By: Jamie Drummond

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Even though aid alone can‘t solve all Africa’s problems, it underpins a burgeoning number of success stories, argues DATA‘s Jamie Drummond.

A small but articulate group of critics has been stealing headlines by attacking aid and undermining the Millennium Development Goals.

William Easterly fired the most recent shot with a demand for a "rethink of grand aid plans" (see Time for a grand re-think of grand aid plans). He cites Africa as a continent flooded with development assistance but with little to show for it.

Timeframes are important in this debate. Anti-aid advocates usually highlight the billions spent by Western governments over the past four or five decades, especially in Africa. They ignore distortions introduced by Cold War politics, when aid was misused to prop up dictators rather than improve the lives of the poor, and new assistance models, especially in education and health, that are delivering good results. It is these programmes that should be scaled up because, by and large, they work.

Sub-Saharan Africa is where the Africa advocacy group DATA (Debt AIDS Trade Africa) concentrates its efforts and where the battle against stereotypes is hardest. Images of poverty and war that dominate Western media make arguments about aid failure all the more believable. In fact, the number of countries at war in Africa is down from 16 in 2002 to five now. From three elected democracies in 1989, by 2005 there were 18. Of the 20 countries experiencing economic growth rates of five per cent or more, 17 have averaged this rate for a decade.

African countries performing well generally have several factors going for them: good or improving governance, strong national development strategies, commitment to increasing regional and global trade as well as debt cancellation and generous, effective funding streams from international donors. When these factors come together, investment and growth often follow.

The former Mozambican president, Joaquim Chissano, has just received the first Mo Ibrahim prize for leadership and good governance in Africa. Under his leadership, development assistance per capita increased from US$49 in 2000 to US$63 in 2004. Economic growth increased from two to eight per cent in the same period, and under-five mortality fell from 178 to 152 deaths per 1,000.

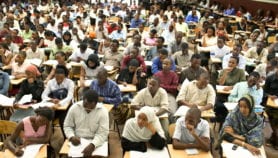

In Tanzania, corruption investigations have doubled as the government strengthens the rule of law. Aid per capita has also increased, from US$29 in 2000 to US$46 in 2004, with annual growth increasing from three to five per cent. Primary school enrolment leapt by over three million pupils and under-five mortality fell from 141 deaths per 1,000 children to 126.

Aid on its own is not the answer, but it has played a role in these African success stories.

We agree with Easterly that a one-size-fits-all, donor-led strategy doesn’t work, but we don’t believe that only "small, piecemeal" projects should be considered. With strong national ownership and adaptation to local needs, ambitious aid programmes can be effective.

The Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria is a good example of a donor mechanism directed by national needs. It is an independent multilateral organisation, funded mainly by G8 and European Union governments. All grants are based on nationally designed applications and drawn up in consultation with health officials, practitioners and nongovernmental organisations.

It is exactly the kind of needs-based planning that critics demand. Progress is measured against targets, and poor results mean funding is stopped.

Already the provision of millions of insecticide-treated bednets through Global Fund grants has helped cut malaria rates significantly in parts of Kenya and southern Africa. In Rwanda, where the fund supports HIV testing and the distribution of antiretroviral drugs, HIV prevalence is falling.

Development assistance can be an incentive for reform. To remain eligible for funding from the United States government’s Millennium Challenge Corporation, in 2006 the Madagascan government reduced the amount of capital required to start a new business by 80 per cent, sparking a 26 per cent increase in new business registrations. This brought hundreds of firms into the formal economy, better able to access credit and pay taxes.

As donor mechanisms for delivering aid improve, the monitoring of aid flows into recipient countries is also becoming more transparent. In Uganda, Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys, set up in cooperation with the World Bank and other donors, have detected corruption and leaks in budget allocations, especially for education. Between 1991 and 1996, only 13 per cent of the funding intended for education reached schools: by 2000 this had risen to 80 per cent.

Nigeria and Uganda have also established mechanisms to ensure that debt savings from the Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative are directed towards poverty-alleviation projects such as rural roads, agriculture, primary health, primary education and water supply.

Easterly and other critics are right that few people have been held accountable for aid failures and that only the poor are punished. That is why DATA also campaigns for democracy, accountability and transparency, for donors as well as for recipient countries.

Publication of failures and monitoring of best practice are needed to give policy-makers a better picture of what works and what doesn’t. Too many countries, including G8 members, are yet to sign and implement the UN Convention Against Corruption, and the implementation of OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) guidelines on doing business in developing countries gets little more than lip-service in many European Union and G8 capitals.

Critics argue that trade and investment will ultimately lift hundreds of millions of Africans out of poverty. Eventually, perhaps, but in the meantime 38 million children in Africa are out of school and healthcare is scarce.

In AIDS treatment alone, foreign assistance has helped save the lives of 1.3 million Africans over the past four years. This "grand plan" is driven not by donors but by demand from recipient governments, health workers and civil society groups. The market will ensure better distribution of medicines in future, but the public sector must lead the way –– and in Africa, that means more foreign assistance. A solution that calls for the market alone to solve this problem means death for millions.

Jamie Drummond is executive director of DATA (Debt • AIDS • Trade • Africa), www.data.org

More on MDGs

News

India’s shift to inclusive innovation is ‘a model to follow’

[CAPE TOWN] A leading Indian scientist and policymaker is calling on developing countries to adopt a ...03/01/13

News

Donors renew programme for African women researchers

[NAIROBI] Funders have renewed support for African Women in Agricultural Research and De ...12/11/12

News

More detailed data ‘needed to tackle hunger in Mali’

Using data from national household surveys could lead to a more accurate identification of09/05/12

News

African water atlas launched in French

[ABIDJAN] The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) has published a French version of its 'Africa Wat ...27/09/11

News

Fellowships for African women scientists a big hit

[NAIROBI] The African Women in Agricultural Research and Development (AWARD) fellowship programme has ...07/09/11

Opinion

Time for a grand re-think of grand aid plans

Aid donors should re-think their self-appointed role as saviours of the poor, and try more mod ...20/09/07

News

UK chief: Science ‘central to development strategy’

The British prime minister Gordon Brown has called on the global scientific community to apply its "cr ...02/08/07

Opinion

Developing countries need support to tackle MDGs

Developing countries need to strengthen their statistical systems to produce quality data for monitoring th ...27/04/07

News

UN hunger targets may increase water burden

If developing countries are to meet the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDG) to eradicate hunger, cr ...13/04/07