12/06/20

Brazil drives increase in worldwide forest loss

By: Pablo Correa

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[BOGOTA] Primary forest destruction contributed carbon dioxide emissions equivalent to 400 million cars last year, as tree cover loss increased by 2.8 per cent compared with 2018.

Primary forests located in the tropics are especially important for carbon storage and global biodiversity. Last year the tropics lost 11.9 million hectares of tree cover, according to analysis by the online monitoring platform Global Forest Watch (GFW).

Analysts warn that despite efforts to halt deforestation and apparent successes by some countries in curbing forest loss, “the 2019 data underscore one fact: the fight to curb tropical forest loss is far from over”.

“Though the overall trend in primary forest loss across the tropics is worrisome, some countries have shown that it is possible to reduce forest loss through sustained action.”

Mikaela Weisse, Global Forest Watch

The Food and Agriculture Organization says a primary forest is a naturally regenerated forest of native species, where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed.

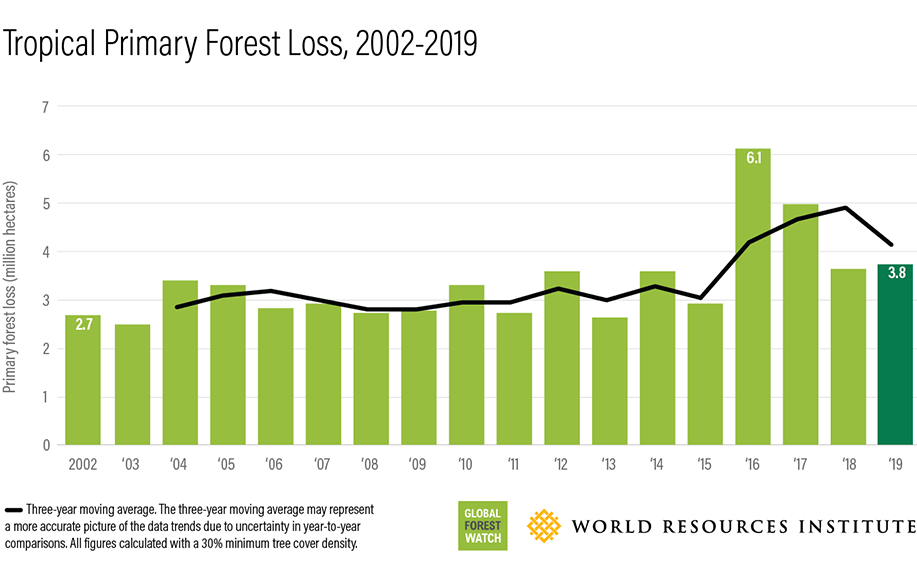

While the data from the University of Maryland shows the rate of tree cover loss did not reach the record figures of 2016 and 2017, it is still the third highest annual toll in 20 years, GFW analysts Mikaela Weisse and Elizabeth Dow Goldman say.

Tree cover loss is not the same as deforestation — the total destruction of trees — as it encompasses the removal of tree canopy due to human or natural causes, including fire.

Nearly one third of the loss, 3.8 million hectares, occurred within humid tropical primary forests. The loss is the equivalent of losing a primary forest the size of a football pitch every six seconds, or an area equivalent to Switzerland every year, the analysis says.

Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire in West Africa, conversely, reduced primary forest loss by more than 50 per cent compared with 2018.

Top ten

Brazil suffered the highest loss of primary forest of 1,361,000 hectares — more than a third of the total loss of humid tropical primary forests worldwide — followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with 475,000 hectares and Indonesia with 324,000 hectares. Indonesia’s loss, however, was lower than the previous year by five per cent.

“Aside from 2016 and 2017, which faced widespread losses due to understory fires, 2019 was Brazil’s worst year for primary forests in 13 years,” Weisse tells SciDev.Net.

In the case of DRC, most losses appear to be related to agriculture, but there is emerging evidence that some may be tied to large-scale commercial logging, mining and plantations, the analysis notes.

Other most-affected countries include Bolivia, Peru, Malaysia, Colombia, Laos, Mexico and Cambodia.

Global Forest Watch was created in 2014 by the World Resources Institute, Google and more than 40 partners, and produces high-resolution digital maps updated by Google and scientists at the University of Maryland using NASA satellite imagery.

Amazon loss

According to the data, one particular form of forest loss — clear-cutting forests for agriculture and other new land uses — rapidly increased in the Brazilian Amazon in the past year.

“Several things indicate that there is a deep change in forest protection policies in Brazil,” Paulo Moutinho, a senior researcher from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute, tells SciDev.Net.

“Government agencies dedicated to the protection of forests are being dismantled, torn apart. The president [Jair Bolsonaro] says we have to cut forests to ensure the country's progress. The vision is the same as we had 30 years ago. This is a very big setback to protection policies,” says Moutinho, who did not participate in the GFW analysis.

The analysts say they detected “troubling” new hotspots of deforestation within indigenous territories of the Amazon due to illegal land-grabbing.

Protection

Brazil’s neighbour Bolivia also experienced record-breaking tree cover loss. The country’s total loss in 2019 was more than 80 per cent greater than in 2018, which GFW attributes to a combination of climatic conditions that favoured the spread of fires, and human activity, especially large-scale agriculture.

Among the countries of the Amazon basin, Colombia showed signs of curbing forest loss.

Deforestation increased following the signing of the 2016 peace agreement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which controlled remote rainforest areas.

The Colombian government’s policies may be leading to a reduction of land clearing for colonisation and cattle ranching. These actions include the conservation programme Vision Amazonia, which has the financial support of European countries, and a military strategy focused on the points of greatest deforestation.

Data

According to Ederson Cabrera, in charge of the national deforestation monitor system at Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Ideam), the GFW data is helpful for identifying trends, but less so for absolute values in each country.

For Colombia, the estimation difference can be about 20,000 hectares, he tells SciDev.Net.

Pablo Negret, a researcher at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland, Australia, agrees with Cabrera.

"The Global Forest Watch data is very useful since it is freely available. However, it is often imprecise,” Negret says.“I would recommend using national information if it is available when you are going to do analysis on this scale or less.”

For Moutinho, despite the bad news about Brazil, there are reasons for optimism.

“We already halted deforestation between 2005 and 2012, when we reduced it by up to 80 per cent,” he says. “We know the elements that are needed to eradicate deforestation.”

Weisse is also optimistic: “Though the overall trend in primary forest loss across the tropics is worrisome, some countries have shown that it is possible to reduce forest loss through sustained action.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America & Caribbean desk.