Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The future of a WHO programme that ensures the quality of medicines for numerous global health NGOs and UN agencies is vulnerable unless more donors start funding it, health experts have warned.

The Prequalification of Medicines Programme (PQP) relies on just two donors — the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and global health organisation UNITAID — for roughly 90 per cent of its funding.

This situation could spell the programme’s demise should either donor end its funding, according to an article published in the Journal of Public Health Policy last month (16 January).

“The importance of the work of PQP, coupled with the fact that its funding base is not solid enough, potentially creates a very risky situation,” says Ellen ‘t Hoen, the paper’s lead author and a consultant on medicines law and policy.

Launched in 2001, the programme was initially developed to address the lack of affordable antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for people infected with HIV in developing countries.

In 2000, only one HIV patient in a thousand had access to ARVs in Africa, according to statistics cited in the paper.

“The situation was dire,” says Joep van Oosterhout, who is medical and research director for the NGO Dignitas International and who has worked in Malawi since 2001. “A few patients were able to start treatment, but, generally, could not afford to continue. Even though they were subsidised by the government, the drugs were still far too expensive for the vast majority of people.”

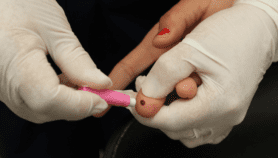

The WHO set up PQP to verify the quality of generic ARVs that Indian drug firms had recently brought onto the market. By ensuring drug reliability, the programme enabled bodies such as the Global Fund to make cheap ARVs widely accessible through grants to developing countries.

PQP saved public drug procurement agencies, such as the Global Fund and national governments, US$170 for every dollar that donors put into the programme as a result of cheaper generic drugs of known quality being available, according to 2009 statistics cited in the paper.

Charles Clift, a senior consulting fellow at UK policy institute Chatham House, says: “[PQP] was certainly a very important factor in bringing down the price of some medicines and promoting their availability in a wide range of developing countries, which otherwise probably wouldn’t have happened.”

Over three quarters of the eight million people being treated for HIV in 2012 were receiving ARVs that had been prequalified by PQP, according to the paper.

Clift agrees that relying on two donors for the bulk of funding leaves PQP in a precarious position.

“There are risks in any [funding] system, but being reliant on two donors means that there would be immediate consequences if either change their mind about investing,” he says. “It would be serious if the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation withdrew funding, but if UNITAID withdrew funding, that would be the end of it.”

UNITAID currently contributes US$11 million of PQP’s annual US$15 million budget.

Without the programme, ineffective drugs could find their way onto markets that have little regulatory oversight, says ‘t Hoen.

“If low-quality drugs get into the system, there is a risk of the development of drug resistance as well as people just not receiving the amount of active ingredients needed,” she says.

A broader donor base is also needed to expand PQP’s mandate to cover new drugs used to treat cancer and hepatitis C, she adds. These are not priorities for the programme’s current donors, but are growing public health concerns in many developing countries, according to ‘t Hoen.

While a scheme to help cover some of PQP’s costs by charging drug manufacturers a fee was recently implemented, ‘t Hoen believes this will eventually lead to higher drug prices. She suggests governments and others pick up the tab instead.

“If all the agencies, organisations and governments that spend money on the procurement of these drugs — and that benefit hugely from the programme — would split the bill [for PQP] among themselves, they would all end up with a very small charge,” she says.