By: Inga Vesper

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Syria’s outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis — a parasitic infection that causes skin lesions — is not caused by the corpses of infected people being dumped in the open, a paper points out.

The study corrects misinformed reports in Syrian and international media, which wrongly said the disease was transmitted through the bodies left on the streets in Syrian villages by the extremist group Islamic State (IS).

In December, the group executed people in villages rebelling against IS rule and dumped corpses with visible skin lesions in the open, saying that the disease would infect locals as a punishment for their insubordination.

But in their paper, published yesterday in Cell, researchers say that this non-deadly form of leishmaniasis can only be transmitted through the sandfly that carries the parasite biting living people.

“This kind of alarmist news serves only to propagate fear and stigmatise those suffering the disease,” says coauthor Karina Mondragon-Shem, a parasitologist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the United Kingdom.

After five years of civil war and occupation by IS, Syria’s health system is in meltdown, the researchers write. The number of known leishmaniasis cases doubled between 2008 and 2012, when around 53,000 cases were registered, the paper says.

But the true figures may be much higher, since official efforts to monitor the disease were abandoned in 2012 after Aleppo, the home of Syria’s leishmaniasis control programme, fell to ISIS, the authors say.

“Structures across the country have been demolished, the whole health system has collapsed and health staff are scarce or altogether absent in some areas,” says Mondragon-Shem. “The urgency of war casualties does not leave a place for [fighting] a stigmatising disease such as leishmaniasis.”

Cutaneous leishmaniasis — which is distinct from the rarer, more severe visceral leishmaniasis — is controlled by using bednets and treating people before the lesions break out.

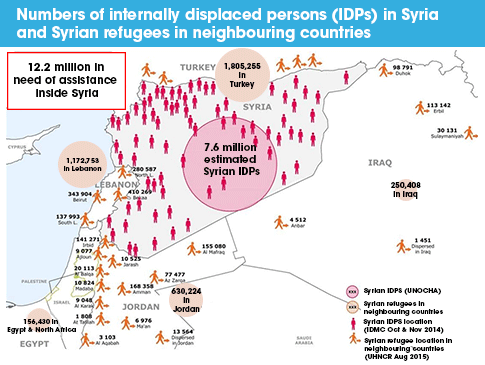

But the lack of resources in refugee camps within and around Syria makes it difficult to control leishmaniasis, and refugees are bringing the disease to areas where it was previously nearly eradicated.

Alsalem explains that sandflies find plenty of breeding sites near sewage canals and among uncollected rubbish in refugee camps and in Syria’s war-torn cities.

“But it is important to underline that leishmaniasis cannot be spread by IS,” he says. “It is only the presence of sandflies that makes it possible for the disease to be transmitted.”