25/11/17

Resilience from people on the edge of global change

Sand, wind, and sky — a fisherman carries the day’s catch in Madagascar. Herding and fishing need large areas of land if local communities are to keep up with their livelihoods.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

A Mongolian herder. Communities in the Gobi Desert, like those on the shores of Southern Madagascar, rely on the natural world to survive in remote areas and a changing environment. Their resilience strategies are strikingly similar.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

A pair of pirogues in Madagascar. Moving is fundamental for both working and socialising. Fishers often meet in the middle of the ocean — as Mongolian herders meet in the desert — to exchange views on how the environment is changing.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

Men and women work together to milk a camel in Mongolia. Livestock farming is a family effort. Since the structured community was formed as a response to increasingly harsh winters, families have helped each other, for example in hay making and preparing for winter.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

Seaweed farming changed the life of Narinchu Marcelline, now treasurer of the association of sea-cucumber farmers in Tampolove. As a result of this work she has a income, and a key role in the community. Women are increasingly involved in sea-farming activities that were once men’s work — a form of adaptation.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

Sheep and goats in the Gobi Desert. As with seaweed and fish in Madagascar, these products are crucial for the local economyin the arid highlands of Mongolia. The community has created a fund that compensates individual households in case of severe herd loss due to extreme weather events.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

A sea cucumber. A promising product of aquaculture, sea cucumbers offer fisher communities new commercial opportunities. As an example of diversifying activities, this is an effective adaptation strategy, according to experts.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

Batkhuyag Tseveravajaa, head of the Uvurkhangai community in the Gobi desert, with two herders from the same community display the national and provincial awards they received as an acknowledgement for having taken the initiative to improve pasture managementto solve environmental challenges.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

Until about ten years ago a fisherman could earn 6 to 20 dollars per day, villagers from the Velondriake community have said. But stocks have now collapsed, and fishing is worth 1-2 dollars per day. Aquaculture could be a solution to making a living based on marine resources.

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

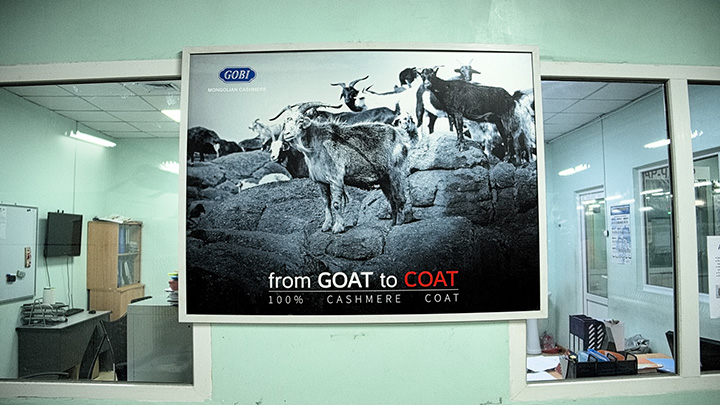

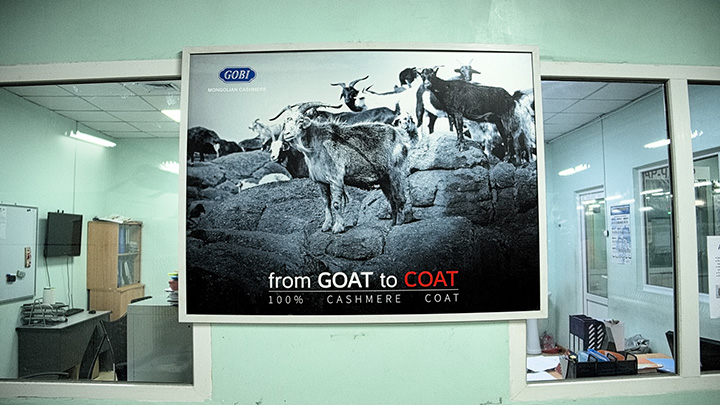

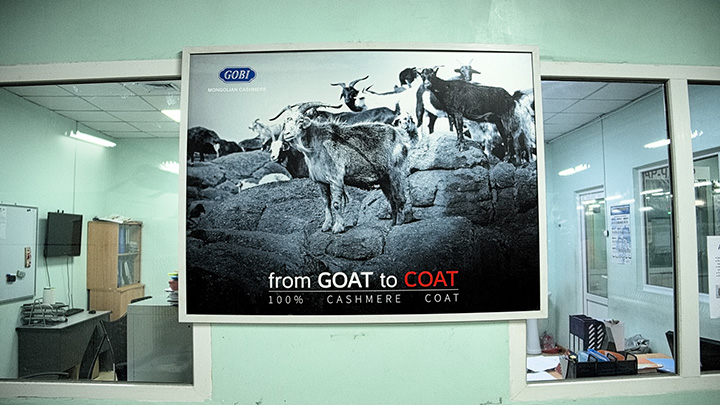

“From goat to coat”. Cashmere is a profitable resource threatened by cheap imports and environmental changes challenging production for most nomads. Since 1960s, the number of goats rose from 4.5 to 23 million, leading to overgrazing and falling wool prices. Will the nomads adapt to the new, competitive, market?

Jacopo Pasotti, 2017

By: Jacopo Pasotti

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Communities that strongly depend on natural resources, such as Madagascar's fishermen and Mongolia’s nomads, are vulnerable to climate and environmental changes. They are also among emerging cases of resilience from people on the edge of what’s livable as global change advances.

This image gallery shows two examples of resilient communities looking for solutions to these changes. Depsite their differences, the Uvurkhangai in the Gobi desert and the Velondriake in Southern Madagascar share similar challenges and vision.

Mongolia is facing a rapid increase in average temperatures, expected to exceed 2 degrees Celsius in the next 70 years. The frequency of extreme events — such as heavy summer rains or colder winters, known as dzuds — is growing. In the dzud events of 1999–2002 and 2009–10, the country lost 30 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, of the national herd of cattle, sheep, goats, camels and horses— livestock that serve as important sources of meat, wool and milk.

“After the disastrous winters of [the] early 2000s many herders formed communities for the management of pastures,” says Tunga Ulambayar, ecologist and director of Saruul Khuduu Environmental a Research, Training and Consulting, an NGO based in Ulaanbatar. “It is an attempt to adapt to [the] occurring environmental changes. It allows them to better manage their pastures, pool labour, and slow down land degradation,” she explains.

In a 2015 study published in the journal World Development, Ulambayar found that these structured communities were crucial in reducing the herders’ vulnerability to dzuds.

Across the equator, Madagascar is facing similar challenges. It is one of the poorest countries in the world, with over 75 per cent of all households living under the poverty threshold. Small-scale fisheries, an important source of income and subsistence, are over-exploited. This has led the government to set up a system of marine reserves in the hope of safeguarding marine biodiversity and ensuring the seas remain productive.

Since the late 2000s, community-based farming of sea cucumber and seaweed has increased as result of research and development projects involving fishermen, private companies, NGOs and public institutions. "Thanks to our studies and fishers training, communities understood that they needed to look for alternatives to fishing", says Gildas Todinanahary, from the Institute of Fisheries and Marine Science at the University of Toliara. “We are now trying to introduce corals and sea horses cultivation.”

The Shared Horizons project has received funding support from the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme operated by the European Journalism Center.

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net's global edition.