By: Kate Hawley

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Kate Hawley examines how urban areas are evolving to be sustainable — their challenges, trends and solutions.

Already, 54 per cent of the world’s population lives in urban regions, and projections suggest this will keep increasing until at least 2050. [1] The shift from a rural- to an urban-dominant globe signals more strongly than ever the need to transform how cities develop. Architects, engineers, urban planners, civil society and policy makers face the challenges of creating sustainable, healthy, ‘smart’, ‘green’, adaptive, inclusive, productive, safe, flexible and resilient cities. These are just a few of the characteristics that will help urban centres thrive in the face of rising populations, growing informal settlements, pollution and environmental degradation, often combined with poor governance and service provision.

Some cities around the world are pioneering the way, helping the development community envision alternatives to mainstream models of urban development, and focusing on creating environmentally friendly ‘cities for the people’, rather than economic growth. This Spotlight shares innovative thinking in urban planning, urban design, and urban technology to highlight some of the transformative solutions that are shifting the way the world views cities.

Sustainable thinking for cities evolves

Research and thinking about sustainable cities began in the 1980s, but the term sustainability entered the global dialogue in the 1990s, introduced by the World Commission on Environment and Development. [2] In particular, the crucial role that environmental and social dimensions of human economic activities play in creating a better world surfaced during the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. [3] Influencing those discussions, an agenda-changing report, authored by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature) and UNEP (the UN Environment Programme), highlighted how humans construct landscapes at the expense of the environment — and urged a focus on sustainable development. [4]

As the sustainability discourse evolved, definitions and characteristics of ‘sustainable cities’ began to take form. In the late 1990s David Satterthwaite, a key expert in the field, put forward characteristics of a “successful” city. [5] He argued that a city needs to ensure healthy living and working environments, and provide infrastructure for basic services such as clean water, sanitation and waste management. He also argued that — in keeping with the basic principles of sustainable development — a city needs to exist in an equilibrium with environmental systems, for example by ensuring balanced water tables and low environmental pollution.

The definition of sustainable cities continued to grow after the 1990s, incorporating ideas on how resources might be used now without compromising their future availability. [6] Some suggested all cities must meet the needs of their residents in order for any city to be truly sustainable. [7] Yet, the definition of what makes an area urban is still elusive — cities have many varying characteristics. Areas can be classified as urban based on: population thresholds (above a certain number of people); human densities (human count per square meter); employment proportions (those employed in the agriculture sector compared to service industries); or the existence of typical urban services like piped water, electricity and educational and health facilities. [8]

Discussions on urban sustainability then began to include spatial design and planning (known as ‘urban form’), and making cities ‘user-friendly’ through transport systems that are accessible to all. [9] Through this, definitions of urban form became more detailed — referring to dense, compact, mixed-use spaces with integrated public transportation, environmental policies and management. [10] During preparatory meetings for the URBAN21 Conference (July 2000), one of the first global conferences dedicated to urban issues, urban sustainability was defined as “improving the quality of life in a city, including ecological, cultural, political, institutional, social and economic components, without leaving a burden on the future generations”. [11] Just a few months later, the millennium development goals (MDGs) were adopted, incorporating an environmental sustainability goal. In 2005, the World Summit on Social Development introduced the concept of economic, social and environmental ‘pillars’ of development. Now, as the post-2015 agenda develops to supersede the MDGs, negotiations are underway to secure a spot for an urban Sustainable Development Goal (Goal 11 in the current SDG draft) that will ensure green, well-planned, inclusive, resilient, productive, safe, and healthy cities.

Urban trends

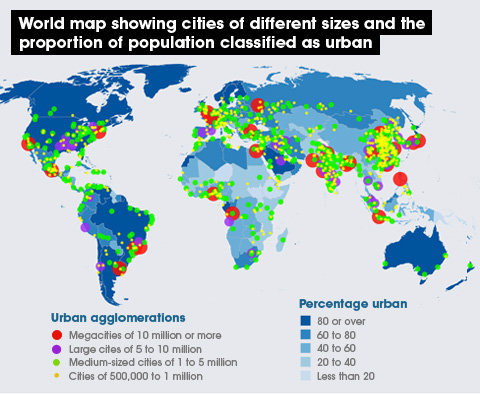

The world’s urban population stands at 3.9 billion people. More than half of them live in ‘small’ cities with less than 500,000 people, while approximately 12 per cent reside in megacities (of over 10 million). [1] Figure 1 shows how different sized cities are distributed across the globe. By 2050, an estimated two-thirds of the world’s population — about 6.2 billion people — will live in urban centres. [1] In other words, we will see urban growth (rising urban populations) and urbanisation (a higher proportion of people will live in cities). [8]

-

Megacities: 10 million or more

-

Large Cities: 5 to 10 million

-

Medium Cities: 1 to 5 million

-

Small Cities: 500,000 to 1 million

Adapted from the UN’s World Urbanization Prospects [1]

Defining city size by population

African and Asian cities have grown faster since 2000 than cities in any other part of the world (Figure 2). And more than half of these continents’ populations are expected to live in cities by 2050. And by then, India, China and Nigeria alone are expected to add 2.5 billion people to their urban areas. [1]

Interestingly, the fastest growing urban settlements are not the megacities that so often hit the headlines, but the medium-sized and smaller cities that house less than 1 million inhabitants [1]. By 2025, megacities will have accounted for just 10 per cent of global urban growth. Medium and large cities will contribute to more than half of global growth, followed closely by small cities. [12]

Most medium and small cities will be in low- and middle-income countries. And they often face different sustainability challenges to megacities — overall, for example, poverty rates may be higher and the challenges might relate more to the efficiency rather than availability of basic services. [1,13,14]

Growth drivers and challenges

Urban growth is mostly fuelled by natural population growth and rural-to-city migration. [8] Migration is driven primarily by economic incentives such as trade, but also the search for a better quality of life.

Alongside the pressures of rising populations, cities face numerous environmental and socio-economic challenges (see Box 1).

Informal settlements (slums) that often occupy areas just outside the city centers (peri-urban locations) are arguably a unique feature of cities in the developing world. Around one in seven people — a total of 1 billion — live in informal settlements and self-built homes; this number is expected to reach 3 billion by 2050. [13] Slum dwellers face distinct challenges such as insecure land tenure and unsafe housing. Public services such as electricity grids or sanitation infrastructure do not reach them. This, and close living quarters, increases their risk of infectious diseases. [15] However, slums are also hubs for self-employment, community development and innovation.

Box 1: Urban growth challenges: key facts

- Poverty

- Urban poverty (people living on less than US$1 day) has grown by 13 per cent in the past 10 years, so that 28 per cent of urban residents are now said to be living in poverty. [16]

- Energy

- In most low- and middle- income nations, around 30 per cent of city dwellers lack access to electricity or heating fuels. [17] Energy use in growing cities is intensive across several sectors including power and heat, transport and solid waste.

- Food

- People living on low incomes in urban areas must usually buy their food, and are particularly vulnerable to fluctuating prices. For example, in 2003 in Tanzania, local food prices jumped by 81 per cent of the change in the global corn price. [18]

- Transport

- Traffic congestion is a longstanding challenge for urban areas in developing countries. Apart from causing mobility problems, it damages human health: traffic-related air pollution is linked to a higher risk of death from respiratory and cardiovascular disease. [19] And 91 per cent of the world’s road crashes occur in low-income and middle-income countries, even though fewer people own cars than in developed countries. [20]

- Solid waste

- Municipalities in developing countries often spend up to half of their budgets on waste management. Still, it’s not unusual for 30-60 per cent of solid wastes to be left uncollected, and for solid waste services to reach less than half of the population. [2122] Poor management leads to pollution and disease.

- Water and sanitation

- Poor drainage of sewerage and other waste water leaves many people living in polluted environments. The WHO has estimated that 2.4 billion people will still lack access to improved sanitation systems in 2015. [23]

- Health

- Pollution favours disease transmission through air, water and insect vectors. Respiratory, gastrointestinal and skin infections are common in urban areas. [21] Chronic diseases such as obesity often also accompany urbanisation as peoples’ lifestyles change.

- Climate change

- The largest share of greenhouse gas emissions comes from urban areas — about 70 per cent globally. [24] But cities in developing countries contribute only a small share, because residents tend to use less energy-intensive resources. The World Bank estimates that globally, US$80-100 billion per year of climate adaptation costs will occur in urban areas [25,26].

- Disaster risk

- Urban areas tend to attract vulnerable populations and are often poorly equipped to deal with disasters and extreme events. [24,27,28]

- Housing

- Globally, one billion people — most in developing countries — live in inadequate shelters. Problems such as insecure land tenure, poor construction skills and limited access to financial mechanisms bring shortages of affordable, safe housing. Most people on low-incomes add to their homes incrementally through informal financing — but tend to build structures that are vulnerable to disasters. [29]

Innovative urban planning

To meet these challenges, some cities in the developing world are transforming and pioneering innovative planning, integrative design and use of technology. Whether they are called sustainable cities, eco-cities, low-carbon cities, ‘smart’ cities or zero-energy cities, they strive for a safe and healthy environment for all residents. And they share key characteristics of sustainable development: reduced energy use, minimal encroachment on ecological spaces, fewer harmful building materials or more closed-looped systems to manage waste. [30]

All these cities place importance on policy, programming and planning. So, how does urban planning create a sustainable city?

The prospect can seem overwhelming. But solutions can be big or small. Determined leaders in the Global South, as well as influential architects, engineers and civil society organisations can drive change. For example, some cities are aiming for low-carbon emissions — whether by developing high-tech greenhouse gas inventory systems to track emissions, or by creating ‘green’ and ‘walkable’ neighborhoods through participatory planning. In the United Arab Emirates, the cities of Dubai and Masdar are integrating green space, ‘net-zero’ emissions goals, water reuse systems and urban agriculture. [31,32] In Nairobi, Kenya, communities are using modern technologies to map slum areas, helping planners and politicians see how to provide better services. [33] In some cases city leadership has shifted to encompass experts such as engineers, architects and urban planners, bringing technical knowhow to bear on their vision of sustainability (Box 2).

Box 2. Jaime Lerner and the transformation of Curitiba |

Jaime Lerner became Mayor of Curitiba, Brazil in 1971. Over three elected terms he transformed Curitiba into an example sustainable city that continues to inspire. An urban planner by trade, Lerner was the first non-politician to become mayor and brought technical expertise to the post — now a more common qualification in the city’s political leadership. Curitiba was first to introduce a Bus Rapid Transit system (BRT), which has since been widely adopted. And it took ‘human-ecology’ approaches to urban sustainability, creating 52 square meters of green space per person. [34]

But perhaps the most transformative solution was to include migrants and their informal settlements in city planning. In the early 1990s Curitiba had 209 slums — representing one-ninth of its population. The city instituted a garbage purchase programme, where small trucks traverse the narrow roads of informal settlements collecting garbage and recyclables at designated locations. Residents can exchange their garbage for tickets they can swap for food and other supplies (for example, two kilos of recyclables will earn enough tickets to obtain a kilo of food). To cope with continuing inflow, the city also developed a new area to house up to 30,000 migrants. Because many migrant families had construction skills, the city provided each with a plot of land, title deeds to it, building materials and access to experts for construction advice. This type of planning created better living standards because people felt ownership for their land, and the uniqueness of each house became an expression of people’s creativity and resourcefulness. |

Integrative urban design

Integrative design, which focuses on optimising whole systems instead of a single component, is becoming more prominent. Transport systems might integrate bike paths, bus routes and rail lines; or new building constructions may integrate site planning with local materials and energy and water-reduction systems; or even building designs that mimic natural processes (Box 3). The city of Bogota, in Colombia, is a good example of how integrating mobility strategies into urban design can boost a city’s sustainability credentials (Box 4). In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, a BRT system is under construction, with high-capacity low-carbon buses planned for the urban transport mix. The buses will be quieter, cleaner and more fuel-efficient than traditional buses — and able to carry about 100 more passengers. [35]

Box 3. Integrated mobility in Bogota |

|

Enrique Penalosa, elected Mayor of Bogota in 1998, devised an ‘integrated mobility strategy’ to tackle the city’s massive traffic congestion — starting with a BRT system, the TransMilenio. Launched in 2000, its four lines stretch 55 km over the city. It is the first-ever mass transit system for Bogota. TransMilenio buses run three times as fast as a typical New York City bus and carry 36,000 persons in each direction per hour. [36]    But the BRT was just the start. Since the city’s expensive railways were no longer needed, the money put aside for them funded 350 kilometres of protected bikeways developed using a design strategy called ‘ciclorutas’. This strategy integrated bikeways into a mixed land-use pattern. A bike network connected main city neighbourhoods; then a secondary bike network connected to the main city network, supported by a third bike network completing a mesh design. In 2005, Bogota received the first ever Sustainable Transport Award from a consortium of experts and organisations working on sustainable transport, recognising its reclamation of public space for citizen use. |

Integrative design is also starting to take hold as a way for the developing world to attack challenges that countries in the North do not face. It offers opportunities for the South to lead with innovation, and by including many stakeholders in the process. [37]

In 2013, a resilient housing design competition, hosted by ISET-International and Hue University in Da Nang, Vietnam, charged architects, planners, and engineers with designing an integrated housing system that could withstand the annual typhoons that hit central Vietnam’s coast (and which are expected to be more frequent and intense with climate change). [38]

The designs combined site planning, building design, and construction technology. They incorporated two fundamental elements of typhoon-resilient housing: that all structural building parts are connected by reinforced concrete beams and pillars; and that each house has a ‘safe failure room’, made with reinforced concrete, that offers an emergency shelter during calamitous typhoons. The designs also took into account settlement patterns, for example nonparallel or zigzagging roads to reduce wind pressure on buildings. And they used simple building forms as well as pitched roofs to lower typhoon risk.

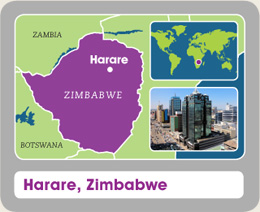

Box 4. Biomimicry: copying nature’s integrative design |

|

Biomimicry is a new scientific approach to building design that utilizes nature as a model, measure and mentor to solve complex human problems. [39] In Harare, Zimbabwe, an office and shopping complex has been designed by mimicking self-cooling African termite mounds. Termites build elaborate mounds in which they tend their food — a fungus which requires a constant temperature of 30.5 degrees Celsius to survive despite outside temperatures that can vary from below 4 degrees to above 38 degrees Celsius. The termites open and close heating and cooling vents as needed.    Vents can suck air through tunnels or enclosures in the muddy walls, damping down the temperature fluctuations before the air reaches the centre of the mound. The office complex in Zimbabwe copied this process to design a ventilation system where the mass of the building either cools or heats the air, regulating the internal temperature. The building uses 10 per cent less energy than other similar buildings, saving over US$3 million in energy costs that would have been incurred by installing an air conditioning system. [40] |

Urban technologies

Technology has transformed ways to monitor, manage and design urban systems such as those for traffic and water. The most successful technologies have been combined with programmes that encourage their use, offering city-wide or small-scale tools that promote sustainability. But sometimes such systems are costly, and may not necessarily suit the average quickly-urbanizing city (see Box 5).

In the Caribbean, just outside of the capital city of Port-au-Prince, sits Haiti’s first sewage treatment plant. Port-au-Prince is one of the world’s largest cities without a sewage system. This treatment plant, introduced four years ago and funded by donor agencies, operates differently to others in the developing world — trucks collect sewage from private septic pits, latrines and canals. That cost significantly less than it would to dig up the streets of Port-au-Prince to lay underground sewage lines. And the output is used as agricultural compost. [41]

Small-scale initiatives at the household level are also being introduced. For example, the non-profit company Sanergy provides sanitation to urban slums in Kenya by pairing a franchise model with a low-cost, high-quality toilet that takes up very little space. The waste is collected daily and converted to organic material or used to generate renewable energy. Local operators purchase and operate the facility, ensuring that it stays clean and accessible.

A for-profit social enterprise in India has approached the challenge of water provision in a similar way. The cost of piping water to every household is expensive, time-consuming and sometimes impossible. Savajal provides solar-powered water ‘ATMs’, which sell safe drinking water to those without access to a citywide system. Initially installed in rural areas, these are now being introduced to the city of Delhi. The dispensers accept smartcards similar to prepaid phone cards and can be accessed 24 hours a day.

Box 5. Rio’s central command office |

|

In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a central operational command office — the world’s most ambitious — using communications and wireless technologies opened in late 2010 through a partnership with IBM. [42] This office acts as clearinghouse of information from 30 governmental agencies throughout the city. It allows information to flow in from the streets so that quick and coordinated responses to emergencies — as well as to ongoing activities such as traffic or waste collection — can be provided.    The system’s monitoring capabilities activate automatically during extreme events such as floods, warning citizens in vulnerable locations. Information technology makes such a system possible — but at the hefty price tag of US$14 million. And it doesn’t necessarily solve underlying challenges such as inefficient infrastructure. [37]. The system’s overall impact is still unclear. [43] Claims that emergency response times are down by 30 per cent contrast with local people’s accounts as well as with statistics showing a recent surge in crime. [44,45,46] |

Where to go from here?

Better planning, integrated design and instrumental technologies are transforming cities. But scaling up the innovative cases shared above is still a challenge. And ‘one-size’ won’t necessarily fit all, while solutions that work in the developed world do not necessarily work in the developing world. So knowledge needs to be shared in both directions. Basing urban sustainability efforts on local realities tends to give the best results. For example, learning from migrant communities in informal settlements is one way to reimagine urban planning.

Networks and communities of practice are ensuring that lessons learned are being shared globally — the Rockefeller Foundation has recently launched the 100 Resilient Cities Challenge and the World Bank, with other partners, is funding the Low-Carbon Livable Cities Initiative to share methods and tools. The ultimate goal is to transform cities to green, well-planned, inclusive, resilient, productive, safe, and healthy places to live.

Kate Hawley is an economics research associate at ISET International in Colorado, USA. She can be contacted at [email protected] and on Twitter @KateISET

| Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) | A high-capacity public transport system that combines elements such as stations, ‘clean’ vehicles and advanced digital technologies into an integrated system. It uses buses or specialised vehicles to quickly and efficiently get passengers to their destinations. It can easily be customised to particular communities’ needs and can incorporate technologies, such as traffic management, that result in more passengers and less congestion. |

| Closed-looped systems | Systems where all waste is recycled and reused. For example, cities are starting to adopt decentralised wastewater treatment facilities that capture the heat released from sewage, which can be used to heat homes. The organic waste is turned into biofuels or fertiliser. |

| Eco-cities | Cities built on the principle of living within environmental limits. Many eco-cities aim to eliminate all carbon emissions, produce energy entirely from renewable sources and generally to incorporate ‘green’ principles into city design. Cities with slightly less stringent aims may be described as ‘green’ cities. See also low-carbon cities and zero-energy cities. |

| ‘Green’ cities | Cities that have made becoming more environmentally responsible a priority. They may use management techniques to reduce their environmental impact, calculate their ‘ecological footprints’ (a measure of the amount of resources they use) or meet goals around energy efficiency and renewable energy. Cities with similar characteristics may be described as eco-cities. |

| Informal settlements or slums | Groups of housing units constructed on land to which the residents have no legal claim. |

| Integrative design | Design that takes into account the urban system as a whole. It is usually an iterative process that aims to involve all stakeholders, breaking down traditional linear approaches where the design is handed down from owner to architect, builder and occupant. Such an approach allows flexibility to reach different solutions in each new environment where it is applied. |

| Low-carbon cities | Cities focused on reducing their carbon footprint and keeping emissions as low as possible. See also eco-cities and zero-energy cities. |

| Peri-urban | The area immediately surrounding a city, between urban and rural areas. |

| Resilient cities | Cities designed to systematically respond to and cope with human, natural and other stresses. Their aim is to withstand shocks such as natural disasters, absorb them and even grow after such events. |

| ‘Smart’ cities | Cities that have integrated technology and information systems into their operations to manage resources more efficiently, improve monitoring and facilitate decision-making. The vision of a smart city is that of ‘networked urbanism’, in which all systems feed into a central control mechanism on a day-to-day basis. |

| Sustainable development | Defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. |

| Urban | There is no single definition of what makes an area urban. It can be defined by one or more of the following elements: a minimum number of people living in an area; the population density in an area; the number of people employed in different sectors, particularly non-agricultural sectors; and the existence of basic services such as roads, electricity and healthcare. Just a quarter of countries use population size and density to define an urban settlement, and many also consider administrative criteria such as boundaries defined and managed by different governmental entities. |

| Urban form | Urban form can be unplanned (natural) or planned development of a city. Many characteristics make up urban form, such as the landscape (topography, location, soils, and so on), the buildings and how the built environment relates to outdoor space (such as parks and green areas). |

| Urban growth | The increase, in absolute terms, in the number of people who live in towns and cities. It comes from natural population growth in urban areas but also rural-urban migration; sometimes it also reflects administrative changes in the designation of land from rural to urban. The rate of urban growth is the increase in urban population over time or the pace of urban population growth. |

| Urbanisation | The increase in the proportion of people living in cities and towns relative to rural areas. The rate of urbanisation is the increase in the proportion of population that is urban over time, calculated as urban growth rate minus total population growth rate. |

| Urban poverty | Globally, absolute poverty is defined as having an income below US$1 a day — but urban poverty is much more challenging to determine and define. Many elements contribute to urban poverty that are not often incurred in rural settings, such as the cost of goods and transport. So some argue that urban poverty may be more appropriately measured as relative poverty (defined by standards that differ depending on the setting). |

| (Net) Zero-energy cities | Cities focused on producing the energy they need in a given year, resulting in net-zero energy use. Zero-energy cities have three main characteristics: incorporating maximum energy efficiency into the design of the entire city, generating energy on-site, and purchasing renewable energy produced off-site to meet any remaining energy needs. See also low-carbon cities. |

This article is part of the Spotlight on Transforming cites for sustainability

References

[1] United Nations World Urbanization Prospects: the 2014 revision, highlights (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014)

[2] André Sorensen Towards Sustainable Cities (Ashgate Publishing, 2014)

[3] Eva Charvekwieiz Transitions to sustainable production and consumption: concepts, policies, and actions (Shaker Publishing, Maastricht, 2001).

[4] IUCN and others. World conservation strategy: living resource conservation for sustainable development , (IUCN, UNEP, and WWF 1980)

[5] David Satterthwaite Sustainable cities and cities that contribute to sustainable development? (Urban Studies, 1997)

[6] Herbert Girardet Cities people planet: liveable cities for a sustainable world (John Wiley & Sons Ltd UK, 2004)

[7] Jorge Hardoy and others Environmental problems in an urbanizing world (Earthscan Publications, 2001)

[8] United Nations The state of the world’s children 2012: children in an urban world (UN Children’s Fund, 2012)

[9] Timothy Elkin and others Reviving the city: towards sustainable urban development (Friends of the Earth, 1991)

[10] Elizabeth Williams and others (eds) A compact city: a sustainable urban form? (E & FN Spon, 2004)

[11] P. Anastasiadis and G. Metaxas Sustainable city and risk management (1st WIETE Annual Conference on Engineering and Technology Education. Pattaya, Thailand, 2010)

[12] McKinsey Global Institute Urban world: mapping the economic power of cities (2011)

[13] United Nations World economic and social survey 2013: sustainable development challenges (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013)

[14] Barney Cohen Urbanization in developing countries: current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability (Technology in Society, 2006)

[15] Diana Mitlin and David Satterthwaite Urban poverty in the global south: scale and nature (Routledge, 2013)

[16] Lawrence Haddad Poverty is urbanizing and needs different thinking on development (The Guardian, 5 October 2012)

[17] Global energy assessment: toward a sustainable future (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria, 2012)

[18] Marc Cohen and James Garrett The food price crisis and urban food (in)security (Environment and Urbanization, 2010)

[19] WHO and UNEP Healthy transport in developing cities (WHO and UN Environment Programme, 2009)

[20] WHO Road traffic fact sheet (WHO, 2013)

[21] Lance Saker and others Globalization and infectious diseases: a review of linkages (UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank, & WHO, 2004)

[22] World Bank Urban solid waste management

[23] Neil Armitage The challenges of sustainable urban drainage in developing countries (SWITCH Conference, Paris 2011)

[24] Aromar Revi and others Urban areas (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group II, contribution to the 5th Assessment Report, 2014)

[25] Jeb Brugmann Financing the resilient city (Environment and Urbanization, 2012)

[26] The World Bank Cities and climate change: an urgent agenda (World Bank, 2010)

[27] United Nations Revealing risk, redefining development: the 2011 global assessment report on disaster risk reduction (United Nations, 2011)

[28] IFRC World disasters report: focus on urban risk (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2010)

[29] United Nations Housing for all: the challenges of affordability, accessibility and sustainability (UN Human Settlements Programme, 2008)

[30] Peter Naess Urban planning and sustainable development (European Planning Studies, 2001)

[31] The sustainable city (Diamond Developers)

[32] The Masdar ‘Green’ city (CH2M HILL)

[33] Susan Anyangu-Amu Kenya: mapping an Africa slum (Inter Press Service News Agency, 2010)

[34] Paul Hawken and others Natural Capitalism (Little Brown and Company, New York USA, 1999)

[35] Kizito Makoye Green machine: Dar es Salaam backs low-carbon buses to beat traffic jams (The Guardian, 27 March 2014)

[36] Sarah Munir Transport Planning: case study Bogota, Columbia (Published on Scribd, 2012)

[37] Busby Perkins+Will and Stantec Consulting Roadmap for the integrated design process (2007)

[38] ISET-International A concept of resilient housing: Da Nang, Vietnam (Boulder, Colorado USA, 2014)

[39] Janine Benyus Biomimcry (William Morrow and Company, Inc, New York USA, 1997)

[40] Abigail Doan Biomimetic architecture: green building in Zimbabwe modeled after termite mounds (Inhabitat, 2012).

[41] Richard Knox Port-Au-Prince: a city of millions, with no sewer system (NPR, 13 April 2012)

[42] Natasha Singer Mission control, built for cities (The New York Times, 3 March 2012)

[43] ARUP Innovators: international case studies on smart cities (Report produced for the UK Department for Business Innovation and Skills, October 2013)

[44] Jesse Berst Why Rio's citywide control center has become world famous (Smart Cities Council, September 2013)

[45] Christopher Frey World Cup 2014: inside Rio’s Bond-villain mission control (The Guardian, 23 May 2014)

[46] Clarissa Thomé Violência no Rio de Janeiro retoma níveis pré-UPPs (Estado, 3 May 2014)