By: Katia Moskvitch

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Data journalism offers a new way to visualise and discuss development challenges, but is being hampered in the developing world by a lack of open data and stricter laws, says an expert.

Despite this form of journalism being in its infancy in developing nations, there is a lot of innovation in this field in some newsrooms. Argentina’s newspaper La Nacion, for example, won one of the awards at last year’s Data Journalism Awards (DJA) for its investigation into political corruption.

“Data journalists are recognised as being at the forefront of newsroom innovation.”

Bertrand Pecquerie, Global Editors Network

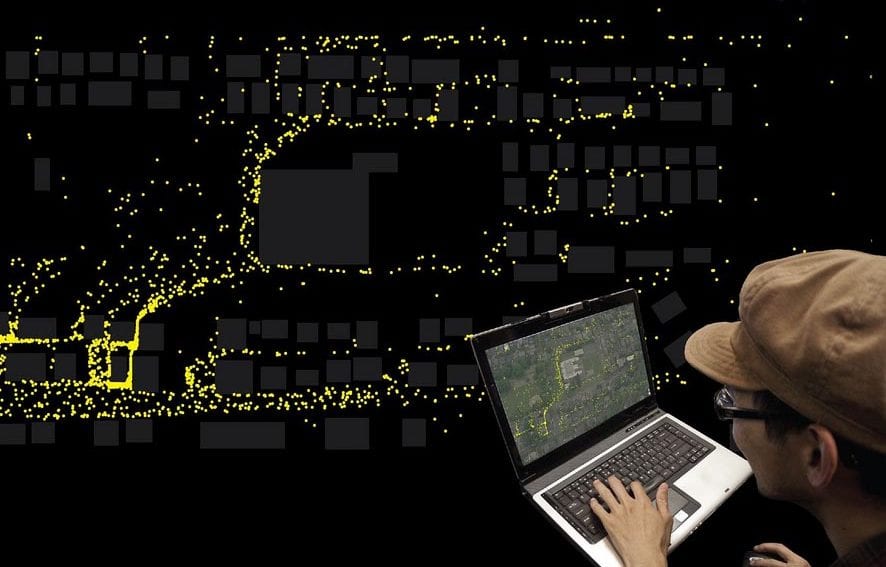

Bertrand Pecquerie, the chief executive of the Global Editors Network that organises these international awards, says data investigation and visualisation offer a way to change how people view many issues, such as global warming, slums and poverty. “Changing our perception [regarding] these problems is the first step to solving them,” he says.

Data journalism is now moving into the mainstream thanks to open data and access to more public and private databases, says Pecquerie. “Today, the data journalists are recognised as being at the forefront of newsroom innovation,” he tells SciDev.Net.

Last year, there were 350 submissions to the awards. More than 85 per cent came from developed countries. Among developing nations, only entries from Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Kenya, the Philippines and Venezuela made the shortlist.

“Clearly, data journalism is at an early stage in emerging countries,” says Pecquerie. “The real barrier is access to open data, and the laws are still friendlier in, [for example], Sweden and Norway than in Nigeria or Pakistan.”

“Nevertheless,” he adds, “we were impressed by the innovation process within some newsrooms.”

He cites the example of La Nacion, which scooped its award for reporting into the expenses of the Argentinean Senate from 2004 to 2013. The journalism led to a judicial investigation of vice-president Amado Boudou.

The team responsible built and analysed data sets of the expenses, uncovering numerous spending irregularities and instances of corruption.

Florencia Coelho, a member of the newspaper’s data team, says: “We found out that there were trips that never happened but were reimbursed, and purchases of luxury decoration above the legal [spending] limits for direct purchases.”

Pecquerie called La Nacion’s work “remarkable”, adding that the newspaper now produces quality pieces on a regular basis with the help of its data journalism department.

One way of giving data journalism a boost in developing nations is for more journalists and media from these countries to apply for the annual awards, says Coelho.

“I hope that more developing countries are listed as finalists this year, because it would make the power of data journalism accessible to all journalists or newsrooms, in all countries, against all odds,” she says. “That could mean more accountability and transparency for their governments.”

The awards aim to inspire other journalists by showcasing outstanding work, highlighting best practice in data journalism and showing its value to editors and media executives.

The 2014 awards were launched last week and are open to applications until 4 April.