By: Eliot Barford

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

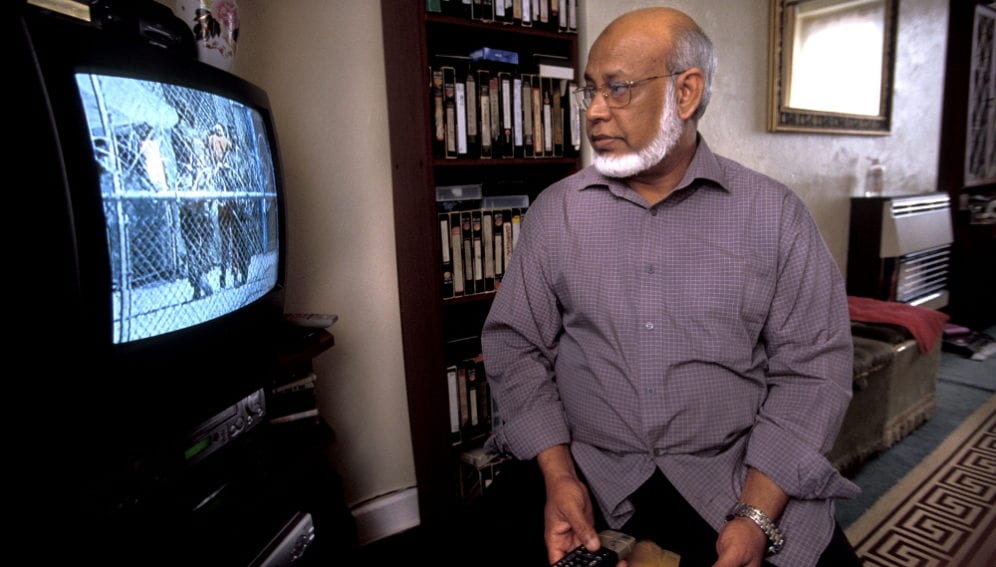

When British TV audiences watch stories about suffering in less developed countries, the main response is indifference, according to a study.

News reports are particularly poor at moving viewers, although non-news programming can produce deeper and more nuanced understanding of the issues it covers, the study found.

“This is not the same as saying that they didn’t want that news.”

Martin Scott, University of East Anglia

For the study, published in Media, Culture & Society last month, 108 people participated in focus groups to discuss how they respond to seeing less well-off people in other countries on television. Forty-eight of them then kept diaries for two months recording how they felt about the programmes as they watched.

“They wrote an entry in their diary every time they encountered something to do with people from ‘countries poorer than ours’,” explains author Martin Scott, who lectures on media and development at the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Forty-six people then took part in a second round of focus groups.

There were two key findings. The first was that “people were largely indifferent to distant suffering” they saw on television, he says. Some simply “didn’t care”, while others felt glad that they were not affected. “In other cases, it was a begrudging acceptance that this is just what happens,” says Scott. Some participants felt resistant to being made to feel a certain way, he adds.

But Scott emphasises that “this is not the same as saying that they didn’t want that news” and that viewers thought it was important to be informed.

Young men were the least empathetic, with older women being most compassionate. This broadly reflects the trends in charity donation statistics, such as those published by the UK’s Charities Aid Foundation, a group that offers advice to the charitable sector.

The second key finding was that non-news factual output did more to make audiences care than news. Scott found that such programmes could stimulate more complex understanding and humanise sufferers more fully. Documentaries and current affairs shows were best at inspiring eliciting emotional responses.

Scott reports a “surprising absence” of references to NGO television appeals for donations: the participants “just didn’t talk about these things very much,” he says. When they did, resistance was again a common response.

This study “adds a much stronger basis for something that we already suspected,” says Scott. The research aimed to understand why people in the developed world do not care more about ‘distant suffering’ when technology facilitates widespread awareness of it. He argues that this is important since the case for much development assistance and aid is made on the basis of suffering.

Jonathan Corpus Ong, a media and communication lecturer at the University of Leicester, United Kingdom, who has also studied representations of suffering on television, calls the study a “necessary intervention” in a field with a dearth of empirical audience research.

“I think the use of a diary method is actually quite inspired,” he adds, explaining that the technique encourages people to express what they feel passionate about in fleeting moments. He says such data could offer insights for NGOs.

On the other hand, Ong suggests that the study is limited because it lacks data that would reveal whether viewers changed their behaviour in response to what they watched, for instance by donating or volunteering.

Brendan Paddy, head of communications at the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC), which coordinates several major UK aid charities during crises, says that the development and aid sectors are already interested in increasing the coverage of global suffering “across the whole range of different broadcast product, not just news”.

He cites the work of the International Broadcasting Trust, which seeks to build interest in development on TV, on radio and online. “I don’t doubt that [Scott is] right that we could get a higher level of engagement with different kinds of coverage,” he says.

But Paddy notes that DEC’s experience, such as a recent call for aid for Filipinos affected by Typhoon Haiyan, shows that ‘temporal proximity’ to the event and its resulting news coverage is the “biggest single indicator of engagement interest”. This means that immediate and dramatic news broadcasts and appeals remain most effective at attracting public support, despite their limitations in involving viewers, he says.

> Link to full paper in Media, Culture & Society