By: Lisbeth Fog

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[BOGOTA] A row is simmering in Colombia after an animal research centre in the Amazon was shut down following allegations of “monkey trafficking”, leaving local scientists worried about research being stifled.

Last April, more than 100 scientists from research groups in Colombia issued an open letter stating that the country’s ability to innovate had been “paralysed” after the state court’s decision to close the Primates Station of the Immunology Institute-Foundation of Colombia in Leticia.

The centre hosted a long-running programme that involved testing malaria vaccines in monkeys captured from the wild.

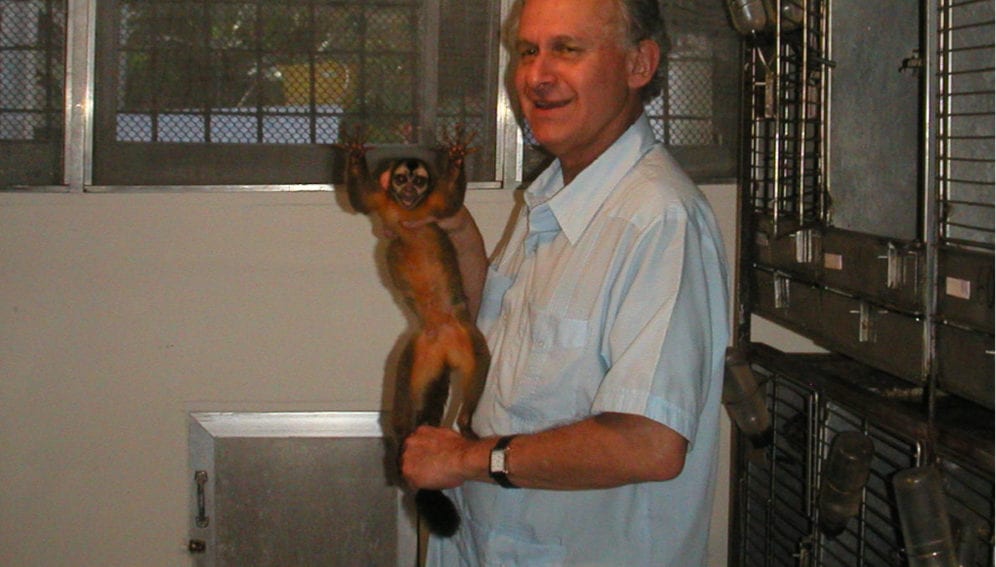

The saga started in April 2011 when Colombian conservationist group Entropika, led by Angela Maldonado, filed a lawsuit against Manuel Elkin Patarroyo, an immunologist who founded the centre.

Among other things, Patarroyo was charged with allowing lapses in the animals’ wellbeing and breaching his licence conditions — which only allow the use of Colombian monkeys — by using monkeys from neighbouring Amazonian countries.

There were some “strange events and irregularities” at the centre, Maldonado tells SciDev.Net.

For example, she says, freedom of information requests by Entropika showed the centre took in 920 monkeys in one three-month period in 2012 while its licence only allows the use of 800 a year.

These results were published in the American Journal of Primatology in February, but Maldonado says the Colombian environmental ministry did nothing about it.

Entropika was also worried about the sustainability of using wild monkeys. It says its studies show that the type of owl monkey the lab used are declining in number and could be endangered.

Monkey business

Before the ruling, the centre had been using about 800 monkeys a year, Patarroyo told Colombia’s El Tiempo newspaper in April. He said that the animals were supplied by indigenous people, who were paid about US$40 for each monkey they trapped.

The research centre then tested potential malaria vaccines on the animals.

According to Patarroyo, if the monkey did not contract the disease after being injected with the parasite it would be returned to the wild once scientists had evaluated the possible causes. The procedure was to place the monkey in quarantine and then release it at the site in the jungle where the seller reported it had been captured. If the monkey did get sick, it was treated with drugs and then a similar release protocol was followed.

Patarroyo’s research group has been using this method of vaccine development for more than three decades. In a separate interview with El Tiempo last December, he insisted that no more than five per cent of the monkeys he uses die — about 40 animals a year.

Nonetheless, following the lawsuit, the courts ordered the centre to create its own primate breeding programme, so it can stop using wild monkeys.

It must also meet several other requirements before it can apply for a new licence, including reducing the overall number of monkeys used and restricting experiments to the native Colombian species, Spix’s owl monkey (Aotus vociferans), while avoiding the Peruvian red-necked owl monkey (Aotus nancymaae), which lives in Brazil and Peru.

A complicating factor is a study of the distribution of Aotus nancymaae monkeys released by the National University of Colombia in July. This shows that these monkeys are also found in Colombia — though Maldonado claims this may be because the research centre introduced them to the area.

Arguments rumble on

It is these court demands that have raised the ire of the Colombian scientists who wrote the letter. Although they recognise Maldonado’s right to be concerned about animal testing, they say it is “very shabby and worrying” that the state court revoked the centre’s licence without consulting the scientific community or considering its impact on the country’s scientific research.

Ivan Dario Velez, a parasitologist at the Univeristy of Antioquia in Colombia who spearheaded the letter, told SciDev.Net that it was not right that the court listened to the environmentalists, but ignored scientists’ arguments.

Yet Enrique Gil Botero, the judge in charge of the case, tells SciDev.Net: “We are not forbidding research. [The government] can issue the licence again, provided Patarroyo meets the law.”

He adds that the scientists behind the letter cannot have read the judgement properly because their conclusions about research being stifled are based on a premise that does not correspond to the text of the judgement.

Patarroyo refused SciDev.Net’s requests for comment.

> Link to the court ruling against Patarroyo (in Spanish)

> Link to paper abstract in American Journal of Primatology

> Link to the scientists’ letter (in Spanish)