05/12/19

Loudspeakers used to attract fish back to dying coral reefs

By: Claudia Caruana

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NEW YORK] Marine life researchers from the UK and Australia are using the sounds of healthy sea life to attract fish and plankton, hoping to get them to help revive dying swaths of the Great Barrier Reef.

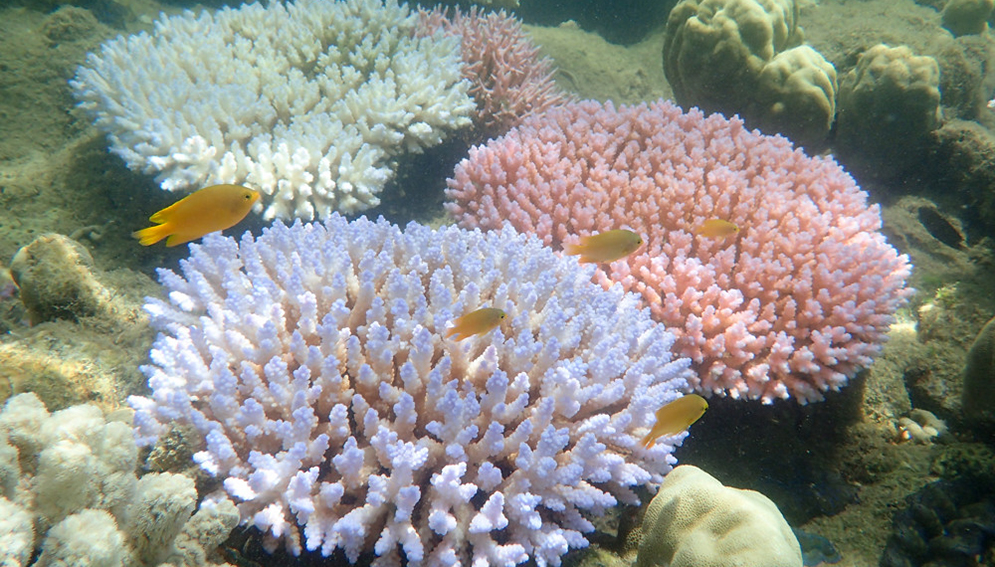

Half of the Great Barrier Reef, the largest reef system in the world, suffered catastrophic damage in a 2016 heat wave, followed by bleaching the next year. Coral reefs, on which 25 per cent of the world’s fish species depend at some stage in their life-cycles, are similarly threatened by warming and acidification of the seas as result of climate change.

The study, published by the researchers on 29 November in Nature Communications, found that broadcasting healthy reef sounds using underwater loudspeakers can double the total number of fish arriving onto experimental patches of reef habitat as well as increasing the number of species by 50 per cent.

“We tracked the effects of our sound playback for 40 days. That was enough time to show major increases in the number of fish and the diversity of species returning, and that these were staying beyond an initial period”

Andrew Radford, University of Bristol

Andrew Radford, professor in The School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, and one of the authors of the study, says: “We have known for a long time that many organisms use acoustic cues from reefs when finding their way back from the open ocean early in life. Those acoustic cues arise from many sources, not least the animals living on reefs.”

Coral reefs became degraded due to warming seas, and those degraded reefs contain many dead corals and far fewer inhabitants. “Last year, we showed that those degraded reefs sound quieter and different than healthy reefs; crucially, we also showed with field experiments that the sounds of degraded reefs are less attractive to young fish than are the sounds of healthy reefs,” Radford says.

He adds: “We tracked the effects of our sound playback for 40 days. That was enough time to show major increases in the number of fish and the diversity of species returning, and that these were staying beyond an initial period.”

Future work, Radford says, would ideally track the effects for much longer so that measures of individual survival and reproduction, as well as community structure, could be determined.

“The idea behind ‘acoustic enrichment’ is that this can help kick-start coral reef recovery. Once fish start returning, they will start generating a healthier soundscape, which should, in turn, result in further recruitment of fish,” says Radford. He does not think it necessarily to have the loudspeakers present long-term, though this would have to be tested.

Radford, however, cautions that just bringing fish back to degraded reefs will not reverse the degradation seen on many coral reefs. “It is a promising technique for management on a local basis but needs to be combined with habitat restoration and other conservation measures; rebuilding fish communities with the help of playbacks might accelerate ecosystem recovery but is not enough alone.”

Another study author, Mark Meekan, senior principal research scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, says he and co-researchers have been looking at the role of sound in the lives of reef fish since the early 2000s.

“Initially, we examined how young fish used sound to navigate back to reefs after dispersal in the plankton. We then looked at how anthropogenic noise (the sound of boats) disrupted critical fish behaviour such as defensive reactions to predators. This most recent work builds on these studies.”

“The idea would be to use acoustic enrichment just during the season when small fish arrive on reefs, not indefinitely. It might only need to be done in in this season over a couple of years, until enough small fish have settled,” says Meekan. “Showing that acoustic enrichment makes a difference in coral regrowth is a key step that we are now focusing on.”

Maud C.O. Ferrari, professor, aquatic predation and environmental change in the departments of vet biomedical sciences and biology, University of Saskatoon, Canada, says the study “shows the value of innovative thinking when it comes to the enormous problems faced by coral reefs.”“Although it’s not likely that we could use speakers broadcasting noise on a very large scale to help reefs recover, this idea could be useful to maintain at least some smaller patches of reef in good condition. These could act as ‘arks’ for the remainder, giving humanity some time to catch up with our efforts to reign in carbon emissions and stabilise the world’s climate,” Ferrari says.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.