By: Catarina Chagas

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[SALVADOR, BRAZIL] As a Brazilian science communicator, I am interested in how people communicate science in other Portuguese-speaking countries.

Although it is easy for me to find projects in Portugal, it is hard to get to know what is happening in other regions, such as Africa, due to lack of information — and that’s why I was excited to see what would come out of a panel focusing on Portuguese-speaking Africa presented this week here at PCST2014 (The 13th International Public Communication of Science and Technology conference).

João Emídio Cossa, a representative from Mozambique’s Ministry of Science and Technology, gave a good presentation. A commitment to science communication was part of the country’s very first constitution, in 1975, he said.

The government is responsible for several science communication and public engagement initiatives, such as science fairs and magazines. Local newspapers publish science articles and there is room for science shows on TV. And, according to Cossa, there are growing numbers of NGOs dedicated to science communication.

The Ministry of Science and Technology also tries to foster capacity building in science journalism. However, interest may not yet be big enough: for example, the government offers a grant to study science journalism in Brazil, but this is the least-sought-after grant among several, including one to study engineering.

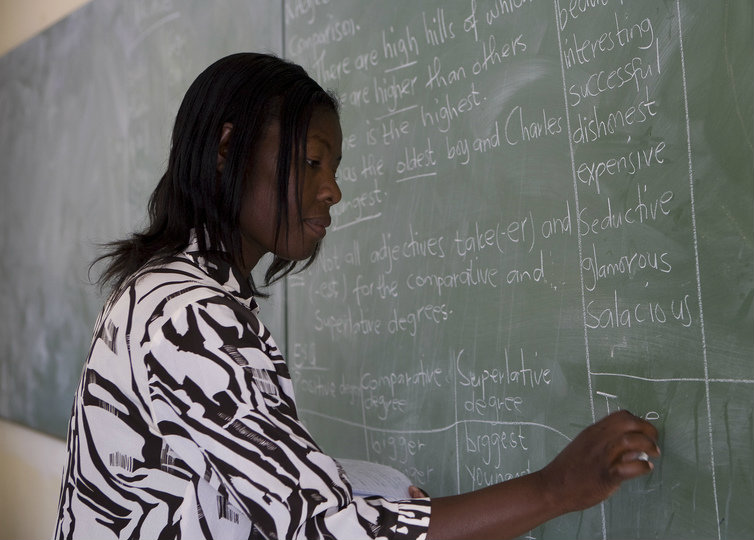

Language is a major challenge to the communication of science in Mozambique. Portuguese is an official language, but is only spoken by around five per cent of the population. Everyone else speaks a diverse number of local languages, and they are still figuring out how to translate and adapt science communication materials: first from the international language used for science, English, and then from Portuguese.

The need for English-language education in these countries was also highlighted by Elizabeth Rasekoala, founder and director of the African-Caribbean Network for Science & Technology, after the session.

She saw it as a main way to enable local people to take up high-skilled jobs in multinationals involved in areas such as the booming oil industry in Angola and Mozambique — instead of relying on an imported workforce.

“It’s a no brainer, I’m afraid,” she said.

Cape Verde has been making major investments in education. In 1975, at the time of its independence, 75 per cent of the population were illiterate.

According to Adalberto Furtado Varela, from the country’s Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation, about 90 per cent of people are now literate.

But Varela said the government invests so much in higher education that it faces a new problem: there are not enough jobs for people coming out of it. Cape Verde is now trying to stimulate entrepreneurship to change that, he said.

It was also interesting to know that for every 100 men in higher education, there are 145 women. Yet, they still struggle to engage the communities on the tiniest of islands.

Maximino Costa, a journalist from Sao Tome and Principe, said that digital inclusion is the main concern in his country, with efforts being made to establish optical fibre networks to allow internet connections at higher speeds and lower cost.

The session left me curious about what is going on in science communication and public engagement in science in other Portuguese-speaking African countries — it was a pity that a delegate from Angola did not attend the conference.

It would also be interesting to see what efforts are being made outside governmental circles, by local media and research institutions, for example.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net's Global Edition.