By: Athar Parvaiz

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[SRINAGAR] The cashmere shawl that has adorned the shoulders of aristocracy for centuries is made from the downy wool of pashmina goats herded in the high-altitude Ladakh region of India’s Jammu and Kashmir state. But, it takes skilled Kashmiri craftspeople working traditional spinning wheels and looms to turn the wool into the work of art that is the cashmere shawl.

With the annual trade in cashmere shawls now exceeding US$ 752 million, there are new dangers to the art from automated spinning machines and looms that turn out shawls faster than handicraft workers ever can. In order for the automated looms to work on the fine 12-16 microns wool of the pashmina goat, the yarn must be spliced with synthetic fibres.

To protect buyers from being duped with fakes and imitations, the state government of Jammu and Kashmir has stepped in with nanotechnology. This involves inserting nano particles with unique codes into the authentication labels carrying the ‘Kashmir Pashmina’ legend — which has geographical indications (GI) protection under the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement of the WTO.

The main beneficiaries of these measures will be the hardworking craftspeople of Kashmir who have for two millennia been creating a globally coveted product. Currently there are about 150,000 people engaged in the production of handmade shawls in the state.

Experts say that fake pashmina shawl makers add nylon fibre to the wool before spinning and weaving it on machines. “The extremely fine pashmina fibres can never stand machine spinning; that is why they add nylon to them,” Yasir Ahmad Mir, a professor at Srinagar’s Craft Development Institute, tells SciDev.Net. "The traditional Kashmiri spinning wheel and loom, which are completely local innovations, serve as the perfect equipment for spinning and weaving fine pashmina."

Pashmina wool is sheared from a rare breed of goats (Capra hircus) found in the Changthang region of Ladakh, which is more than 4,250 metres above sea level and ideal for herding. The goats produce a double fleece that includes the downy undercoat, or pashmina, and the coarser ‘guard hair,’ that must be removed carefully.

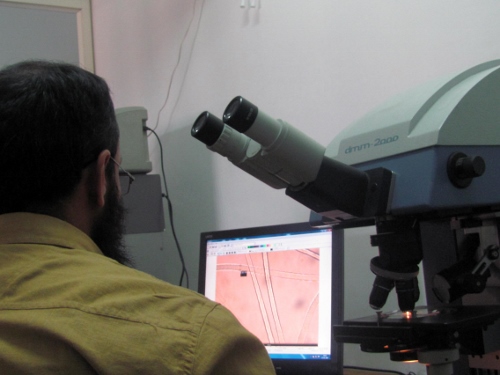

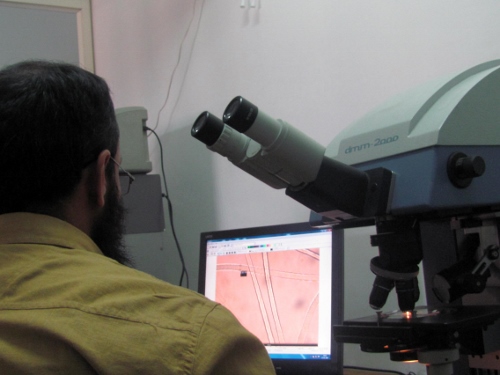

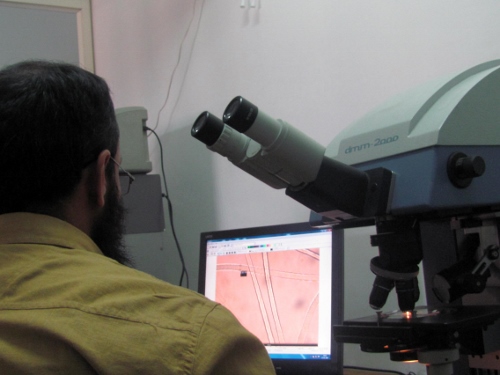

The Kashmir government’s initiatives to protect the interests of herders and craftspeople are best seen at the Pashmina Testing and Quality Certification Centre. Established at a cost of US$ 10 million, the centre has been functional since June.

“Our laboratories determine whether the pashmina wool is hand-spun or machine-spun and whether the shawl has been hand-woven or not,” Younus Farooq, manager of the centre, tells SciDev.Net.

Farooq says that once a shawl passes rigorous tests at the lab, a non-detachable label, which contains details of the product such as its unique number and the name of the artisan, is attached without compromising the aesthetics. A charge of US$ 2.30 is levied on each label.

“After being awarded GI status and setting up the testing laboratory, we are on course to help revive the trade in originals. Now we need to spread awareness among artisans to register themselves as GI-certified traders,” Mir tells SciDev.Net.

Kashmir’s handicrafts director, Gazanfar Ali, tells SciDev.Net that the department plans to launch an extensive advertising campaign “to spread information on how to tell apart genuine and fake pashmina products following the recent steps taken by the state government to maintain the purity and glory of this heritage industry.”

All photographs are by Athar Parvaiz.

This article has been produced by SciDev.Net's South Asia desk.