By: Saleem Shaikh

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[ISLAMABAD] Agricultural scientists say that observing a ‘wheat holiday’, or the growing of alternative crops, may be the best way for Bangladeshi farmers to fight the ‘wheat blast disease’ that first appeared in the country in 2016 and threatens to spread to neighbouring South Asian countries.

Wheat output in key farmlands of southwestern Bangladesh has already been reduced by half, according to a study published by scientists this month (March) in Land Use Policy. Wheat is Bangladesh’s second most important staple after rice, and South Asians consume an estimated 100 million tonnes of wheat annually.

“Implementing the proposed wheat holiday plan for a few years is the most workable solution to avoid damage to the country’s food security and possible economic losses from wheat blast disease attacks”

Khondoker Abdul Mottaleb, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

As a precaution, India has ordered a three-year wheat holiday, starting 2017, in the Murshidabad and Nadia districts of West Bengal state, adjoining Bangladesh. Wheat cultivation within five kilometres of the long Indo-Bangladesh border has also been banned by India, which produces more than 98 million tonnes annually.

According to the study carried out by scientists from Bangladesh and Mexico, growing alternate crops such as maize, lentils and onion on wheat lands may be the only way to prevent spread of the Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype triticum fungus since no effective fungicide or resistant crop variety exists. Of the 437,000 hectares under wheat in Bangladesh, 280,000 hectares are now vulnerable to blast disease, the researchers say.

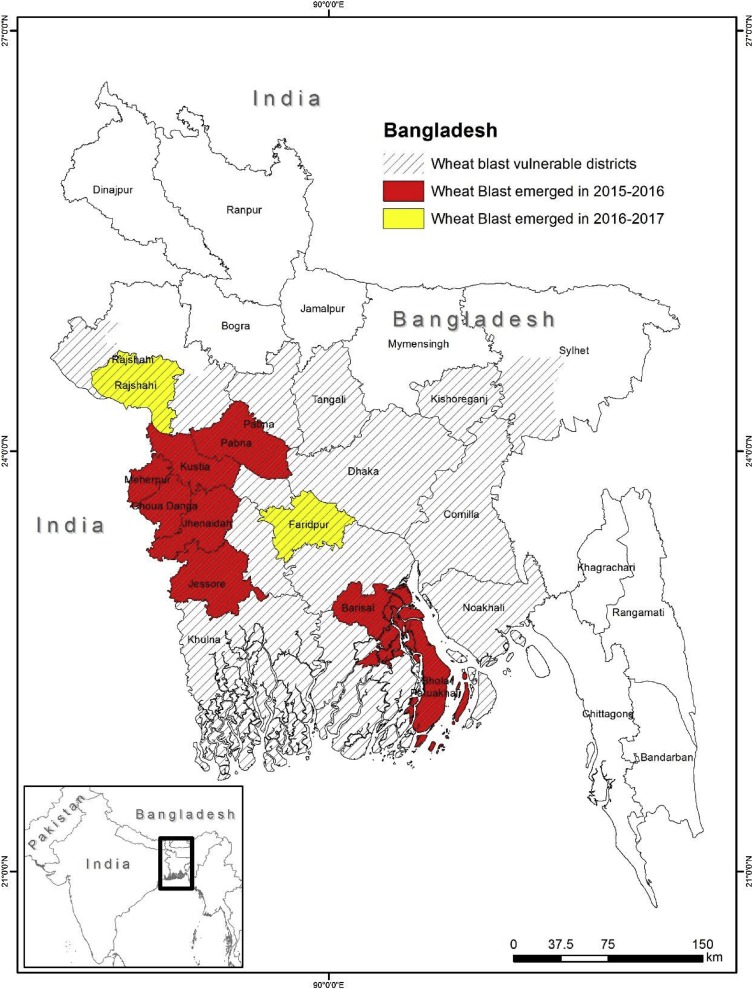

The Bangladesh districts affected by the wheat blast, as well as the districts vulnerable to the blast (Image credit: ScienceDirect)

“Implementing the proposed wheat holiday plan for a few years is the most workable solution to avoid damage to the country’s food security and possible economic losses from wheat blast disease attacks,” says Khondoker Abdul Mottaleb, an author of the study and agricultural economist at the Mexico-based International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center.

After M. oryzae triticum first surfaced in Brazil in 1985 it spread rapidly throughout South America. By the early 1990s, the fungus had laid waste some three million hectares of wheat farms and affected the potential of the continent’s fertile savanna lands as a wheat producing area. According to the study, wheat blast is now an established crop disease in Bangladesh and is spreading fast.

Mottaleb suggests that the wheat holiday plan be first introduced in the ten currently affected districts and then extended to the entire country.

The 2016 outbreak affected the Barishal, Bhola, Chuadanga, Jashore, Jhenaidah, Kusthia, Meherpur and Pabna districts where wheat yield dropped by up to 51 per cent, the study says. A second attack, the following year, saw the fungus spreading to the Faridpur and Rajshahi districts.

Naresh Chandra Deb Barma, director-general, wheat and maize research institute at the Bangladesh Agriculture Research Institute, Gazipur, says that continuing with wheat cultivation is risky for farmers and the wheat holiday plan is the only viable remedy to prevent its spread.“We are already persuading wheat farmers in the affected and vulnerable districts through extension and awareness programmes to discontinue wheat cultivation for at least three years and cultivate economically viable alternative crops to rid the country of the deadly wheat disease,” Barma tells SciDev.Net.

The researchers, however, caution against a permanent wheat holiday as that could affect food security and increase the country’s wheat import bill.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.