By: Priya Shetty

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

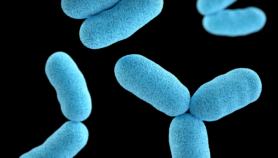

The World Health Organization (WHO) has launched a strategy to eliminate most cases of sleeping sickness, a disease that threatens millions in Africa, by 2015.

The five-point strategy plans to use a range of scientific approaches to reduce the number of people falling sick and dying from the disease.

WHO’s Africa committee launched the strategy when it met in Maputo, Mozambique, this week (22-26 August).

The strategy’s short-term goals include at least 80 per cent of African countries where the disease is widespread having national sleeping sickness policies by 2007.

The WHO also aims to train enough staff to work on disease control programmes by 2008. By 2012, it says, programmes should be in place to target the tsetse flies whose bites infect people with the sleeping sickness parasite.

By 2015, says the strategy, the number of cases should less than one per 10,000 people.

Meeting these targets will entail mapping the disease’s distribution across the continent, improving disease diagnosis and treatment, setting up surveillance systems, and controlling tsetse flies.

The sleeping sickness epidemic is worsening in parts of Africa. Research published in The Lancet this week shows that Uganda’s efforts to control the disease are failing badly.

In an accompanying article, the WHO’s Deborah Kioy and Nina Mattock say that because “tsetse flies are five times more likely to pick up an infection from a cow than a person” treating infected livestock is crucial for stopping an epidemic in people.

Investing in research is key, they say. Better scientific knowledge would help to develop better drugs, improved ways of controlling tsetse flies, and tests to detect infection earlier.

But for the strategy to stand a realistic chance of working, funding bodies must “reach for their wallets”, says Sanjeev Krishna, at St George’s Medical School, United Kingdom.

The WHO says sleeping sickness affects 300,000 to 500,000 people in a ‘tsetse’ belt stretching from Senegal in the west to Uganda in the east.

Also called African trypanosomiasis, the disease causes malaria-like symptoms that can develop into a severe neurological disease. Left untreated, it is fatal.

Link to the full paper in The Lancet*

Link to the commentary in The Lancet*

References:The Lancet 366, 745 (2005)

The Lancet 366, 695 (2005)

*Free registration is required to view these articles.