By: Elizabeth Smout

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Ebola’s challenges hold lessons for other health emergencies. Elizabeth Smout examines what worked, and what didn’t.

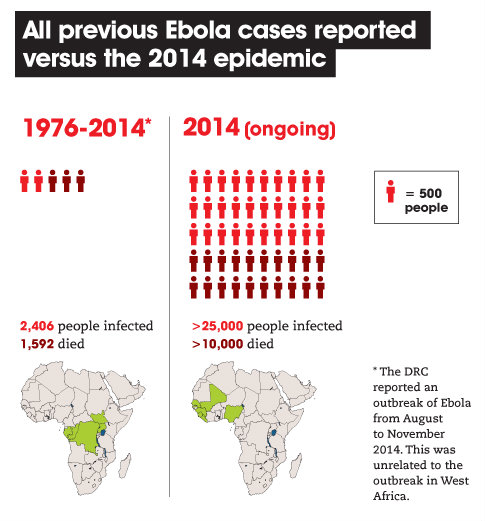

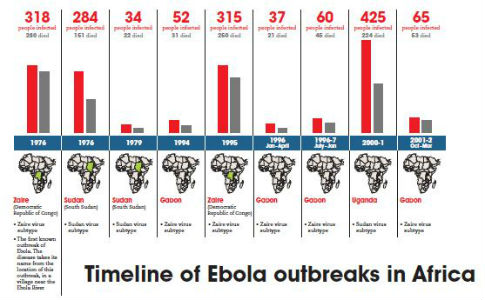

The ongoing Ebola outbreak in West Africa has devastated Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. It is the largest epidemic of the disease ever recorded (see Figures 1 and 2). The economic impact is huge, accounting for as much as US$25.2 billion in lost GDP (gross domestic product) in 2014-15, according to the World Bank. [1] The number of deaths is an obvious measure of the human cost, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. The virus is transmitted through behaviours that represent the best of human nature — caring for the sick, showing reverence for the dead, showing affection — and this epidemic has torn through the social fabric of entire communities.

The isolation and treatment of people infected, or suspected of being infected, with the Ebola virus has been at the forefront of efforts to tackle this epidemic of a serious and unfamiliar disease (see Box 1). Though medically and scientifically appropriate, this strategy has had to grapple with social, cultural and political dynamics. A critical look at the complications and experiences from the perspective of communications and social science holds lessons for future public health responses to infectious disease outbreaks.

Box 1. Ebola facts and timeline

- The disease

- Ebola is a viral haemorrhagic fever caused by filoviruses. There are five known species of Ebola virus.

- Infection from animals

- People can become infected after close contact with infected animals such as fruit bats, apes and monkeys.

- Human transmission

- The disease can spread from person to person through direct contact with infected blood and bodily fluids or those who have recently died of the infection.

- Myths

- There is no evidence that Ebola can spread through the air, water, food or mosquitos.

- Becoming infectious

- Signs of Ebola may appear as early as two days after exposure or as late as 21 days.

- Symptoms

- Symptoms include fever, headache, joint and muscle pain, sore throat and muscle weakness. As the disease progresses the patient develops diarrhoea, vomiting, a rash, stomach pain and damage to the kidney and liver. In advanced stages, there is internal bleeding as well as bleeding from the nose, eyes, ears and mouth.

-

Fatalities

- At least 50% of those infected die of Ebola. There is no cure or licensed vaccine.

Historical vulnerabilities

Understanding how the Ebola epidemic took hold in West Africa requires some knowledge of the region’s history. Decades of civil war have destroyed healthcare systems and general infrastructure across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. People generally depend on non-evidence-based ‘alternative’ treatments for disease. Self-medication or using traditional healers is common across the region because patients cannot rely on government-run facilities having enough staff, stocks or equipment. During the epidemic, people often turned to informal healthcare providers for another reason: widespread beliefs that hospitals and healthcare facilities — particularly those run by international organisations — were the source of Ebola infection.

In the first section of a two-part interview, Melissa Leach, director of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom, talks to Imogen Mathers about local people’s distrust of state and international health services during the Ebola crisis. She discusses the intersecting social and historic reasons why people in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone might be suspicious of emergency health workers sent by their government and global NGOs.

The legacies of both colonial rule and post-colonial conflict have affected communication between local people and those responding to the crisis. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone have experienced years of oppression and inequality, and international and national exploitation of the region’s riches. This has led many citizens to be suspicious of government motives and to dismiss public health messages in favour of their own interpretations of the Ebola outbreak’s origins. [5] The resulting distrust complicated delivery of official public health messages. [6]

Rumours and misinformation around Ebola became heavily politicised in Sierra Leone, for example. When the first cases emerged in Kailahun, a district in the heartland of the main opposition party, they prompted rumours that the country’s ruling party had set up ‘death squads’ to take whole communities to treatment centres in order to administer a lethal injection and reduce the opposition’s support. Similarly, in Liberia, people accused President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of deliberately poisoning citizens and of exaggerating the scale of the epidemic in order to receive international donor money. [7]

Poor infrastructure also undermines communication: even the most seemingly appropriate communications strategy cannot succeed if there are no roads or transport networks to move patients to a clinic for treatment, or if a weak telecommunications network means public health messages do not reach across the country. By contrast, population movement is fluid in West Africa. Population mobility here has been estimated at seven times higher than in the rest of the world. [8] The constant flow includes traders, families and people seeking health care closer to their ancestral homes. Movement across borders and within countries is virtually impossible to control; this brings more people within reach of the virus and takes the virus to new populations.

If misunderstood, issues such as these can also influence the international community’s perception. During this outbreak, local attitudes towards Ebola have often been generalised to an entire district or country, or stereotyped as relating to beliefs around witchcraft or traditional healing — which are seen as obstacles to achieving medical control of the outbreak. [9]

These experiences show clearly that communication cuts across many issues beyond the scientific validity of public health measures, with real impacts on emergency responses. Without an effective communication strategy to mobilise or marshal communities, local people may not seek treatment when an infection is suspected. Without effective communication between organisations working on the ground, resources will not be directed to where they are most needed. And unless governments share information, cross-border management of an outbreak will suffer.

Communication is a vital ingredient

For epidemic control to be successful, interventions must amount to an adequate solution. If they are too few, or not timely, or are inappropriate, the response will fail. A briefing paper by the medical aid charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) — which was first on the scene in West Africa and at the forefront of efforts to tackle the epidemic — describes the response to Ebola as “falling dangerously short”, with inadequate staffing and a severe shortage of facilities, particularly in rural areas. [10]

Experience with this and other health emergencies also shows that communication is often a crucial influence on whether or not a particular intervention will work. A study conducted in the United Kingdom during the flu pandemic of 2009 found that the uptake of protective behaviours against the virus, such as buying hand sanitisers, was clearly correlated with increased media coverage and advertising related to swine flu. [11] In the United States, a poll by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, conducted within ten days of the first swine flu report in the country, found that most US citizens were aware of the basic facts around the disease and how to prevent it. This was largely credited to open and frank communications about the epidemic. [12] A wealth of evidence has also shown the fundamental role that communication has played in tackling HIV/AIDS — it influences knowledge, attitudes, risky behaviours and decisions to seek care and adhere to treatment. [13]

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, a senior member of the MSF response team in Guinea said that the charity’s heavy focus on the need for more treatment beds came at the expense of paying enough attention to delivering public health messages and education for communities. [14] The result was resistance towards Ebola response teams (see Box 2). This reflection, by the organisation that has arguably been the greatest contributor to the response, puts the role of communications during health crises into the spotlight once again.

Box 2. Resistance to Ebola responses in West Africa |

| Guinea has seen much resistance to official efforts to tell people about Ebola and to trace contacts of infected individuals. In September 2014, eight local officials, healthcare workers and journalists attempting to raise awareness of the disease were killed by a group of angry residents in the village of Womey. [15] A recent report details how Red Cross teams have faced an average of ten attacks a month in Guinea since the Ebola outbreak began, including teams conducting safe burials being stoned. [16] West Point, the largest slum area of Monrovia, Liberia, has also shown intense resistance. An attack on a quarantine centre in August 2014 led to infectious patients, medical equipment and mattresses being removed from the facility. The government put the slum into lockdown. Violence followed as residents protested at a lack of food and because bodies were not being collected. A 15-year-old boy was shot dead by the police during this episode. [17] |

Building relationships

In general, organisations involved in responding to Ebola did not prioritise building relationships with affected communities from the outset. They did not develop a detailed understanding of people’s perceptions and experiences, and this led to resentment. Information sharing works best as a dialogue facilitated by trained local people acting as social mobilisers — because people known to the community are more able to engage others in conversation and be trusted with their concerns.

It’s also important to have dialogue between countries, and between local and national governments. Concerns over resources to tackle the epidemic or local patterns of Ebola’s spread need to be discussed with the national government; and, conversely, guidelines and developments on issues such as hazard pay (compensation for work under dangerous conditions) or quarantine measures need to filter down to the local level.

At the national level, coordination helps to align communication and containment strategies — the flow of people across borders in the region makes this crucial. In January, MSF raised concerns about the lack of information sharing between countries. [18] There are now signs of improvement. A memorandum of understanding has been signed between Kambia district, Sierra Leone, and neighbouring Forecariah prefecture, Guinea; it outlines an agreement for shared discussions, community awareness efforts and resources to tackle the epidemic. As with high-level talks, practical strategies can be aligned through discussions between neighbouring district response teams across borders.

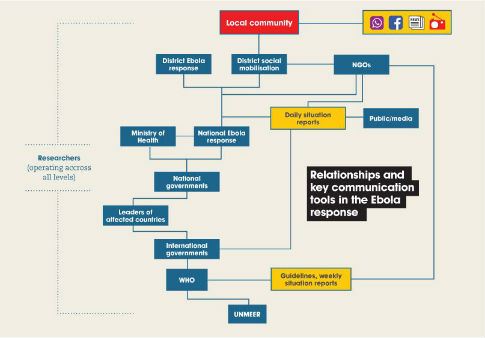

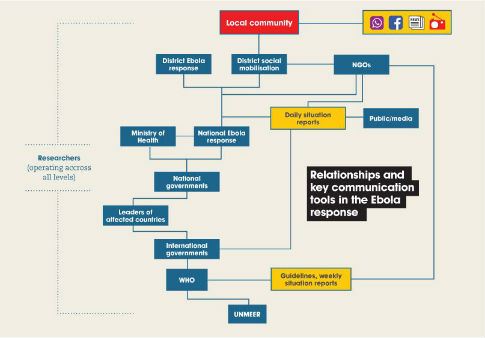

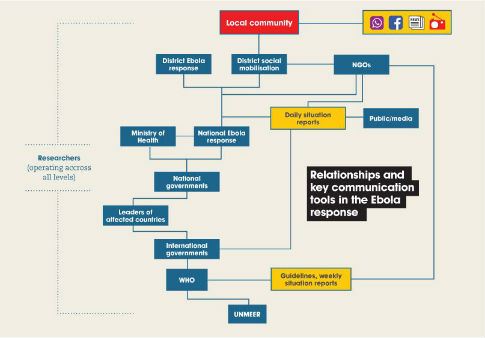

All the numerous partners involved in the response (See figure 3) need effective communication. Their sheer number and their different mandates makes coordinating communications activities extremely complex. This is typical of health crises: mounting an emergency response generally requires a wealth of expertise in a variety of fields, from medical care to data management to logistics. But the scale of the West African challenge has been unprecedented. With so few existing structures in place in affected countries, the response has had to virtually start from scratch. It has been a case of everyone getting to the front line.

The intense global interest in this outbreak has also translated into a much greater demand for information than most health crises (see Box 3 for a summary of sources). At present, materials produced to help NGOs and other organisations inform communities about Ebola have to be approved by the relevant ministry in each country and partners with technical or scientific expertise such as UNICEF (the UN Children’s Fund). This minimises the risk of spreading false information and rumours.

| Box 3. Sources of Ebola updates | |

|---|---|

| World Health Organization (WHO) provides weekly situation reports, whose figures are frequently quoted in the media | |

| UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER) produces situation reports, guidance, meeting notes and other resources | |

| MSF issues crisis updates, interactive guides and blogs from the field | |

| Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Health and Sanitation provides daily situation reports and Liberia’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare provides daily situation reports. These reports are based on epidemiological investigations supported by the WHO, but some have tended to be out of date by the time they are uploaded, particularly in the earlier stages of the epidemic. |

Communication tools

Various communication tools, both traditional and innovative, have been used to fight Ebola. Newspapers, radio and television have all been broadcasting almost constant Ebola-related messages and discussions both locally and nationally in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Rachel Aveyard is project manager for Mr Plan-Plan, a BBC Media Action drama series broadcast in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone to help people understand how to protect themselves against Ebola. In this audio interview she talks to Imogen Mathers about producing Mr Plan-Plan and why drama and radio are such important vehicles for making public health information accessible and applicable to people’s everyday lives. She also outlines a few of the logistical barriers to delivering the show to hundreds of partner stations across countries where internet and transport networks are poor or non-existent. And she explains why it is that radio dramas carry a value that extending far beyond the broadcasts themselves.

Radio is particularly important in the region and in much of the developing world. A study in 2011 estimated that 86 per cent of women listened to the radio in Sierra Leone, 81 per cent in Liberia and 74 per cent in Guinea. [19] Radio programmes in the region have incorporated short public service announcements about Ebola, panel discussion programmes where the public can call or text their questions into the show, and longer radio dramas. BBC Media Action, for example, has developed a radio drama, Mr Plan-Plan and the Pepo-oh, which has been broadcast repeatedly in each affected country.

The programme was developed to counter the overwhelming ‘what not to do’ messages during the outbreak with a focus on what people could do to prepare, to stop the virus spreading and to respond if someone around them did get infected. [20]

Instant messaging services such as WhatsApp have also been enormously important tools for informal information sharing, with both helpful and damaging effects. People use them to take part in large group discussions where information from official briefings, press releases and news articles is shared, together with rumours and group members’ concerns. While this lets up-to-date information reach many people almost instantly, the risk of spreading misinformation is extremely high. The conversations are not moderated, and hoax messages are rife.

The outbreak has also led to innovation. Organisations such as UNICEF and IBM have developed systems where people can call or text to report concerns about the response, and provide real-time information to the ministry of health and district response centres on where resources need to be directed. [21] Several Ebola songs have been written: to spread messages, as tributes to victims or as political statements. For example, a song entitled White Ebola expresses the widespread distrust and denial at the beginning of the epidemic. [22] The Global Alliance to Immunise Against AIDS (GAIA) developed a story-telling cloth pattern designed to be worn by health workers talking with communities. [23]

Information given, information needed

The information given by various agencies does not always match the information needed by the people affected.

Research conducted in Liberia found that, while community leaders believed they understood basic messages on the virus and its transmission, they also said they had not been given advice on how to actually manage patients in their communities. [20] Anecdotal evidence also suggests that, as information flows down to the community, unofficial reports by the general public overshadow scientific information. This does not necessarily mean that people ignore educational material about the virus, but rather that the public is often more concerned with how the outbreak may affect their daily lives. For example, information spreading through informal networks in Sierra Leone has gradually shifted focus from denying that Ebola is real and questioning the science, to rumours surrounding lockdowns and their impact on the general public.

In the early stages of the outbreak, agencies with technical expertise such as the WHO strongly emphasised not eating bushmeat as a control strategy. Although research has linked bushmeat with the spread of Ebola from animals to humans, the risk appears limited to people who hunt and prepare raw meat, and once an outbreak takes hold, interaction with people is what drives an epidemic. [24] But this nuance in scientific knowledge was initially lost, with harmful consequences. The early messages risked leading communities to believe that avoiding bushmeat is more important than not touching dead bodies. [25]

Response starting with local people

Giving messages and instructions without offering information or training that lets communities develop their own response has been a recurring difficulty in disease outbreaks. [27] Too often, public health messages have been delivered with little appreciation of community context, and social and cultural beliefs have been dismissed as being barriers to effective disease containment. In this outbreak, insight from social science has helped to facilitate dialogue, develop an understanding of social context and adapt practices so they become culturally sensitive.

In the second section of a two-part interview, Melissa Leach, director of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom, talks to Imogen Mathers about the reasons behind resistance to some of the control measures initially imposed on people when Ebola broke out in West Africa. She explains why the global emergency response needs to engage more robustly with local people early on during disease outbreaks — in this crisis, it was important to identify and better understand beliefs and practices relating to healthcare, death and funeral rites.

The importance of community-level initiatives in the Ebola response cannot be overstated, particularly in rural areas where traditional leadership structures dominate (see Box 4). Chiefs, religious leaders, traditional healers and other civil society leaders are all hugely influential, and their involvement and support can make or break local Ebola response efforts. If people’s concerns are going to be understood and addressed by communications efforts, local ‘buy-in’ is essential.

One could argue that failing to listen to local concerns characterises public health responses everywhere, not just in poorly resourced countries. For example, after the outbreak of measles that began in Disneyland in the US state of California in December 2014, there was immediate and widespread condemnation of the anti-vaccination movement. But some parents who had been against the vaccine have reversed their decision and taken their children for vaccination after having an opportunity to openly discuss the reasons behind their hesitancy with their doctor, rather than having their fears instantly dismissed as irresponsible. [28] Some would also argue that distrust and fear, fuelled by a long-standing history of negative publicity about the combined MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine, contributed towards the initial fears of parents — only for those fears to be overshadowed by the imminent threat of a developing epidemic.

Box 4. Examples of community mobilisation against Ebola in West Africa |

|

Communities themselves understand what they need to effectively respond to disease outbreaks. A prime example of this was seen during an earlier outbreak of Ebola in Uganda. To begin with, people thought they had a common illness and sought both medical and traditional treatments. But they soon recognised that it was more serious, and began referring to their illness as the workings of a very bad spirit. By simply communicating among themselves about the outbreak in these terms, self-quarantine was applied to affected households for fear of the evil spirit affecting anybody else, and the outbreak was successfully contained. [29]

During the current outbreak, social anthropologists invited community and opinion leaders from ‘resisting’ villages in Guinea to a workshop with organisations involved in the response. The aim was to ensure that people were heard, and to develop a shared strategy for engagement and education based on their needs and concerns. [5] As a result, community leaders publicly committed to ensuring that their communities were trained in basic hygiene practices and pledged to ease their resistance towards contact-tracing teams. In return, response organisations agreed to provide resources to decentralise the management of the epidemic and ensure the response better reflected local needs. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) has advocated for local people to lead the development of prevention strategies within their area, rather than simply delivering messages developed by other organisations, usually without local involvement. [30] The IRC has also promoted local ‘ownership’ of response efforts by developing an early warning system in which nominated community health workers act as monitors, reporting on any worrying events in the community via a mobile phone. Any report then triggers a visit from a surveillance worker to investigate. [31] The Social Mobilisation Action Consortium (SMAC) in Sierra Leone has brought together a group of five organisations involved in the Ebola response — BBC Media Action, Focus 1000, GOAL, Restless Development and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — to lead the largest community mobilisation effort ever held in the country. [32] The focus of their approach is to encourage community-led action through training and by empowering communities to act and take responsibility for tackling the outbreak within their own area. |

Listening and learning

There is no doubt that crisis management systems, and particularly communications during crises, can and should be reviewed in light of this unprecedented outbreak. Communicating effectively has been hugely complicated, but, as the epidemic wanes, there is an opportunity to review practices and learn lessons.

At this stage, there are no definite dos and don’ts, but there are success stories to draw on, including the people-led responses, innovations and institutional initiatives highlighted above. With so many partners involved, it is also important that communications are coordinated from a single reference point, preferably as part of the district-level response. They would be responsible for knowing who has information, who needs it and how best to share it, and this would help to ensure that people are aware of who is involved in information sharing and how.

The outbreak has also shown the value of communications strategies that start by listening to local concerns and continue through constant dialogue. Such initiatives need to be linked with district and national coordination systems, so that people’s needs are represented at high-level discussions. This is particularly important in a situation where suspicion, stigma and misinformation are rife. Only through open information sharing and dialogue at all levels can challenges be overcome, trust gained and epidemics as devastating as Ebola be stopped.

Elizabeth Smout is a researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, and is currently based in Sierra Leone. She works as part of The Vaccine Confidence Project, which examines social and political determinants of public trust in health programmes. She can be contacted at [email protected]

This article is part of our Spotlight, Managing health crises after Ebola.

References

[1] The economic impact of the 2014 Ebola epidemic: short and medium term estimates for West Africa (World Bank, October 2014)

[2] Transmission | Ebola haemorrhagic fever (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, updated 9 April 2015)

[3] Outbreaks chronology: Ebola virus disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, updated 20 April 2015)

[4] Ebola situation report (WHO, 25 March 2015)

[5] Julienne N. Anoko Communication with rebellious communities during an outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea: an anthropological approach (ebola-anthropology.net, accessed 12 April 2015)

[6] Ashoka Mukpo The biggest concern of the Ebola outbreak is political, not medical (Aljazeera America, 12 August 2014)

[7] Helen Epstein Ebola in Liberia: an epidemic of rumors (The New York Review of Books, 18 December 2014)

[8] Atlas on Regional Integration in West Africa Population series: migration (ECOWAS-SWAC/OECD, August 2006)

[9] Jared Jones Ebola, emerging: the limitations of culturalist discourses in epidemiology (The Journal of Global Health, accessed 12 April 2015)

[10] Ebola response: where are we now? (Médecins Sans Frontières, December 2014)

[11] G. J. Rubin and others The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK (Health Technology Assessment, July 2010)

[12] Brendan Maher Swine flu: crisis communicator (Nature, 13 January 2010)

[13] Douglas Storey and others What is health communication and how does it affect the HIV/AIDS continuum of care? A brief primer and case study from New York City (Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, August 2014)

[14] Misha Hussain MSF says lack of public health messages on Ebola ‘big mistake’ (Reuters, 4 February 2015)

[15] Amy Brittain The fear of Ebola led to slayings — and a whole village was punished (The Washington Post, 28 February 2015)

[16] Ebola crisis: Red Cross says Guinea aid workers face attacks (BBC News, 12 February 2015)

[17] Joe Shute Ebola: inside Liberia's West Point slum (The Telegraph, 16 December 2014)

[18] An encouraging decline in Ebola cases, but critical gaps remain (Médecins Sans Frontières, 26 January 2015)

[19] Frances Fortune and others Community radio, gender and ICTs in West Africa: how women are engaging with community radio through mobile phone technologies (Search for Common Ground, July 2011)

[20] Sharon A. Abramowitz and others Community-centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: the view from below (ebola-anthropology.net, December 2014)

[21] Ebola tracking system for Sierra Leone offered by IBM (BBC News, 27 October 2014)

[22] Boima Tucker Beats, rhymes and Ebola (Cultural Anthropology, 7 October 2014)

[23] GAIA brings educational textile design to the field of public health (Global Alliance to Immunize against Aids, accessed 12 April 2015)

[24] Information note: Ebola and food safety (WHO, 24 August 2014)

[25] Ebola (Institute of Development Studies, accessed 16 April 2015)

[26] Obinna Anyadike Ebola, is culture the real killer? (IRIN, 29 January 2015)

[27] Clare Chandler and others Ebola: limitations of correcting misinformation (The Lancet, 4 April 2015)

[28] Andrew Gumbel Disneyland measles outbreak leaves many anti-vaccination parents unmoved (The Guardian, 25 January 2015)

[29] Barry S. Hewlett and Richard P. Amola Cultural contexts of Ebola in Northern Uganda (Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2003)

[30] IRC community-partnership approach helps reduce Ebola spread in targeted West African communities (International Rescue Committee, 9 October 2014)

[31] Kulsoom Rizvi The IRC and partners pilot a community ‘early warning system’ for Ebola (IRC, 9 February 2015)

[32] Ebola response: triggering local communities to prevent Ebola (Restless Development, accessed 12 April 2015)