By: Saleem Shaikh

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

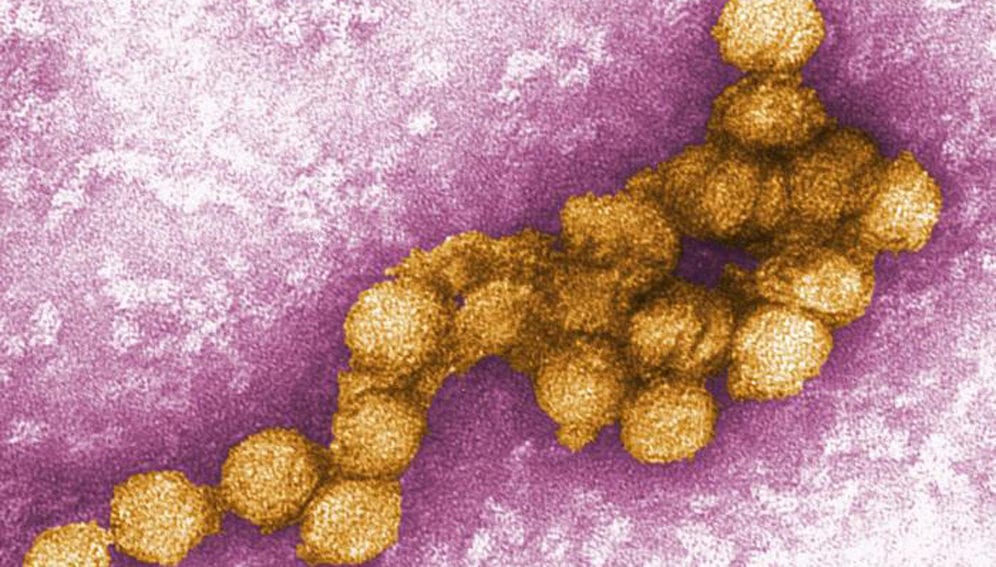

[ISLAMABAD] Researchers who detected the West Nile Virus (WNV) in the blood of donors in Pakistan are calling for urgent, coordinated surveillance to assess the distribution in the country of the virus known to cause deadly neurological disease.

Spread by mosquitoes, WNV infection is generally asymptomatic. But in about 20 per cent of cases, fever, headache and vomiting develop; less than one per cent of these cases lead to potentially fatal neurological complications. The virus causes inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or inflammation of the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (meningitis), studies show.

The researchers published their findings online this month (January) in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. For their study, they analysed 1,070 serum samples drawn from blood donors in the Punjab province from 2016 to 2018 and found samples of the virus. In contrast, researchers screened 4,500 mosquito specimens collected from 2016 to 2017 from five selected districts of Punjab province and these were found negative for WNV.

“Transmission through human blood transfusion poses grave risks.”

Muhammad Saqib, University of Faisalabad

Muhammad Saqib, assistant professor at the University of Faisalabad, Pakistan and one of the authors of the study, tells SciDev.Net that while traditionally the mosquito bite is the primary cause of WNV infection, blood transfusion is an important mode of transmission in Pakistan. “Transmission through human blood transfusion poses grave risks,” he says.

Saqib and his fellow researchers, drawn from Pakistan and China, warn that Pakistanis will be increasingly vulnerable to WNV infection unless surveillance, screening and reporting facilities are immediately put in place.

Since the 1990s, WNV infections and related outbreaks of neurological disease have grown to become increasingly serious public health problems. Genetic analyses have identified multiple lineages, but most studies have focused on ‘Lineage-1’. This particular lineage first emerged in 1999 in New York and has a propensity to cause neuro-invasive disease.

“Comparison of partial sequences of WNV with a global representation of 23 WNV sequences have revealed that the strains present in Pakistan belong to the WNV Lineage-I,” Saqib says.

The Pakistani WNV strain sequences grouped into Lineage-I are the foremost causes of outbreaks in such countries as Australia, India, Russia and the US, apart from Europe and the Middle East. Also, nucleotide sequences from Pakistani strains are 98 to 99 per cent similar to isolates of mosquito origin from the Xinjiang province of China, the study finds.

Khan said her department is collaborating with the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogens Institute to introduce by mid-year a nation-wide WNV surveillance, detection and reporting system. “These efforts aim to map out disease distribution, develop diagnostic and reporting facilities at national and provincial levels and come up with suggestions for the government.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.