By: Sara Naraghi

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

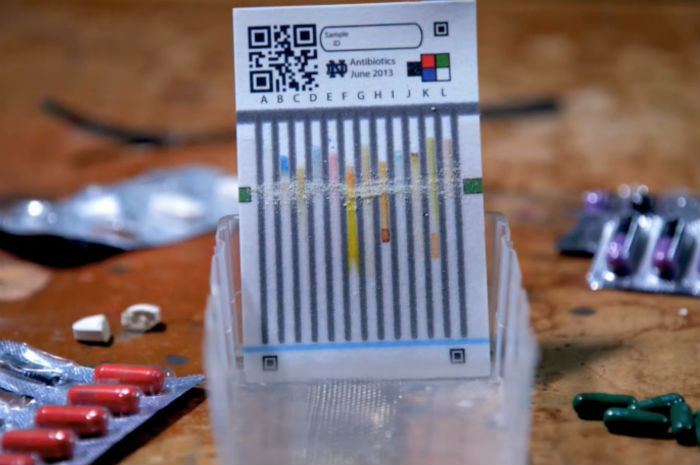

Scientists have designed a cheap and easy-to-use paper test card that uses colour coding to detect fake antimalarial drugs.

To test a pill or tablet, it is crushed and swiped across the card that is then placed in water. After only three to five minutes, a pattern of coloured bars is revealed.

The idea is that if this pattern differs from the unique colour barcode produced by pure samples of that drug, the batch of drugs is labelled as suspicious and sent to a laboratory for further analysis.

“I think these will become attractive targets for people who are making fake or low quality drugs.”

Marya Lieberman, University of Notre Dame

The test is meant to be deployed in pharmacies before drugs are offered for sale, and in customs offices, according to the researchers behind the invention.

“The initial goal was to develop a way that pharmacists could do a quick analysis, like a screening test, when they didn’t have a lab,” says Marya Lieberman, a chemist at the University of Notre Dame in the United States. She says the technique was designed with poorer countries in mind.

Lieberman and her colleague Abigail Weaver, a postdoctoral researcher at the same university, published a study on the cards in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene last week (20 April). The cards are for non-artemisinin-based antimalarials.

According to the pair, around a third of malaria drugs in Sub-Saharan Africa are of poor quality: either containing less of the active ingredient than advertised or being adulterated with things such as corn flour, paracetamol or aspirin. Substandard drugs can cause drug resistance without effectively treating the illness, while contaminants can even kill patients.

The cards are intended for use by trained drug testers rather than patients, as they can be confusing at first glance, according to the team.

Each card has 12 bars that react and change colour once exposed to a drug, pinpointing the presence of up to six different antimalarials. The bars also indicate how much of an active ingredient is in the drug, and whether the drug was diluted with contaminants or otherwise stretched.

Paul Newton, a tropical medicine researcher at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, says the cards are innovative but may not solve the problem of falsified medicines.

“Medical supply chains differ remarkably among countries,” he says, explaining that fake drugs can enter healthcare systems at different stages. He says the test is “useful at a pharmacy level”, but may fail to prevent fake drugs being introduced higher up in the supply chain.

Lieberman and Weaver are working to make each card more affordable, as the current cost of just under 50 US cents is still too high for many poorer countries. They are also looking into making test cards for drugs to treat conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, which are increasingly prevalent in the developing world.

“I think these will become attractive targets for people who are making fake or low quality drugs,” Lieberman says.

References

Abigail A. Weaver and Marya Lieberman Paper test cards for presumptive testing of very low quality antimalarial medications (The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 20 April 2015)