By: T.V. Padma

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[SYDNEY] Treating HIV-infected babies within three months of birth helps them live longer, a trial in South Africa has shown.

Preliminary results from the study on 377 babies were announced today (25 July) at an international HIV conference in Sydney, Australia.

The study, led by Avy Violari, paediatrician at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, and Mark Cotton, head of the Paediatric Infectious Diseases Unit at the University of Stellenbosch in Cape Town, found that starting anti-HIV drugs in babies less than 12 weeks old reduces early deaths by 75 per cent.

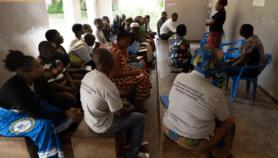

In the trial, two groups of babies received antiretroviral (ARV) treatment within 6-12 weeks of birth until their first or second birthday, while a third control group only received treatment when the signs of HIV infection appeared. Most countries initiate treatment in infants after they show signs of illness.

The results showed so strongly that early treatment was effective that the trial’s data and safety monitoring board immediately asked the investigators to switch the untreated babies to ARV treatment after a routine review in June 2007.

The immune system of babies is not fully developed and HIV-infected babies are especially vulnerable to disease progression and death during the first year, says Violari. Protecting infants in the first year of their life delays this.

“When to start treatment is a burning question in HIV research,” says Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health in the US.

“Evidence is beginning to mount that the longer you allow the virus to remain, the more damage it will do,” he told SciDev.Net.

Of the 2.3 million HIV-infected children worldwide, only 15 per cent in need of ARVs in low- and middle-income countries are receiving them, says Annette Sohn, assistant professor at the Division of Paediatric Infectious Diseases at the US-based University of California.

And in sub-Saharan Africa, only six per cent of children in need of ARV drugs get them.

Giving anti-HIV medicines to children faces considerable challenges: there are limited drugs for children; syrups that are easier to give to infants are harder to transport and distribute; and breaking adult tablets into smaller pieces often leads to over- or under-dosage.

Also, there are no fixed dose combinations — two or three medicines given as a single pill — for children yet. As children grow, the doses need to be changed.

There is also an absence of studies on how low birth weight and malnutrition — common to many poor babies in Asia and Africa — influence a child’s ability to tolerate the HIV medicine; on emerging drug resistance in children; or on optimal times to start and switch treatment.

Most countries also lack facilities to test weeks-old babies for HIV, using a genetic test called polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

But the findings from South Africa will put pressure on national governments and international donors to test and treat babies early, observes Sohn.