04/02/20

‘Delhi smog can’t be blamed on Punjab farmers alone’

By: Ranjit Devraj

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NEW DELHI] The extreme smog that shrouds New Delhi in winters is more locally generated than blown in from the wider region around the Indian capital, says a study due to be published March in the journal Sustainable Cities and Society.

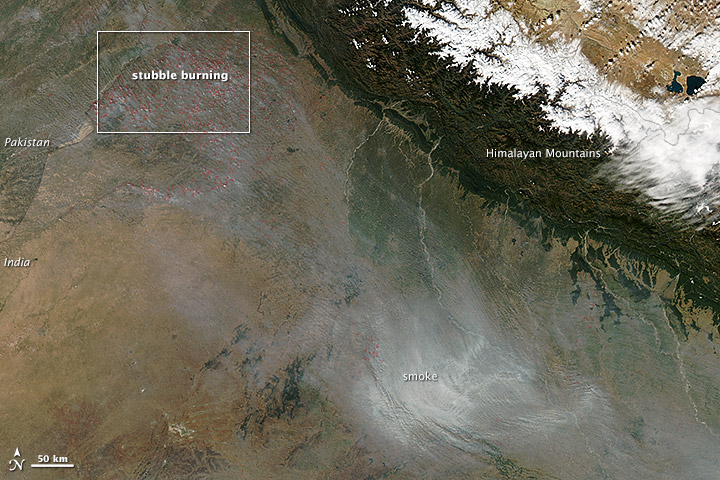

The Air Quality Index in Delhi crosses ‘hazardous’ levels each year between November to February. Last year authorities declared a public emergency and levelled blame at farmers in the neighbouring Punjab and Haryana — India’s granary states — who resort to burning agricultural stubble as a cheap and easy way to clear their fields for winter crop sowing.

“We found that PM2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns) concentrations in Delhi were influenced more by local sources than regional ones,” says Prashant Kumar, study author and founding director of the Global Centre for Clean Air Research at the University of Surrey, UK.

“We found that PM2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns) concentrations in Delhi were influenced more by local sources than regional ones”

Prashant Kumar, University of Surrey

The study looked at the distribution of particulate matter and trace gases (oxides of nitrogen, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and ozone) over a network of 12 air quality monitoring stations in the Delhi-National Capital Region across time and space for the years 2014—2017. It found all air pollutants, barring ozone, are significantly higher during the winter (November to February).

“Sources such as burning crop residue are episodic while concentration of pollutant remains through the year,” Kumar says. “But there is no doubt that plumes from surrounding regions make pollution levels worse during winters.”

He admits though that there are limitations to the study and that new monitoring stations need to be set up to generate more evidence for “apportionment of local versus remotely driven poor air quality in Delhi, especially during episodic conditions such as during winters or crop burning periods”.

However, Kumar says “it is fair to hypothesise that solutions on a local level can go a long way towards improving air quality in one of the most heavily populated areas of India and there is a need for coordination with surrounding regions for effective control of air pollution sources”.

Devinder Sharma, founding member of the Chandigarh-based Kisan Ekta (Farmers’ Unity), a union of 65 farming organisations, says Kumar’s findings are consistent with the facts on the ground. “Crop residue burning in Punjab and Haryana is usually carried out during October and early November after the kharif rice crops are harvested. But Delhi’s smog lasts through the North Indian winter from November to February, so it is clearly unfair to blame farmers alone.”

Delhi’s landscape, weather, energy consumption culture and growing urban population combine to elevate concentrations of air pollutants, says Kumar. “While India’s coastal cities such as Mumbai have a chance to replace smog with relatively unpolluted sea breezes, there are limited avenues for flushing away polluted air in landlocked Delhi.”

“Measures taken so far are inadequate and smack of desperation rather than trying to get to the root of the problem,” Kumar tells SciDev.Net.

Such measures include alternate odd and even license number days for cars allowed on the roads, misting the air with water jets and installing air filter towers in marketplaces. “These are about as effective as cleaning a bucket of water taken out of a big pond,” says Kumar.

Official pollution data for 2018 analysed by the Centre for Science and Environment showed Delhi-wide average concentration of PM2.5 to be 115 micrograms per cubic metre against the national standard of 40 and WHO’s safe limit of 10 micrograms per cubic metre.

WHO estimates air pollution to be responsible for nearly 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2016. In India, around 600,000 deaths are attributed annually to air pollution. Delhi consistently figures among the top ten most polluted cities in the world.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.