By: Lou Del Bello

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Research into livestock cloning, gene banks and vaccines could result in more robust animals, ILRI's director-general tells SciDev.Net.

Smith was born in Guyana, in the Caribbean, where he was raised on a small mixed crop-and-livestock farm. He is a graduate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States, where he completed a PhD in animal sciences. Before joining ILRI, Smith led the World Bank's Global Livestock Portfolio and held senior positions at the Canadian International Development Agency.

He spoke to SciDev.Net about ILRI's plans for the world's first gene bank for Africa's threatened indigenous livestock breeds, the need for novel vaccines to tackle livestock diseases that can damage the livelihoods of Africa's many smallholder farmers and the importance of improving livestock productivity to feed Africa's growing population while reducing its environmental impact.

Why is livestock important for food security in the developing world?

However, livestock animals can also harm the environment, mostly by emitting methane and other greenhouse gases, and by degrading land and water sources. They get a lot of negative attention and, in many cases, investments in research could help deal with these problems. Bilateral donors, foundations, developing countries themselves and banks could play an important role in supporting research on new solutions for the improved productivity and sustainability of small-scale livestock systems.

What is the best way to achieve sustainability?

To do so, the first step is to improve feed supplies. In much of the developing world, the most important feeds are residues from edible crops grown for human consumption. By finding ways to improve the quality and digestibility of these residues, without sacrificing the yield of edible crops, we could improve the productivity and efficiency of smallholder livestock systems.

In this field, research takes advantage of both local and international expertise. For example, a lot of rice and maize varieties used to feed livestock in the developing world are developed at the international level. In Africa, there are several international research centres that are similar to the one I lead but that deal with staple crops of the poor rather than livestock. But although they are based in the developing world, they work within the international research system.

How important is animal health in livestock management?

Large-scale industrial farmers can afford to protect their stock from disease and treat those animals that become sick. They still suffer losses, but the ones who suffer most are the smallholders in developing countries who are generally unable to pay for expensive treatments.

That's why we are looking at vaccines more than at new treatments. We work almost exclusively on the challenges posed by poverty.

For African farmers, the income from a milking cow can meet many of a household’s needs, as well as fund their children's education. The loss of a single dairy animal can be devastating to a smallholder.

Vaccines for animals are important, but Africa also needs funds for human health. Do you think that the two fields must compete for money and policymakers' attention?

In the case of human and animal research, the underlying bioscience is the same and there are many diseases that afflict both livestock and people. Brucellosis, rabies and tuberculosis are among the most widespread of these, but there's also concern about avian influenza. Better control of such diseases in animal populations through vaccines could reduce their spread to people.

There are great synergies between medical and veterinary research. By working more closely together through joint investments, we can achieve more rapid improvements in both human and animal health.

For example, scientists have been working for many years on a disease called trypanosomiasis, better known as sleeping sickness, which affects both humans and livestock. Hundreds of thousands of livestock die every year from it. In terms of biology, the sleeping sickness parasite behaves like malaria and, just as is the case with that disease, we weren't able to develop a protective vaccine. Other methods have been tried, such as traps to control the vector, the tsetse fly, but these have proved largely unsustainable.

However, it turns out that the baboon is resistant to all forms of both human and animal trypanosomiasis, and just one gene controls this resistance.

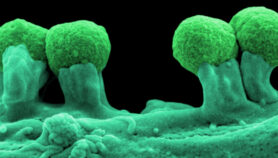

When ILRI partners at New York University inserted a synthetic copy of this gene into mice, the gene protected the mice from trypanosomiasis when they were subsequently infected with trypanosome parasites. Another project partner, at the Roslin Institute, in the United Kingdom, recently succeeded in transforming cell lines with the disease-resistant gene. It is early days yet in this project, but if all goes well, the synthetic gene will be inserted into a cloned calf to determine if it can protect African cattle against trypanosomiasis. ILRI recently succeeded in producing a healthy cloned calf.

If we find that this disease resistance can be passed to the calf, in the long term we will be able to breed cattle naturally that are resistant to trypanosomiasis and make these healthy and hardy animals available to farmers.

ILRI is calling for the creation of a livestock gene bank. What would it look like and how could it benefit people?

The idea is not to preserve all species, but only those that together provide the greatest diversity of indigenous stock. We are still looking for the most effective way to realise a livestock gene bank.

Samples of livestock semen and eggs would be preserved in cold storage, a method called 'cryopreservation'. Stored samples from locally bred animals would be duplicated in gene bank facilities in their countries or regions of origin.

We are trying to come up with the most cost-effective ways of working with partner organisations to make sure that this happens. We don't have the financial resources to undertake the project at the moment, but we are working to attract funders by highlighting its scientific and development advantages.

The main benefit of a genetic repository for livestock in the shorter term would be to prevent biodiversity losses; in the long term, such a repository would also be a precious research tool. By searching within the samples, we could isolate genetic material controlling for resistance to particular diseases or that had traits useful for adapting to altered climate and other change. The genomic material we would collect and store could thus carry solutions for the world's future challenges.

Q&As are edited for length and clarity.