By: Jan Piotrowski

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

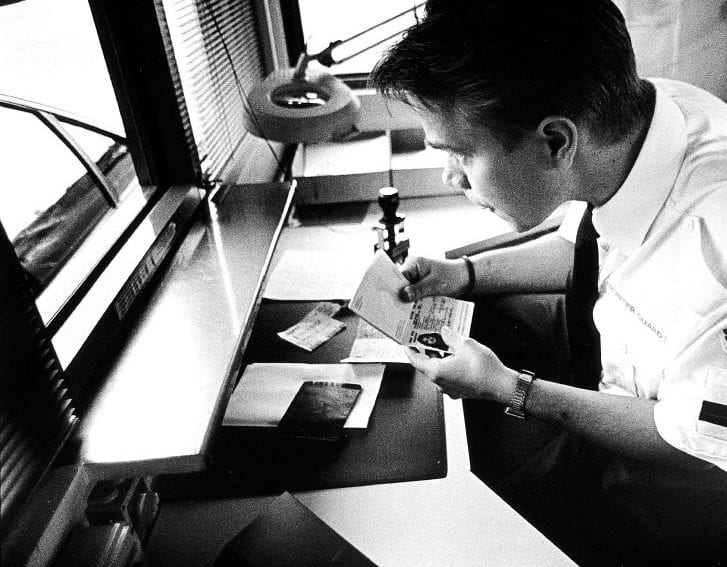

Governments must address the “visa labyrinth” that restricts the work-related travel of scientists and engineers if they want to improve progress on international issues such as climate change and build scientific capacity in the developing world, experts have warned.

Martyn Poliakoff, foreign secretary of the Royal Society, United Kingdom, says that, while concerns over immigration are legitimate, current policies that entail long and complicated visa application processes are stifling scientific collaboration and the exchange of ideas.

“While everyone accepts that diplomats must travel for their jobs, I don’t think it is acknowledged that scientists and engineers need to travel,” he tells SciDev.Net.

“The visa labyrinth that scientists must navigate is often interpreted as a message to ‘stay at home’.”

In an editorial published in Science last month (31 January), Poliakoff says that the free-flow of expertise is essential for tackling global challenges, such as climate change or antibiotic resistance, and for training a new generation of scientific leaders in the developing world.

He calls on leaders of the G8 leading economic nations, who are scheduled to meet representatives of national science academies in Moscow, Russia, in April to acknowledge the need for a “single, worldwide scientific community”.

“[Governments] should recognise the need for free and widespread international exchange of researchers in science and engineering, especially for the younger generation,” he writes.

The international flow of scientists is “absolutely vital” for doing good science, says Sarah Main, director of the Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE), a UK-based advocacy group.

Over the last few years, CaSE has helped to win various concessions on migration laws that have aided scientists coming to the United Kingdom, she says. These include the creation of an ‘exceptional talent’ tier for classifying immigrant eligibility and the scrapping of a cap on the number of skilled migrants, she adds.

But despite these advances, barriers still prevent researchers from obtaining UK travel visas, says Main.

For example, a recent round-table event run by CaSE, and attended by civil servants, researchers, NGOs and business leaders, heard how scientists from countries where higher levels of immigration fraud originate, face more-burdensome application processes, she says.

The discussions also covered the case of an organiser of a malaria conference who had difficulty securing the attendance of researchers from countries where the disease is endemic, says Main.

Decision-makers, for their part, have been keen to start a dialogue and there are even signs of progress, such as the UK Home Office working on making its online application process simpler to use, she adds.

Furthermore, scientists are failing to exploit the various pathways available to them, such as the underused exceptional talent tier, and so the community must promote these options, says Main.

Poliakoff agrees that scientists must take responsibility for highlighting the issue.

“In the longer term, researchers across the world need to be more active in helping politicians understand how science is conducted and how it is affected by international issues such as visas,” he says.