06/01/20

Urban agriculture — the future of farming

By: Paul Teng

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Technology can help urban agriculture meet the food security requirements of the future, says Paul Teng.

According to UN-Habitat, the UN agency for human settlements, the 21st century will be the century of urbanisation. The year 2008 saw, for the first time in history, the world’s urban population overtake its rural population.

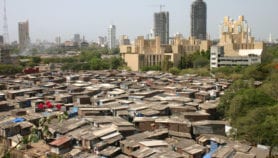

As the world becomes increasingly urban, food demand will come mainly from people living in cities, while there will be fewer rural farmers producing food on less land with less water. Furthermore, the locus of poverty is likely to shift from rural to urban areas. Urban and peri-urban areas can and will have to play a bigger role in food security. But to accomplish this requires supportive enablers such as new farming approaches and technologies, new thinking and policies by policymakers, politicians and consumers willing to accept new food types and unconventional ways of food production.

With global food demand estimated to increase by at least 50 per cent by 2050, it is necessary to ask what and where else can be tapped to produce the quantum of food needed.

“Urban centres should strive to become food producers, and not just consumers”

Paul Teng

Several years ago (2014), this author asked, with respect to food security, whether cities should be part of the solution and not just be viewed as the problem [1]. Much progress has been made since in affirming the contribution of cities to growing food close to where it is needed. Urban farming, especially in community gardens, has further helped improve the nutrition quality of inner city diets, an aspect of food security causing grave concern with the rise in non-communicable diseases.

A traditional rural responsibility

Traditionally, the practice of agriculture has been considered a rural phenomenon.

However, with more people now living in urban areas, food insecurity has become an urban phenomenon. Urban centres should strive to become food producers, and not just consumers. Urban agriculture can help cities achieve a high level of self-sufficiency in at least some of the key food products that its inhabitants consume.

Urban agriculture is considered as the growing of plants and the raising of animals within and immediately around cities. It is estimated to currently contribute 5 – 20 per cent of the world’s food needs [2].

The most striking feature of urban and peri-urban areas, which distinguishes it from rural agriculture, is that it is integrated into the urban economic and ecological system. Urban agriculture is embedded in — and interacts with — the urban ecosystem and its resources. Such linkages include the use of urban residents as labourers and the use of typical urban resources (like organic waste as compost and urban wastewater for irrigation), direct links with urban consumers, direct impacts on urban ecology (positive and negative), competing for land with other urban functions, being influenced by urban policies and plans, etc.

About 800 million people are now involved in urban agriculture and contribute to feeding urban residents. Most of these people are from the developing countries of Asia and Africa. Of these, 200 million produce for the market and 150 million work full-time [3]. Urban agriculture activities range from relatively low-tech community gardens and small farms using conventional techniques, to highly sophisticated plant factories (with enclosed environments and artificial light) and bioreactors producing cell masses. Urban farms can contribute to rehabilitation of communities suffering from economic dislocation, and to providing an alternative use of the consequential abandoned land.

Urban agriculture in developed countries has seen significant growth in recent years thanks to high value-added agriculture, the promotion of the ‘garden city’ concept, expansion of community gardens and roof-top planting and use of urban agriculture to promote environmental sustainability. Contamination from particulate air pollutants has so far not been an issue in the cities concerned because of chosen locations or exclusion technology such as “plant factories”. In modern cities like New York and Singapore, urban agriculture is seen as an application of high technology (especially digital, mechanical) backed by rigorous science to create new food supplies and employment.

Urban agriculture in developing countries is less pronounced but has great potential for growth. The success of urban agriculture in cities such as Hanoi, Shanghai, Beijing, Mexico City and Dakar has shown how urban farming can contribute to poverty reduction, food security, improvements in nutrition, increased income, environmental protection and increased awareness of the importance of agriculture through on-site agro education. In these cities, the Resource Centres on Urban Agriculture and Food Security Foundation, Netherlands, has estimated that up to 80 per cent of fresh vegetables may come from a city such as Hanoi and immediate periphery.

Exciting new approaches and technologies

Agriculture in the 21st century is strongly influenced by new scientific tools (molecular markers, gene editing, etc.) and new technologies (digital, mechanical, biological) which have resulted in a set of powerful technology outcomes with applications in rural and urban situations. In a previous SciDev.Net article [4], I listed some:

- Agronomy and agricultural biotechnology to innovate inputs for crop and animal agriculture such as seeds, pest control, seeds with new genetics, microbiome and animal health

- Mechanisation, robotics and equipment such as on-farm machinery, automation, drones guided by GPS or GIS systems, environmental sensors, and growing equipment

- Farm management software, Internet of Things systems with sensing and intervening – these include environmental, farming data capture devices, decision support software, big data analytics and miniaturised portable applications

- Novel farming systems such as indoor farms, plant factories with controlled environment, aquaculture systems, and grow-out facilities for insects, algae and microbes

These technologies have been used separately or in combination to farm in open spaces, shaded shelters and completely controlled environments. Environment sensors for temperature and moisture have been deployed by urban farmers in open fields or shaded farms for many years, often accompanied by computer software which perform analytics and provide advisories.

One of the most ‘Disruptive Technologies’ in urban farming is the ‘Plant Factories with Artificial Lighting’ or PFALs which grow vegetables in trays vertically stacked within a room in which the environment (air, light, temperature, and humidity) is controlled to provide optimal plant growth.

LED lighting is used to optimise the plants’ photosynthetic capacity for vegetable growth and development and reportedly have shortened time-to-harvest by almost a third. The company NewBean Capital, Singapore, estimated that there were over 450 PFALs in commercial production in Asia in 2016, mainly located in China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea. The PFALS produce more kilograms of vegetables per unit area and use less water, although energy efficiency is still to be improved. But their unique proposition is that vegetables can be grown year-round and for the longer term can buffer against climate change.

On the horizon for urban food production is the use of cell culture technology to produce vegetable products and even animal meat (colloquially referred to as ‘clean meat’) in large bioreactors housed indoors. This author participated in the first International Plant Cell Technology Industry Summit in October 2019 in Chongqing, China, and witnessed the government’s investments to establish this as a viable industry to produce food ingredients and actual consumable food.

Part of food future

With more and more people living in urban areas, the international community needs to consider urban food security and the role of urban agriculture in its own right but still recognise its strong inter-relationships to the wider discourse on food security and to the global food supply chain.

While there continues to be a strong interdependence between urban and rural areas, the urban dimensions of food production merit distinct attention and focus from national governments. In order to successfully address the growing problem of urban food security in the face of food price increases, policies and programmes need to better reflect the urban context.

Appropriate support mechanisms such as political, legal, operational and regulatory frameworks need to be put in place to facilitate urban agricultural activities, move them into the formal economy, and address food safety and health concerns. Related to the latter two is the issue of food waste and recycling this into circular food systems which support sustainability approaches.

Urban agriculture as an integral socio-economic activity provides many lessons for similar geographies such as small island states, of which there are many in the Caribbean and Pacific regions of the world.

The world will need much more food in 2050 that is produced using sustainable practices under huge climate change challenges. The traditional countryside is not enough and spaces in cities need to be tapped to ensure food and nutrition security for all. Urban agriculture is coming to age as a serious activity to complement food production in the countryside and is like to become even more important as technology advances and climate variability forces more farming in controlled environments.

Professor Paul S. Teng serves as Adjunct Senior Fellow (Food Security) in the Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies (NTS Centre) at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore, while serving also as Dean and Managing Director of the National Institute of Education International Pte Ltd (“NIE International”) at NTU.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.

References

[1] https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/nts/1804-food-security-cities-as-part/#.XfXR8XlPohc

[2] Prem Nath (2015) Agriculture and Food Technology in Human Life, Chapter IV. India: Scientific Publishers.

[3] Escaler, M. and P.S. Teng. 2014. Urban Food Security and Urban Agriculture in Asia: Cities as Part of the Solution. In The Politics of Food Security: Asian and Middle Eastern Strategies (Edtd. Sara Bazoobandi), pp. 159-178. Berlin: Gerlach Press.

[4] https://www.scidev.net/asia-pacific/agriculture/opinion/disruptive-technologies-transform-asian-agriculture.html