By: Zhen Yue

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[KUALA LUMPUR] Scientists have obtained a compound with antiviral properties from marine bacteria found off the coast of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea.

The compound — antimycin A1a — displayed potent activity against a range of viruses, including the western equine encephalitis virus and RNA viruses from the Togaviridae family, according to the research results published in PLOS ONE last month (5 December).

There are about 30 ‘alphaviruses’ in the Togaviridae family that cause “significant diseases” in humans and animals all over the world, the study says. Encephalitic alphaviruses can kill up to 70 per cent of people they infect and leave most survivors with long-term neurological damage.

In their paper, the researchers note there are currently no licensed vaccines or antiviral drugs for alphavirus infections, resulting in a “pressing need” to identify new antiviral compounds.

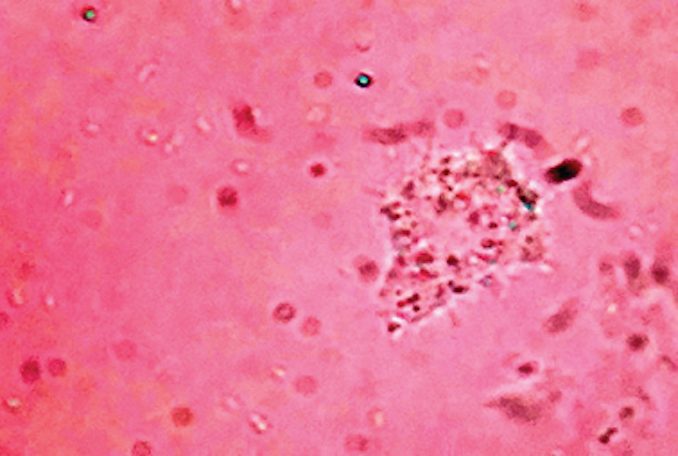

The isolated compound is generated by a novel marine bacteria Streptomyces kaviengensis. In addition to displaying antiviral properties when tested on cultured cells, the compound was also able to reduce disease severity and enable the survival of some mice that had been infected with what is normally a lethal dose of western equine encephalitis virus, the paper says.

The study received funding support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is part of the United States’ National Institutes of Health.

Principal investigator David Miller says the concept behind the research was to use the “ability of microorganisms to produce compounds of incredible and nearly limitless complexity” in the search for new drugs to treat viral infections similar to the way that many current antibiotics treat a wide range of infections.

Fatimah Md Yusoff, head of the Institute of Bioscience Laboratory of Marine Biotechnology at Putra University Malaysia, agrees that marine products offer great potential for drug discoveries.

“Marine natural products derived from plants — seaweeds, sea grasses and microalgae — and animals, especially invertebrates, fishes and microorganisms, have the potential to provide a vast array of chemical structures to be explored and discovered,” she says. “These marine resources have great potential for antiviral drug development. But more studies are needed to understand not only their structure and effects, but also their effective antiviral application in humans.”

Although antimycin A1a has shown antiviral activity in current tests, Miller was unable to give a timeline for drug development. He says the process takes years and is never certain.

“There are many steps involved and failure could occur at any of them,” he says.

Link to full paper in PLOS ONE