09/06/20

South-East Asian schools reopen to the ‘new normal’

By: Fatima Arkin

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

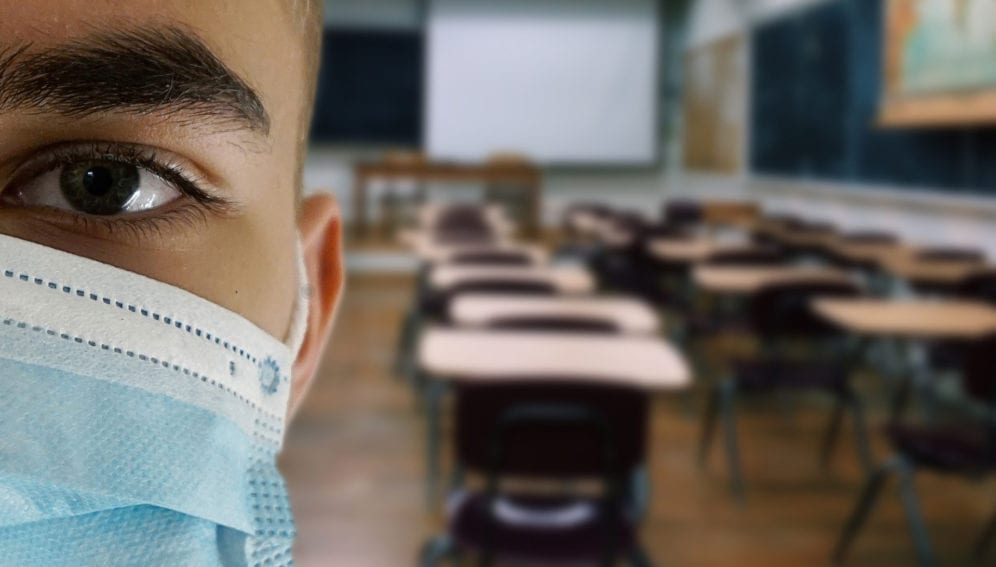

[MANILA] As South-East Asian countries cautiously plan and start reopening schools following COVID-19 lockdowns, the ‘new normal’ of education requires that public health protocols are respected and educational policies continuously revised to ensure that no student misses out on education.

The South-East Asian region has recorded 104,000 COVID-19 cases and at least 3,000 deaths from the virus, though the pattern of disease-spread and containment strategies have differed widely. Singapore leads in cases with 38,300 but only 25 deaths while Indonesia, with 32,000 cases, leads in deaths, with nearly 1,900. The Philippines has seen over 22,000 COVID-19 cases and 1,000 deaths.

“Even within a sub-region there will be a diversity of experiences in education — between countries and, alongside, diversity within any one country,” Jenelle Babb, team leader on education for health and wellbeing at UNESCO in Bangkok, tells SciDev.Net.

“Even within a sub-region there will be a diversity of experiences in education — between countries and, alongside, diversity within any one country”

Jenelle Babb, UNESCO

Just how vulnerable children are to COVID-19 is still unclear, but several scientific studies suggest that kids are less likely than adults to become seriously infected or pass it on to others.

“The risk of COVID-19 in children does not seem to be particularly serious compared to the risk of other viral infections in typical flu seasons,” Ben Cowling, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the University of Hong Kong, tells SciDev.Net. “We don’t usually close schools during flu seasons.”

Partly motivated by such information, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and other countries in the region have already started to re-open schools, or plan to do so soon.

The topic has ignited debate in the Philippines where the country’s Department of Education has announced that classes for basic education will commence on 24 August while Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is adamant about not letting that happen until a vaccine is developed.

School closures are adversely affecting the developing world. A May 2020 UNDP report estimates that the “effective out-of-school rate” for primary school education — meaning the percentage of primary school-age children without Internet access and hence with no continuing educational activities — is 86 per cent in countries with low human development indices (HDI) compared to 20 per cent in countries with very high HDI.

“Overall, this is the largest reversal of this indicator in history, opening new gaps in human development,” notes the report. “Being out of school — even for a limited amount of time — is expected to have long-term impacts on learning, earning potential and well-being.”

In the longer term, as things start to normalise and as stakeholders begin to take stock of the impact of COVID-19 on education, what should become the new normal as part of educational planning and budgeting is increased readiness for crisis response, says Babb. “One in which the needs of the most vulnerable are anticipated with strategies and systems in place to deliver in response to those education needs.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.