By: Henry Neondo

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NAIROBI] Kenyan scientists are embroiled in a deepening controversy over whether Kenya should lift a ban on the pesticide DDT in a bid to reduce deaths from malaria.

A government-commissioned taskforce is poised to reveal its advice on whether the pesticide should be reintroduced. Meanwhile sharp divisions are appearing between two of the country’s leading research organisations, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), both based in Nairobi.

Researchers from ICIPE and others argue that the health and environmental risks of reintroducing DDT are considerable, and that the East African region as a whole would suffer if the ban were lifted. But researchers from KEMRI, led by director Davy Koech, argue that the pesticide is needed to combat malaria, which kills 700 Kenyans a day.

“Anything that can reduce malaria deaths by 80 per cent should be given another thought,” says Koech. The disease, which is transmitted by mosquitoes, currently accounts for up to half of all hospital admissions in Kenya. KEMRI researcher John Githure argues that Kenya’s decision to ban DDT in 1990 was taken hurriedly and without adequate data.

But opponents of lifting the ban — which was mooted earlier this year by the minister for environment and natural resources, Newton Kulundu — point to the fact that the pesticide is forbidden in many countries because of its harmful effects on humans and the environment.

DDT is one of 12 chemicals targeted by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, a global treaty to limit the use of chemicals that that are toxic to humans and wildlife, and that remain intact in the environment for long periods. Most of these chemicals are subject to an immediate ban. But a health-related exemption has been granted for DDT, which is still needed in many countries to control malarial mosquitoes.

This is not a reason for lifting the ban, however, according to Onesmo K. Ole-MoiYoi, director of research and partnerships at ICIPE. “The whole debate on DDT should be looked at in the wider context of economics, environment and Kenya’s external markets for products such as horticultural and fish products,” he says. This is especially relevant now, he adds, at a time when Europe is tightening its restrictions on insecticide residues on East African products.

This point is reinforced by Deborah Nyarunda, administrative secretary of the Uganda Fish Processors and Exporters Association (UFPEA), who argues that the use of environmentally unfriendly chemicals has had a heavy toll on the fishing industry from Lake Victoria, which is shared by Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. This was the reason for a European ban on imports of fish products from the region between 1997 and 2000, she says.

Reintroduction of DDT in Kenya would require all countries in the region to invest in equipment needed to monitor levels of the chemical in products destined for export, says Clauda Maoha, deputy director of testing at the Tanzania Bureau of Standards

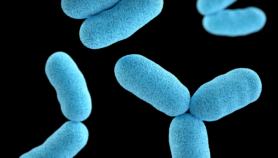

In any case, says Ole-MoiYoi, several environmentally friendly ways of controlling malaria already exist. For example, Kenya will soon start producing a type of bacteria — Bacillus thuringiensis — that kills mosquito larvae, and which is currently imported from the United States. This could provide an alternative effective malaria control strategy without such severe impacts on the environment, he says.