By: George Achia

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[BUJUMBURA] Eight years after the civil war in Burundi, the tiny eastern Africa country is charting a new path in rebuilding a research and development agenda.

Like many others, Hatunyumubama Gilbert fled the country to Belgium when the second phase of the war began in 1993, pitting the Tutsi minority against the Hutu majority. In Belgium, he took up a doctoral degree in livestock production. The war raged until 2005.

Even when he finished studying, Gilbert was unsure about returning home to continue his research ― he was still smarting from the effects of the war, as were many other Burundi scientists in the diaspora.

"Most scientists who had fled were afraid for their families' security and were not sure about their future economic situation in the country that was being ravaged by the war," says Gilbert, now head of animal production at the University of Burundi.

But Gilbert is among a few scientists who have come back. He and colleagues are now steering a research and development agenda devastated by the many years of conflict.

The war, he says, led to massive brain drain with many researchers going to foreign countries. Some opted to go and teach in the then relatively peaceful Rwandan universities, where they also got better terms of service.

No easy return

Life has not been easy for those who have chosen to return.

"Since I came back two years ago, the Burundian University leadership is facing challenges related to lack of qualified professors and researchers. This forces Burundian lecturers and professors to spend more time teaching rather than engage in scientific research, a situation compounded by the lack of funds," he tells SciDev.Net.

"Universities have limited financial support to help students and researchers to carry out scientific research," he adds.

Public universities are funded by the government and donors like Belgium Technical Cooperation. During the civil war, most donor supported research projects were halted when donors suspended bilateral cooperation.

Plans are in place

Gilbert, now a senior professor of livestock production and management, says this led to a 90 per cent fall in scientific publications.

To reverse this situation, the minister of higher education and scientific research decided last year to entice professors back — by increasing initial salary eight times over.

Gilbert says that before the move, full professors were paid 500,000 Burundi Francs (around US$310), but now they earn four million Burundi Francs (around US$2,500) a month.

"The number of local lecturers and professors is increasing. The university is positioning itself to be competitive and search for more donors to fund research activities," says Gilbert.

"At the faculty of agriculture at the University of Burundi, between 12 to 15 doctoral lecturers have come back," he adds.

Seven, he says, came back specifically because of the salary increase.

"The researchers are being encouraged to teach full-time or part-time, and there has been some success in enticing back Burundian academics in Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and USA through the salary increment initiative," says Tatien Masharabu, the director general of the Directorate for Science, Technology and Research in the ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, adding that policy has been put in place after the war to promote research and development.

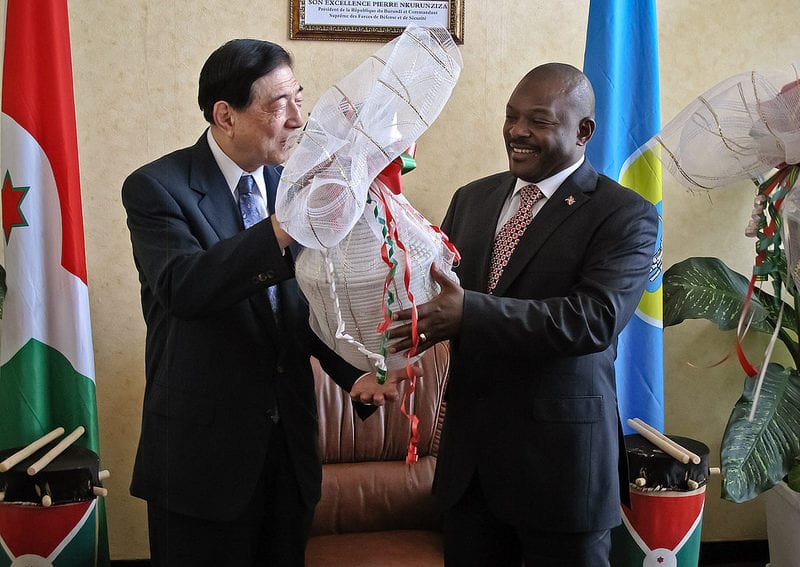

Masharabu explains that the Higher Education Act, which was signed by President Pierre Nkurunziza in December 2011, led to the establishment of the Directorate in April 2012, which in turn leads in planning and implementing national policy on science, technology and innovation.

"The Higher Education Act is meant to regulate and breathe life into a declining education system and research and development in the country. The law outlines the functioning of public and private universities, the creation and approval of courses, accreditation of training programmes and the requirements of higher education institutions such as libraries and laboratories," says Masharabu.

He says the Directorate is developing a ten-year action plan to promote both human and infrastructure research capacity through a national policy for scientific research and technological innovation — expected to kick off later in the year.

"Developing a research framework is in progress but the document which will highlight the priorities areas and time planning is not yet ready but under review," he says.

Nevertheless, the priorities are expected to include agriculture and food security, medical technology, water, energy, biotechnology, engineering and use of local knowledge.

Masharabu adds that a national council for science, technology and innovation is to be set up this year.

Rebuilding agriculture

Masharabu says Burundi still struggles to find enough expertise to implement its science policy: there are too few staff members at the ministry and inadequate facilities are other key challenges.

Nevertheless, Burundi's research and development sector is slowly but surely picking up.

Now, Gilbert and his team from the faculty of agriculture at the university have started raising funds to rebuild research centres that dealt with small ruminant and domestic livestock. Most centres were destroyed, and their animals stolen, during ethnic fighting.

"I had four research centres spread across the country. Currently, no centre operates because the infrastructure was destroyed," Gilbert tells SciDev.Net.

He is now drafting a proposal to apply for development cooperation funds in Belgium and expects funds by next year to rebuild the centres.

The agricultural sector was one of those worst affected, as most research facilities were burnt down. Neither Gilbert's faculty of agriculture at the university, nor the Institute of Science and Agronomics of Burundi (ISABU), has been able to effectively research agricultural challenges such as the many crop and livestock diseases facing Burundi.

"Cassava, a key staple food for many Burundians, has been under attack from cassava mosaic disease since 2002, and no research efforts on resistant varieties has been done to address this, due to lack of facilities and funds," he says.

Nkurunziza Gelase, a researcher at ISABU, says the institute lost access to seven research centres spread across the country.

Gelase, who breeds maize at ISABU, says that some maize varieties like the hybrid Kitale, were lost during the war, affecting food production and security across the country.

ISABU is now testing high-yielding hybrid seeds that are fast maturing and resistant to maize streak virus. They could be released in September to help Burundian farmers boost the country's food security.

Support from Belgium

Because of agriculture's role in Burundi's economy — as a major source of employment and through its importance for food security — international donors and agencies are helping rebuild agricultural research in the country.

For instance, Belgium Technical Cooperation is supporting a programme, institutional and operational support programme for the agricultural sector (the PAIOSA programme) with a research component based at ISABU, and also supporting researchers at the university.

"After the war, we are now improving research especially in agriculture, by rebuilding and innovating destroyed research facilities. We are looking on how to reorient the research agenda based on community's needs," says Valerie Claes, the international technical assistant for PAIOSA.

The project which started in December 2012 and ends in 2017 through Burundi-Belgium cooperation seeks to rebuild both ISABU's human capacity and its research facilities at the institution.

This includes buying new research equipment for the organisation and putting up new laboratories, as well as by introducing new proactive management practices.

"Within the agricultural research and development component of the project, we also have the competitive research fund of US$220,000, meant for the ISABU researchers to come up with innovative research ideas that could be funded to address the national agricultural research priorities," Claes tells SciDev.Net.

So, despite the past conflict and economic turmoil, the future of the research and development sector is looking promising.

This article has been produced by SciDev.Net's Sub-Saharan Africa desk.