Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Typhoid fever bacteria can live on gallstones in people who carry the disease without showing any symptoms, scientists have found.

This could explain how the disease — which causes fever, headache, nausea, loss of appetite and diarrhoea — continues to be spread despite having no environmental reservoir.

It has been known for decades that Salmonella enterica typhi can accumulate in the gallbladders of people who have recovered from typhoid fever – and sometimes in people who have never experienced any symptoms.

Antibiotics tend to be ineffective against chronic typhoid infection and gallbladder removal is a common treatment.

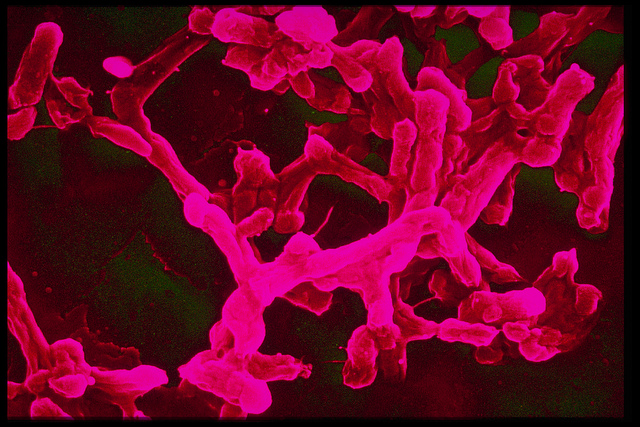

Research published by Mexican and US scientists in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last month (22 February) suggests that the bacteria collect in 'biofilms' — communities of microorganisms — on gallstones (stones that form, often harmlessly, in the gallbladder). This may explain how the disease persists and spreads.

The authors observed the formation of biofilms in gallstones of mice infected with a version of typhoid fever and found that they had more Salmonella typhi in their gallbladder tissue, bile and fecal matter than gallstone-free mice.

These biofilms were also observed on the gallstones of patients in Mexico City — where typhoid is common — who were found to be carrying typhoid when they had their gallbladders removed.

John Gunn, professor of molecular virology, immunology and medical genetics at Ohio State University in the United States and one of the authors of the study, told SciDev.Net that much of the human-to-human spread of typhoid was due to chronic carriers and eliminating this transmission "could save untold lives worldwide".

He said the next step was to identify the bacteria's 'Achilles' heel' by understanding how they bind to gallstones and how the bacteria interact with each other to form a stable community.

Gunn said this could lead to the development of treatments that could both prevent biofilms from forming and make existing biofilms disperse.

The WHO estimates that about 17 million people contract typhoid fever each year, and the disease is a particular problem in parts of the developing world with poor sanitation.

Gunn said that while public health measures such as clean water and sanitation are key to controlling typhoid fever, eliminating chronic infection "could significantly decrease the suffering due to typhoid fever in the developing world".

Link to abstract in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences*

* free access to users in developing countries