Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[YAOUNDÉ] Researchers in Cameroon have reported success with a vaccine that rids pigs of a parasite that can cause a potentially fatal brain disease in humans.

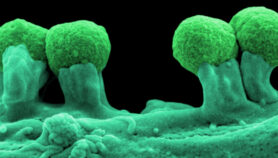

The parasite Taenia solium — known as the pork tapeworm — is the leading cause of preventable epilepsy in the developing world (see Tapeworm link with epilepsy ‘far higher’ than thought).

It is transmitted from pigs to humans through eating undercooked meat and can also spread among people from exposure to T. solium in human faeces. The parasite is common in areas where sanitation is poor, and where pigs and humans live side-by-side, leading to constant re-infection despite current control attempts.

Pork tapeworms can live in humans without causing serious harm. But if human food becomes contaminated with the parasite’s eggs, they hatch in the intestine and travel to the brain, causing neurocysticercosis — a potentially fatal brain disease with symptoms including cysts and seizures.

Researchers trialled a vaccine — developed at the University of Melbourne, Australia — for the parasite in more than 200 three-month-old piglets in Cameroon. All the piglets were given a drug to kill any parasites present before vaccination and half were inoculated with three doses of vaccine.

The piglets were then distributed in vaccinated and unvaccinated pairs to pig farms in the north of the country, according to Emmanuel Assana, a researcher from Cameroon at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium, who conducted the trial, described in the International Journal for Parasitology this month (April).

The team tested the piglets after about a year — at the age when they are slaughtered for meat and so can transmit infection to humans — and found live parasites in 20 of the unvaccinated piglets and none in the vaccinated animals.

"We demonstrated that the vaccine is highly protective in village pigs," Assana told SciDev.Net. "The vaccine was not just able to decrease transmission of the parasite but to completely eliminate any transmission to the pigs involved in the trial."

Assana said that combining the vaccination with a parasite-expelling drug is a straightforward procedure that has the potential to control T. solium transmission in endemic areas.

The researchers have yet to determine what the cost of the vaccine could be in large-scale production. They want to improve the vaccine by altering it so it needs to be given on only one occasion, rather than the three injections used in the Cameroonian trial, and also hope to change it to an edible vaccine rather than an injection.

"If further field trials and large-scale production of the vaccine proceed well, we could expect it to be available for use in 3–5 years," Marshall Lightowlers, a researcher at the University of Melbourne who led the development of the vaccine, told SciDev.Net.

References

International Journal for Parasitology doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.01.006 (2010)