By: Catarina Chagas

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[SALVADOR, BRAZIL] Let local communities find and share solutions to local issues — that is the philosophy behind the Cobra project, an attractive idea I came across last week at the 13th international Public Communication of Science and Technology conference (PCST2014).

Cobra works across the Guiana shield, a remote mountainous region covering parts of northern Brazil, Columbia, French Guiana, Guyana, and Suriname. It’s an area where indigenous people have traditionally managed their own lands, though according to Cobra’s website, this knowledge is rarely used to guide development priorities. In this context, Cobra works with indigenous people to document their local expertise, sharing it with other groups of local people in the hope that it can be used to provide solutions to the challenges of managing the important natural resources in the area.

“Indigenous communities are frequently portrayed as ‘undeveloped’ and in need of external assistance in health, education, employment, agriculture,” said Andrea Berardi, from the Open University, United Kingdom, during his presentation at PCST. Yet he believes these groups can produce their own solutions to problems they face in their regions.

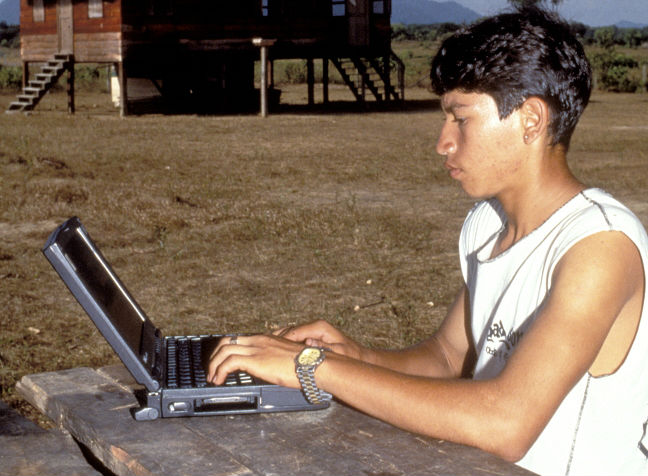

Berardi is part of COBRA Project team. Together with his colleagues, he organises meetings in indigenous communities to talk about how they could face resource management challenges. Using information and communications technologies the groups record and share community-owned solutions for environmental, social, health and other problems.

“Communities have the expertise and local knowledge to resolve problems,” said Berardi. The problem, he explained, is the disconnect between the scientific community’s technical communication methods and the indigenous peoples’ — they don’t use papers, numbers and theories. In Cobra’s groups, participants use drawings, photographs and videos to register their ideas.

While the Cobra project is criticised by anthropologists because of the technological resources they bring to traditional groups, Berardi said “this does not make them less indigenous”.

After producing the visual materials they go to other communities in the region to share their experiences on how to solve local problems, creating dynamic network. The videos and images are also available on a website.

Berardi believes this approach — where the solutions are locally sought, locally executed and have local beneficiaries — will have a positive long-term effect on the Guiana shield’s social and ecological environment. The fact that they are sharing ideas with other indigenous groups — and not with “pale, male scientists” — has a great impact, Berardi told me.

He also highlighted the importance of having a holistic view of indigenous problems. They are not isolated from each other, but are a complex combination of environment, health, social and other issues that demand complex and combined solutions.

Projects like this, however, face a lack of acceptance in the scientific community. “There is a clear conflict between the principles behind Cobra’s participatory, visual and systemic approach, and the demands of policymakers for ‘scientifically’ validated communications, which require an imposition on the type and process of data collection, analysis and positioning in the public sphere,” says Berardi

But he believes his team’s efforts are worth it. New solutions for global problems can emerge from local experiences, he said.