By: Catherine Brahic

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The H5N1 bird flu virus could get better at infecting people if it undergoes key genetic changes described in a study published today (16 March).

The researchers say their methods and findings could be used to monitor changes in the virus as new outbreaks occur, and could help scientists detect new, potentially dangerous mutations.

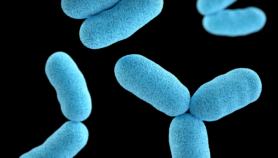

James Stevens of Scripps University, United States, and colleagues studied a protein, called HA, on the virus’s outer surface.

HA can attach to specific sugar molecules on animal cells, allowing the virus to enter them so it can replicate.

Currently, H5N1’s HA protein has a high affinity for sugars on the surface of bird cells, but is less able to lock onto human cells. As a result, despite being widespread and very infectious to birds, the virus has only infected 177 people since 2003.

But genetic mutations could make HA a better match for human cells, helping to turn H5N1 into a form that could spark a human flu pandemic. Until now, however, researchers did not know which mutations could make this happen.

The team worked on the H5N1 virus that killed a Vietnamese boy in 2004.

Introducing a change found in the HA protein of the virus that caused the 1918 ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic did not increase H5N1’s affinity for human sugar molecules.

But two mutations, both found in the viruses that caused flu pandemics in 1957 and 1968, did.

The findings “suggest a path for the H5N1 virus to gain a foothold in the human population”, write the researchers.

The technology the team developed could also prove useful. They used a tool called a ‘glycan microarray’ to quickly assess whether the modified HA proteins bind to human or bird sugar molecules.

Microarrays are small pieces of glass on which several hundred different sugar molecules are stuck. The researchers added fluorescently-tagged HA proteins to the slides, and then checked if they bound to any sugar molecules, or if they washed off the slide.

The researchers say this method could be used to rapidly determine whether new emerging strains of H5N1 have acquired the ability to bind to human sugars.

Link to full paper in Science ![]()

Link to accompanying commentary by Robert Krug in Science

Reference: Science doi: 10.1126/science.1124513 (2006)