By: Nick Kennedy

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The only guaranteed way to end the AIDS pandemic lies in developing an HIV vaccine because cultural barriers and the weakness of human nature hinder efforts to control the disease using non-vaccine prevention, leading experts have said.

“There have been a number of articles recently suggesting that we are near the end of the AIDS epidemic, which is pretty bold and pretty risky to say without a preventative HIV vaccine,” says Gwynn Stevens, head of the International Aids Vaccine Initiative’s Southern Africa programme.

And although non-vaccine prevention has led to a dramatic reduction in new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths, behavioural, cultural and legal barriers are impeding the success of such efforts, according to a paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine last month (6 February).

Human behaviour is the greatest challenge to non-vaccine prevention because this technique requires consistent individual action and “human nature is weak”, says Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the United States, and paper co-author.

“There have been a number of articles recently suggesting that we are near the end of the AIDS epidemic, which is pretty bold and pretty risky to say without a preventative HIV vaccine.”

Gwynn Stevens, International Aids Vaccine Initiative

An existing intervention such as preexposure prophylaxis, which involves giving medication to people who are not infected with HIV to reduce their risk of catching the disease, works when people stick to it, Fauci tells SciDev.Net.

“But even though many people know it works, they don’t adhere,” he says.

Cultural and legal issues also hinder the success of non-vaccine prevention, the paper says. For example, in the more than 70 countries where homosexuality is illegal, it is hard to reach homosexual men, one of the major target groups, for counselling and treatment, says Fauci.

Stevens says: “You’re never going to get somebody to come and get tested when they are threatened with jail or even the death sentence.”

Most recently, for example, Uganda’s decision to further criminalise homosexuality — and purport to use scientific evidence to support the move — has caused uproar in the aid and human rights communities.

The paper’s authors add that cultural factors have probably slowed rates of male circumcision, which can reduce the risk of HIV transmission from women to men by 60 per cent.

In 2007, public health officials from 14 countries in southern and eastern Africa began a campaign to carry out 20 million voluntary male circumcisions across the region, but less than a quarter of the 20 million target have undergone the procedure.

“Uptake has been slow, but it’s really increasing very significantly, particularly over the last couple of years. We need to increase and sustain our efforts there,” says Rachel Baggaley, who works for the WHO’s HIV prevention team.

She adds that, given the complexity of human behaviour, blaming weak human nature for poor non-vaccine intervention outcomes is “a very simplistic way of putting it”.

However, in terms of vaccine research and development, Fauci says that significant recent progress promises impending breakthroughs.

“Developing a vaccine is still a major scientific challenge, but there have been some really important insights over the last year or two,” he says.

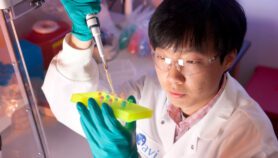

In 2012, the effectiveness of an HIV vaccine called RV144 against infection was confirmed. The vaccine’s — albeit modest — impact was first demonstrated in a trial in Thailand in 2009.

“The RV144 trial was really the first proof of concept that an HIV preventative vaccine, although very moderate, can actually prevent infection,” says Stevens.

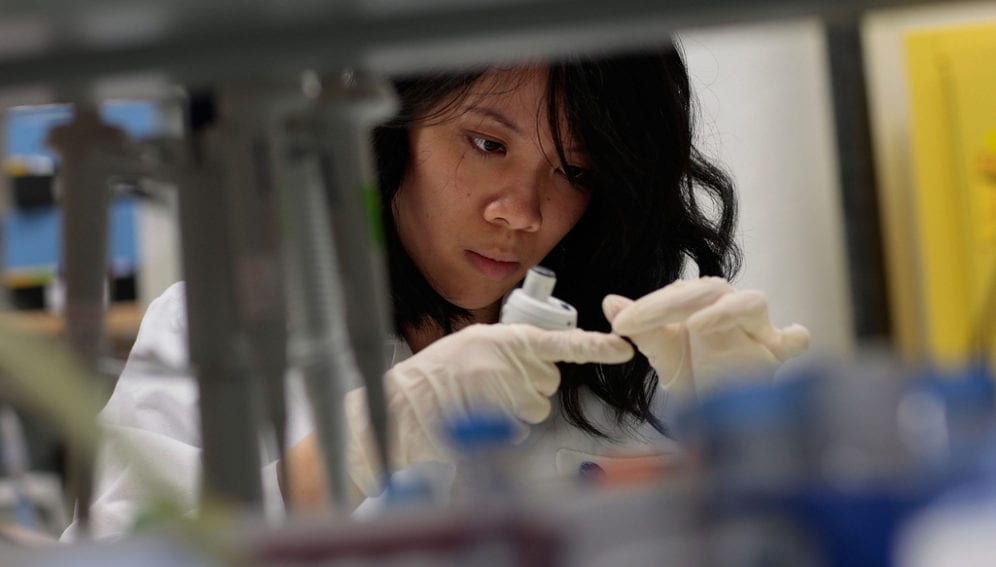

And scientists have also found that a group of human antibodies, called broadly neutralising antibodies, can inhibit the effect of a wide range of HIV strains in a test tube. Researchers are now starting to understand what characteristics of the virus drive the production of these antibodies, so they hope to eventually be able to induce their production in non-infected people, Fauci tells SciDev.Net.

Link to article in The New England Journal of Medicine

References

The New England Journal of Medicine doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313771 (2014)