19/04/21

Leveraging technologies for peace and human rights

By: Melanie Sison

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Big data and ICT are effective tools for peacebuilding and protecting human rights.

[MANILA] In May 2017, a battle broke out in Marawi City, southern Philippines, between government troops and Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL)-affiliated militants. The armed conflict lasted for five months and became known as the Marawi siege, the longest urban battle in the modern history of the country.

In the aftermath of the conflict, International Alert Philippines, a nonprofit, was approached by a group composed of local government personnel and members of prominent families in the city to help monitor the situation and ensure that similar incidents do not happen again.

The group, which evolved into the Early Response Network, now works with the NGO in its peacebuilding efforts, using simple communication technology.

SMS, radio for peacebuilding

International Alert works across the Bangsamoro region, which has a long history of conflict due to land disputes, clan feuds, ethnic and religious tensions, and the presence of militant groups, by combining simple technological tools with community development efforts to build peace.

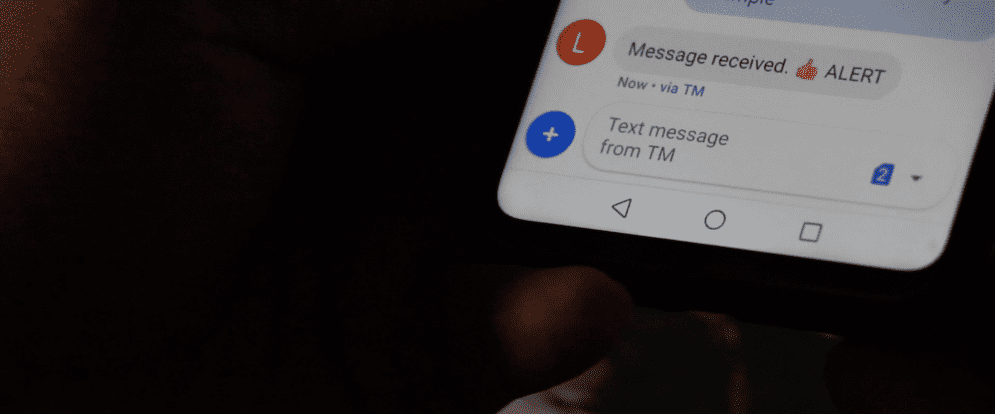

Under the Critical Events Monitoring System (CEMS), radio and texts are used by members of the Early Response Network to transmit real-time information to International Alert. That allows the NGO to monitor incidents and tensions that could lead to conflicts.

Sample message to the Critical Events Monitoring System (CEMS). Image credit: International Alert Philippines.

CEMS bulletins are released to International Alert’s network of representatives from national or local government, disaster risk reduction and management offices, the security sector, international and local NGOs, and community leaders.

Information from CEMS was also used during the COVID-19 lockdowns last year to provide large-format geographic information systems (GIS)-generated technical maps to plan and implement contact tracing and provide relief.

Reports to International Alert through CEMS also alerted them to tension arising from a policy that decreed that all who died from COVID-19 have to be cremated, which went against Islamic belief. Fresh guidelines were then issued to allow special consideration for religious and cultural practices in dealing with human remains.

Two other International Alert systems

International Alert has two other systems that it uses alongside CEMS in its peacebuilding efforts.

Conflict Alert is used by International Alert Philippines as a tool to identify conflict patterns. Image credit: International Alert Philippines.

Conflict Alert, a subnational monitoring system, disaggregates 10-year longitudinal data on violent incidents by consolidating local police, media and community reports that are entered into the system by a pool of encoders. Quality control measures are put in place to screen reports before these are entered in the system. The tool, together with the CEMS, enables International Alert to identify patterns that indicate instability and conflict.

Video credit: International Alert Philippines.

The other system, Resource Use and Management Planning (RUMP), is used in indigenous communities in Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur provinces — areas where conflict over land and identity lead to clan feuds and violent clashes. It also helps local governments and communities identify existing resources and conflict dynamics to address the community’s needs.

Geographic information systems (GIS) are used as a tool in Resource Use and Management Planning (RUMP) to help local governments and communities identify resources. Image credit: International Alert Philippines.

“The main purpose of RUMP is to spur sustainable development in the area but at the same time ensure that investments will not lead to further conflict,” says Nikki de la Rosa, International Alert Philippines country manager. “It’s not just consultations with the people, but also them generating and using spatial data to push forward what they want to happen in their community.”Together, these three platforms generate data that local governments and communities can use in local planning. They also use their analysis to lobby for support from policymakers, national government, and humanitarian organisations, towards peacebuilding.

Video credit: International Alert Philippines.

“Data will only be useful if it enacts change,” says de la Rosa. “Formal and informal mechanisms are needed in response to violence.”

“By using technology and getting people together, we are able to examine the root causes of conflict, come up with concrete solutions and strategies to address these conflicts and work towards the institutionalisation and mainstreaming of these solutions through policy, programmes, and practices at national, local, and community levels,” says Diana Moraleda, senior programme manager for communications at International Alert Philippines.

Working with local communities

Collaboration, however, takes time, especially in areas affected by conflict. Establishing trust and confidence with these communities requires sustained effort.

Amber Houghstow, director of the Center for Environmental Peacebuilding (formerly known as Peace Rising), which is engaged in bridging gaps in predicting and preventing environmental conflict, says technology can be used to empower communities. “Community power can be increased when people not only know what data is being collected about them, but also when they have access to their own data and the tools for analysing and using it.”

“Community power can be increased when people not only know what data is being collected about them, but also when they have access to their own data and the tools for analysing and using it.”

Amber Houghstow, Center for Environmental Peacebuilding

The Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights (CHR) also relies on ICT in its work. Their monitoring tool allows personnel to gather data on internally displaced persons (IDPs) and analyse it against indicators based on human rights and humanitarian standards. “The IDP Monitoring Tool could help in disaggregating data on displacements caused by armed conflict,” CHR says in a statement to SciDev.Net.

Another ICT tool used to monitor human rights issues in the Philippines is the Indigenous Navigator, a civil society initiative that is used to gather relevant information related to Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and data mapping. “Media organisations have also used data mapping techniques in identifying areas where human rights violations related to killings have been occurring,” the CHR statement says.

ICT in peacebuilding

In recent years, organisations have shown that they can produce tools for peacebuilding using big data from different sources. World Food Programme’s HungerMap monitors hunger incidents in “near real-time”. Water, Peace, and Security uses ICTs to monitor water availability vis-à-vis incidents of conflict. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Xinjiang Data Project maps the mass internment camps in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China.

“In the era of social media, mobile phones, and widespread Internet availability, citizens are becoming ‘digital witnesses’, providing important content for conflict monitoring and documenting war crimes, government repression, and human rights abuses,” said a report by the Center on International Cooperation, New York University.

Roudabeh Kishi, director of research and innovation at Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a US nonprofit that conducts disaggregated data collection, analysis and crisis mapping, says that technology can help increase reach even to remote areas.

“While such devices are indeed not accessible necessarily to 100 per cent of the world’s population, their reach is actually quite vast, including to remote areas. Such tools can be useful for sharing information about local security, and can be a useful tool for local populations. And information gathered from such sources can be a useful tool for those collecting conflict data, especially to contribute to peace building,” Kishi says.

Issues and risks

The use of ICT has certain downsides.

Developing countries like the Philippines may be at a disadvantage because of budgetary constraints and limited access to technologies. The country ranks 19 out of 26 nations in Asia in the Inclusive Internet Index, indicating low affordability of smartphones and mobile data and poor Internet connection.

Data literacy is also a problem, with a limited number of data science experts who can effectively generate and analyse data relevant to peacebuilding and human rights. Houghstow suggests tapping public-private partnerships to help remedy this.

However, data collection in remote conflict zones can be challenging, says CHR, citing fear of reprisal or attacks when visiting these areas.

Accidental or deliberate data breaches are a serious issue, especially given the sensitive information handled by peacebuilders. Peacebuilders who use IT tools also have to be careful not only about the information they disclose, given the multi-layered issues facing conflict areas. De la Rosa says that the maps used in RUMP are not made publicly available because these could be used to support contentious land ownership claims.

Kishi warns that the use of ‘big data’ in conflict monitoring is not necessarily reliable. “Automation can result in ‘false positives’ — i.e. a news story that has nothing to do with conflict. Or can result in duplication — i.e. multiple media outlets reporting news on the same event, making it seem as if numerous events happened when in reality only one event happened.”

She also notes that automated systems tend to only aggregate news in English, leading to “a bias towards the type of news reported in international media, such as larger, more lethal events”.

Houghstow says that certain databases may not include data on specific instances of conflict and violence, such as state-sanctioned violence, police brutality, oppression, and violence against women. “Data isn’t neutral,” says Houghstow.

Another risk is the misuse of technology. Extremist groups are known to spread their ideologies through social media to radicalise young people. While online platforms respond to this threat by banning questionable content and those posting it, research from Nature shows that these efforts are largely ineffective. Disinformation, misinformation, and fake news, meanwhile, have become buzzwords as the Internet gets populated with political propaganda.

“We have to understand that state apparatuses have unequal access to data and technology and have an advantage in using it to their ends,” says Houghstow. “Data and ICT access can be used to build community power as well as state power.”

The Center on International Cooperation* report noted that there is “considerable distrust” among the general population on the use of these technological innovations. “This distrust comes from concerns about technologies being used for mass surveillance, creating massive unemployment, being used for autonomous weapons, or enabling cyberattacks.”

Technology is neither good or bad on its own, says dela Rosa. “For us, technology is neutral. It depends on the people or organisation using it. It depends on the sensitivity of the people using it.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.

*This article was edited on 22 April 2021 to correct the name of the Center on International Cooperation.