By: Bruno Awio and Inga Vesper

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The second of our INASP/SciDev.Net data challenges features an agricultural project from Uganda. A team of scientists joined 358 farmers in two districts to test the best bean they were growing in terms of robustness, yield and marketability. And most importantly, a bean that can prosper in the dramatically changing climate affecting the whole of East Africa.

Around 23 million tonnes of beans are grown globally for trade and local consumption every year. Across the world, millions of farmers depend on one or more of the 40,000 known bean varieties.

But beans are a fragile crop. They need lots of water and stable temperatures to grow. A research paper out this month shows that up to 60 per cent of areas in Sub-Saharan Africa in which beans are currently grown may become unsuitable for such crops by 2100, because of rainfall and temperature changes.

For Bruno Awio, a plant breeding researcher in Uganda, this problem raised important research questions.

Which beans grow best under which conditions?

To find out, he chose two districts as breeding grounds: Hoima and Rakai. They are nearly identical in terms of population, economies and their environment, but with one crucial difference: rainfall.

Hoima district is in the western hills of Uganda, bordering on the Democratic Republic of Congo. More than half a million people live here, most of whom rely on subsistence farming. Hoima has seen rising rainfall over the past decade.

Rakai district is in the south and borders Tanzania. Like Hoima, most people here farm for a living. But Rakai is getting drier.

“Our motivation was to find districts experiencing contrasting climatic situations, so we would be able to transfer their experiences to other parts of the country,” says Awio, who did the research as part of his PhD at Uganda’s Makerere University.

Farmers' study

In 2012, Awio teamed up with CGIAR, a global agriculture research partnership, to study how different bean varieties perform in different climatic conditions.

-

The bean trial in 2012

-

Trials were set up in five villages in Hoima and four in Rakai

-

A group of 143 male and 215 female farmers signed up to the trial

-

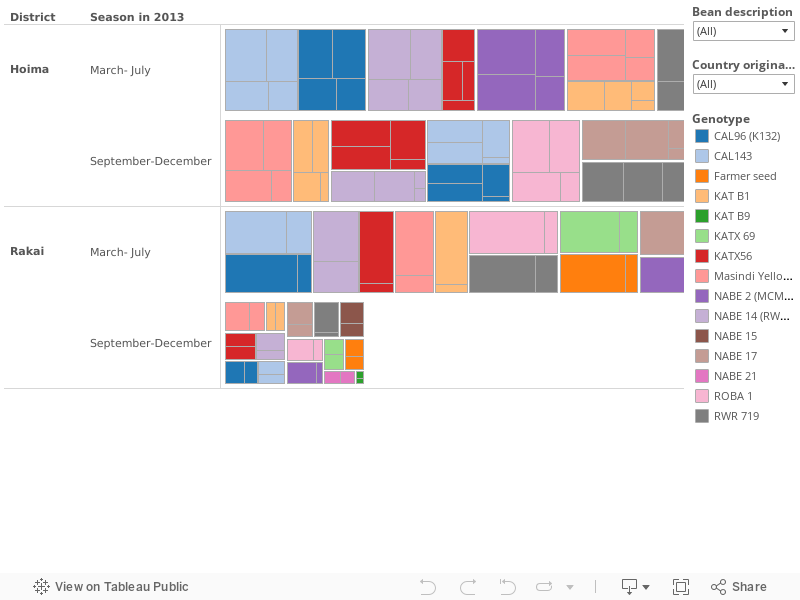

The farmers tracked the growth and harvests of 15 bean types over two growing seasons in 2013

-

They reported additional data on fertiliser use, weather conditions and bean sales

-

Farmers were also asked to mark the desirability of the beans

-

This was compared to scientific findings to rate the beans overall

Farmers were asked to report on bean performance and to select their favourite bean based on how well it sold, which would then be compared with the scientific findings.

Fifteen beans from four African countries were tested in the Ugandan regions of Hoima and Rakai. Project leader Bruno Awio’s data shows each bean’s performance during two growing seasons in 2013.

The best bean: Masindi yellow

“Farmers showed a preference for the Masindi,” Awio says. This was especially true for female farmers, he says, as, not only was there a market for the bean, but it was also highly palatable for family meals.

Awio’s research showed that male and female farmers look for different kinds of beans. Men were primarily interested in the market value of beans and the yield. Women also needed a good sales value and high yields, but they wanted additional benefits, such as short cooking times, tastiness and high nutritional value.

Masindi provided high yields of tasty beans in all environments studied. Regional varieties, especially the NABE type of bean endemic to Uganda, also performed well, and was especially popular with male farmers.

“The regional types are small-seeded, but they produce a lot of pods,” Awio explains. “Plus they are resistant to a number of diseases predominant in the area”, reducing the need for costly pesticides.

At the pulse of bean farming |

Godfrey Kairagura, 50, farmer in Kyabigambire, Hoima districtBefore this project, we did not have the knowledge about the best crops for farming. It trained us how to plant beans better, and how to plant different selections. Before, we also had problems using fertiliser — the scientists advised us on the best to use. Another challenge was how to market our beans and we were mobilised to work together and share our experience of the market. I participated because I wanted to improve my farming skills and get access to technical knowledge. But because I was suddenly working with other farmers in the region, the project encouraged us to share ideas as a group rather than just working as individuals. I was exposed to other experiences because of participating in this group. We used to just plant the mix of bean varieties that were available, but now we have the technology to select the beans to suit the weather. I also now have rain gauges to help identify climate change. The rain gauges tell us when the rainy season can be expected. This is important, because my farm is affected by climate change. Right now, the seasons have changed completely. We used to have two rain seasons, but now we have rain all the time — the pattern is changing completely. There is no fixed timetable any more. At the moment it is dry, but in January it was raining a lot. We planted the beans, but by February the rain had gone. We are badly affected because, in a case like that, we use all the seeds and then we don’t have any left. We are losing a lot of seeds and crops because the rain seasons are not reliable any more. |

The success of the project means that farmers in the region now have the technical information to decide which crops to grow, rather than relying on chance, price and market availability. They will continue to monitor the changing weather to update their practices. As further research, Awio says it is now important to work in the lab with the top-performing beans to make them even more robust to withstand changing conditions, ensuring sustainable crops for the farmers.

Bruno Awio is the winner of a data challenge offered to INASP-supported researchers to encourage collaboration between journalists and academics to produce data-driven stories.