By: Geoffrey Giller

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

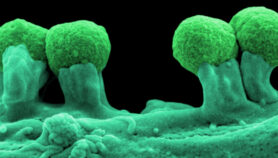

Researchers have sequenced the genome of a rare, ten centimetre-long, ribbon-shaped tapeworm that had been travelling through a man’s brain for four years in a move that could lead to new treatments for tapeworm infections.

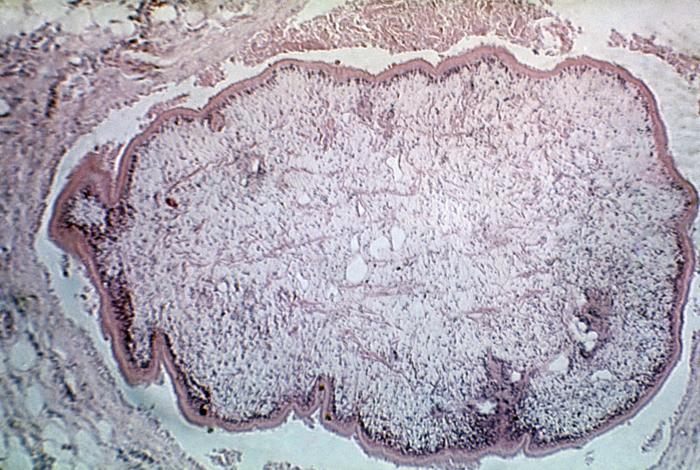

Tapeworms usually infect the gut, causing symptoms such as weakness, weight loss and abdominal pain. But the larvae of some species can reach the eyes, brain and spinal cord. The species in this case, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, is one such parasite.

Human infections caused by the larvae from this and closely related species are known as sparganosis. Although these species are found worldwide, such medical cases are most common in Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea and Thailand.

Other tapeworm species have a greater worldwide impact, for example causing neglected tropical diseases such as seizure-causing neurocysticercosis and potentially fatal alveolar echinococcosis.

In the case at the heart of the new research, a man of Chinese ethnicity living in the United Kingdom but who frequently visited China sought treatment in 2008, complaining about headaches, seizures, memory loss and occasional episodes of altered smell.

An MRI scan showed small lesions in the man’s brain. However, numerous tests for everything from HIV to tuberculosis came back negative.

Doctors monitored the lesions for four years and found something strange: they moved around. Only when doctors operated on the man in 2012 did they discover the ten centimetre-long tapeworm

living in his head.

The reason it took so long to diagnose, says Hayley Bennett, a researcher at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, United Kingdom, and the lead author of a paper on the research published last week (21 November) in Genome Biology, is that infection by this particular type of worm is exceedingly rare.

“That was the first time this worm has ever been seen in the UK,” she says. “I think the clinicians were pretty surprised.”

“The genome represents the first of this order of tapeworms to ever have been sequenced.”

Hayley Bennett, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

From 1953 to 2003, scientists have only documented about 300 cases worldwide of infections by the tapeworms that cause sparganosis. Typically, infection occurs by eating infected animals such as frogs or snakes or by drinking contaminated water.

The genome represents “the first of this order of tapeworms to ever have been sequenced,” says Bennett. “By looking at all different tapeworm species, we can understand more about the biology, what’s common, and what’s important to the tapeworm.”

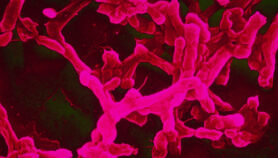

The team also discovered that one of the drugs most commonly prescribed for tapeworm infections would fail to treat this particular worm because of mutations in some of its genes. “It’s important to sequence rare tapeworms,” says Bennett, because it may show how drugs developed for more common infections can be adapted, potentially leading to new treatments.

“I think this paper has an impact on the study of sparganosis,” says Urusa Thaenkham, a parasitologist at Mahidol University in Thailand. “I think we can follow their analysis methods to determine drug targets for the common tapeworm infections.”