By: Maha Rafi Atal

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Last month, world leaders gathered at a summit in New York, United States, to launch the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), successors to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). I’ve covered the MDGs since 2008, focusing on the private sector’s role in achieving them. But over the years the subject hardly came up in UN discussions.

This summit was different, with multiple events targeting the private sector, and businesspeople roaming the UN compound.

That’s not an accident. When the UN began reviewing MDG progress in 2012, the results in areas such as hunger and sanitation were sobering, according to Olav Kjørven, then a special advisor to the UN Development Programme.

“It is when businesses see SDG success as an opportunity to compete with their peers that private-sector contributions are likely to take off.”

Maha Rafi Atal, University of Cambridge

His team decided that many targets — for example to do with employment, the environment and the delivery of key services — could not be achieved without the private sector.

Yet the MDG process excluded the private sector from planning. The goals launched in 2000, amid aggressive, but unsuccessful, campaigning against the Washington Consensus pro-market economic policies. "Nobody was thinking about the private sector because the private sector had won the debate,” Kjørven explained.

Then, after the financial crisis, people realised that to make progress on energy, food, liveable cities, and job provision, the private sector would have to be brought into this process “from the get-go”, Kjørven told me.

With this in mind, SDG planning proceeded along three tracks: consultations with policy experts, national consultations of citizens’ priorities, and private sector consultation, managed by the UN Global Compact. The process has highlighted two key ways tech companies can make a difference.

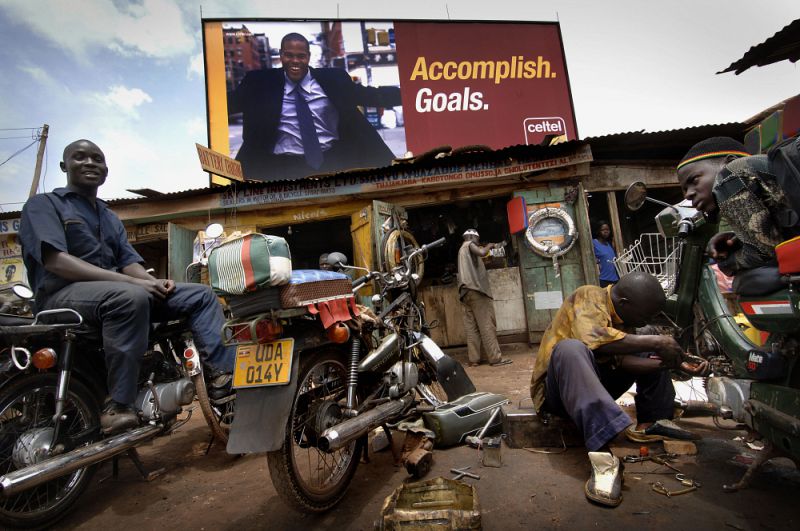

First, the priorities survey helped put access to technology on the agenda. Goal 9 on infrastructure development includes a target to “provide universal and affordable access to the internet in least developed countries by 2020”. In an era when global job growth is likely to come from high-tech industries, and where all businesses increasingly require the use of technology, the digital divide between rich and poor countries is a major obstacle to development.

Similarly, Goal 17 on international partnerships emphasises technology as a key area where rich countries can transfer expertise to poor ones. This is an opportunity for technology companies that can distribute phones and tablets, install telecommunications infrastructure at low cost and help other industries use technology to thrive in the global South.

Second, data companies have helped develop tools to monitor SDG progress. These include telecoms firms BT and Verizon, which support UN initiative the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, an online platform where development practitioners, governments and businesses can share practices and progress related to the SDGs.

Also crucial are data consultancies such as GRI and AccountAbility, which produce corporate sustainability reports for investors and publish their measurement standards so companies can use them in their own reporting. At the New York summit, Michael Meehan, CEO of GRI, said the market and fears over reputation spur firms to operate more sustainably. Establishing widespread standards for measuring and reporting on corporate sustainability initiatives can enable the development community to track and compare firms, and their progress on helping achieve SDG targets.It is when businesses see SDG success as an opportunity to compete with their peers that private-sector contributions are likely to take off.

Maha Rafi Atal is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, where she is researching the political effects of multinational firms acting as public service providers in the developing world. She was previously a journalist, including at Forbes, where she covered the intersection of business, development and international affairs. You can contact her on [email protected] or follow her on Twitter: @MahaRafiAtal