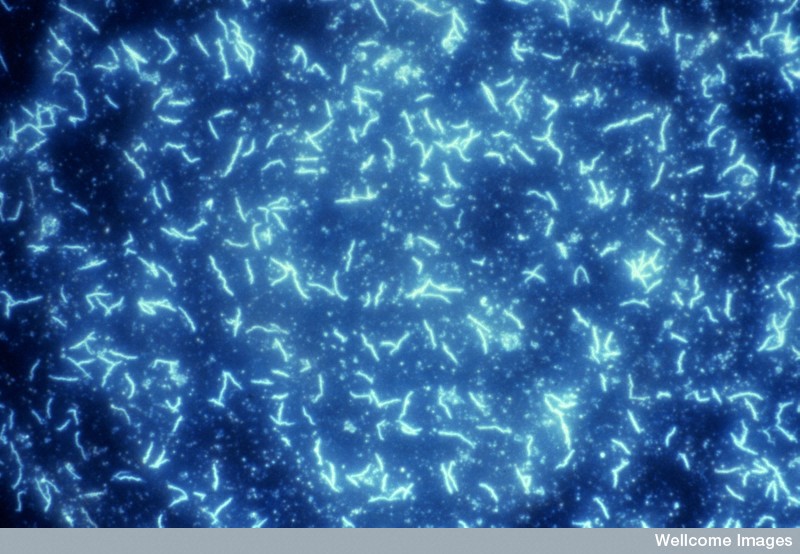

At two UNU-BIOLAC training courses held in Paraguay earlier this year, scientists from Paraguay and Uruguay started to work together to purify proteins from the bacteria that causes syphilis so they can be used for diagnosis with the aim of developing a cheap test for the disease.

“Having a cheap screening test for congenital syphilis will offer great scientific, social and economic value since it will improve health status in general, avoiding future problems related to syphilis.”

Doris Cardona, CES University

Mónica Marín, a biochemistry professor at the University of the Republic of Uruguay, who is involved in the research, says: "In Latin America, syphilis is not concentrated in big cities but is scattered, and it is very important to make a diagnosis and give treatment when patients arrive at a health centre".

"It is much harder to get people to return to check the result of a [test] if they have to travel long distances," she tells SciDev.Net. "The benefit of this test would be direct: once the illness is detected, the patient receives immediate treatment with penicillin, enough to avoid mother-child transmission that happens during labour."

At US$25, current commercial kits for the disease's early detection are too expensive to use for systematic screening, especially when 330,000 pregnant women a year have the disease, yet receive no treatment, resulting in 110,000 babies with congenital syphilis across Latin America.

According to Marín, the plan is to launch the test next year, but the research team needs further funding to do so.

Doris Cardona, an epidemiologist at CES University, Colombia, tells SciDev.Net: "Having a cheap screening test for congenital syphilis will offer great scientific, social and economic value since, as well as reducing the costs of healthcare services, it will improve health status in general, avoiding future problems related to syphilis".

And María De La Calle, head of the perinatal infectious diseases unit at La Paz Hospital, Spain, says: "The idea of using a diagnostic test that is carried out at the same time as a pregnancy test allows early introduction of penicillin treatment, not only preventing congenital syphilis but also first-trimester abortions".

Marín says the UNU courses allowed the researchers to share "experiences, expectations, an overall vision of the topic, problems and possible solutions".

"Partnerships are always beneficial, and when scientists from Latin American countries work together they are sending a message to the international community about the value of regional scientists," says Cardona.

De La Calle adds: "Teamwork is essential when it comes to endemic diseases affecting an entire continent. South-South cooperation will increase efficiency in the early diagnosis of syphilis in pregnancy and it will be the first step to eliminate congenital syphilis in South America."