Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

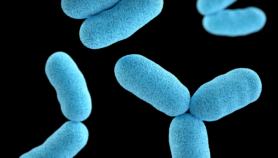

Recently, a tomato insect pest, Tuta absoluta, swept across Nigeria, devastating tomato fields and leading to immeasurable financial losses and emotional trauma. T. absoluta originated from the Andean region in South America.

The invasive nature of T. absoluta and its resistance to conventional insecticides make it difficult to control. If not handled properly, the effect of this pest could hold the continent’s agriculture hostage.

Protecting Africa’s agriculture

The emergence of this pest on the African agricultural landscape has rekindled pertinent questions regarding Africa’s capability to protect local agriculture and enhance international trade.

Surely, the World Trade Organization Sanitary and Phytosanitary (WTO-SPS) Agreement empowers individual country’s plant protection organisation to draw up measures that are strong enough to prevent the introduction of pests that may arise through trade. [1]

“The invasive nature of T. absoluta and its resistance to conventional insecticides makes it difficult to control.”

Mustafa O. Jibrin, Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria

Even before the WTO-SPS agreement, Africa’s protection of agriculture relied on the 1968 African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the 1985 protocol on protected areas and wild fauna and flora in the East African region. [2, 3]

With the increasing volume of trade between the continent and its partners in an era of globalised trade, however, it is difficult to assess how national plant protection agencies have transformed to handle the unique globalisation challenges.

The codification of the WTO-SPS agreement through the International Plant Protection Convention of the Food and Agricultural Organization as international standards for phytosanitary measures necessarily provide a framework for fairness in implementing national plant protection measures. The onus, however, is on individual national plant protection organisations to keep up with modern technologies such as utilising molecular biology tools and global positioning system-enabled tools in diagnostics and surveillance.

Having regional plant surveillance

According to the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, the pest badly affected agriculture in Egypt and Sudan in 2012. Since then, countries such as Ethiopia, Libya, Morocco, Senegal and Tunisia also had reports. By 2016, Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania had suffered varying levels of damage from this invasive pest.

Although these dates may not represent the exact period when the pests got into each country — as evidenced, for example, in the case of Nigerian where reports have been going on for the past two years on its presence — it nevertheless provides us with a guideline of how quickly pest species could spread once they spot a conducive climate.

The gains of having a regional plant surveillance system is easy to see as, apart from phytosanitary measures, invasive species do not necessarily have a defined border. They merely forage in the environment that suit their survival. On this, the European Plant Protection Organization (EPPO), established in 1951, serve as a good template.

“Thus, strengthening our national or preferably regional approach to plant protection could be key”

Mustafa O. Jibrin, Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria

The Inter-African Phytosanitary Council established at about the same time as the EPPO and strengthened by the Maputo declaration is yet to transition into a regional standard body such as the EPPO. Nevertheless, it still remains the most viable platform to lead the protection of Africa’s agriculture from invasive pests in all its forms. A slight re-focusing may be all that is needed.

Learning from the US programme

It is pertinent to draw up the example of the United States, which although sits just some few miles away from the South American coasts where T. absoluta is endemic, is free of this pest. What did they do right? Coordinated surveillance.

Knowing the destructive nature of this pest, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture launched a programme in 2011 to help report incidence and help timely eradication anywhere it is found.

The success achieved by this programme would have certainly be limited if individual states within the country did it on their own.

Bureaucracy often means that before valuable government responses would set in, if any at all, farmers must have suffered many forms of hardships from the consequences of poor harvest and crop loss.

The importance of being battle-ready on a grand scale rather than leaving those who are struggling to make daily lives take up arms against a pest they barely know about, is therefore not difficult to see. Thus, strengthening our national or preferably regional approach to plant protection could be key.

Mustafa O. Jibrin is a lecturer in Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria, and is currently a doctoral student and a graduate research assistant at the University of Florida. He can be reached at [email protected]

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

[1] The WTO agreement on the application of sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS agreement) (World Trade Organization, 2016)

[2] African convention of the conservation of nature and natural resources(African Union, nd)

[3] Protocol concerning protected areas and wild fauna and flora in the Eastern African region (UNEP, 21 June 1985)