By: Shahani Singh

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

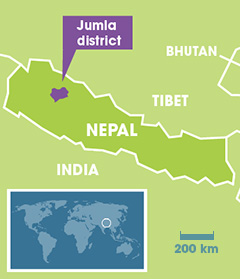

When the indigenous Jumli Marsi variety of rice, grown in Nepal’s Jumla district, was hit by blast infection, farmers were forced to replace it with the Chandannath 1 and 3 hybrids that originate in China.

These hybrids stood up well against the rice blast fungus, so farmers were happy. But only for a while. Farmers and consumers soon realised that the hybrids made for a less satisfying meal than Jumli Marsi.

“We took a perception survey and found that people prefer to eat Marsi. There is some truth to it — perhaps the nutrition value is high in Marsi,” says Bal Krishna Joshi, senior scientist and plant breeder at the National Agriculture Genetic Resources Center (Genebank) in Kathmandu. “Marsi soaks up milk and ghee and becomes sweet,” he adds.

Scientists at the ‘Integrating Traditional Crop Genetic Diversity for Mountain Food Security Project’ are currently developing a varietal blend of Jumli Marsi and Chandannath 1.

But there are difficulties. “At the policy level, there are no provisions for mixing,” says Joshi. “We have yet to debate whether, in order to register a varietal blend, we ought to register the blend, the parent varieties or register the technology. We need to create a provision for it.”

Nepal’s experts are calling for a new approach to protect local seeds. And farmers such as Bishnu Bahadur Rawal are looking for assurance on their basic rights and an evidence-based agriculture policy to harness local knowledge.

“We heard about an agriculture policy three years ago over the radio, but we have not seen anything on the ground yet,” Rawal says. “If a proactive farmer like me has not seen the policy, then farmers in remote and far-flung areas are unlikely to have even heard of it.”

Rawal raised the issue at a training workshop held at Genebank last December that aimed to strengthen the seed system of local crops. “It would be better if the policy is revised and reformed after considering inputs from farmers. Farmers do not know much about the policy — or even that there is one,” he said at the workshop attended by farmers, researchers, seed companies and a top government representative.

Joshi, who was also at the workshop, said that the existing system does not openly support the marketing of indigenous seeds that increase biodiversity and boost the local economy.

“The government has to prioritise conservation of neglected and underutilised crops in terms of research, investment and preparation of an institutional framework that covers human resources and educational materials,” Devendra Gauchan, agriculture economist and project manager at the Nepal office of research organisation Bioversity International, tells SciDev.Net.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s South Asia desk.