Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The virus that causes Zika fever can be transmitted through sexual contact long after initial infection as it survives for weeks in semen, according to research undertaken in Brazil.

A paper published this month in Clinical Infectious Diseases found nine cases of sexual transmission of Zika virus. The initial infections were acquired by men who travelled to regions where Zika is circulating. They then passed it to their partners, who could not have contracted the disease any other way.

The virus was identified in the individuals through molecular biological tests. One man still had the virus in his semen 62 days after the onset of symptoms.

“It indicates a much larger infectious period during which the virus could be transmitted.”

José Moreira, National Institute of Infectious Diseases Evandro Chagas

“It indicates a much larger infectious period during which the virus could be transmitted” than the time it is active in the bloodstream, which is usually no longer than seven days, says lead author José Moreira, a researcher at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases Evandro Chagas, a unit of Brazilian public health institution the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

He says the virus may be surviving in some kind of ‘viral reservoir’: a hidden region of the body that immune cells cannot reach.

The cases of sexual transmission of the virus were from men to women after they had unprotected vaginal sex, although there is evidence that the virus can also be transmitted by unprotected anal sex between men, the researchers say.

Moreira adds that mosquitoes are still the main driver of transmission and that it is not yet possible to say whether the babies of women who contracted the virus through sexual transmission are more prone to develop malformations than those bitten by infected mosquitoes.

Last month, the World Health Organization said there was no longer any doubt that the Zika virus causes babies to be born with microcephaly: abnormally small heads with associated brain damage.

Earlier this month, a group of Brazilian researchers demonstrated the harmful effects of Zika virus on human brain cells.

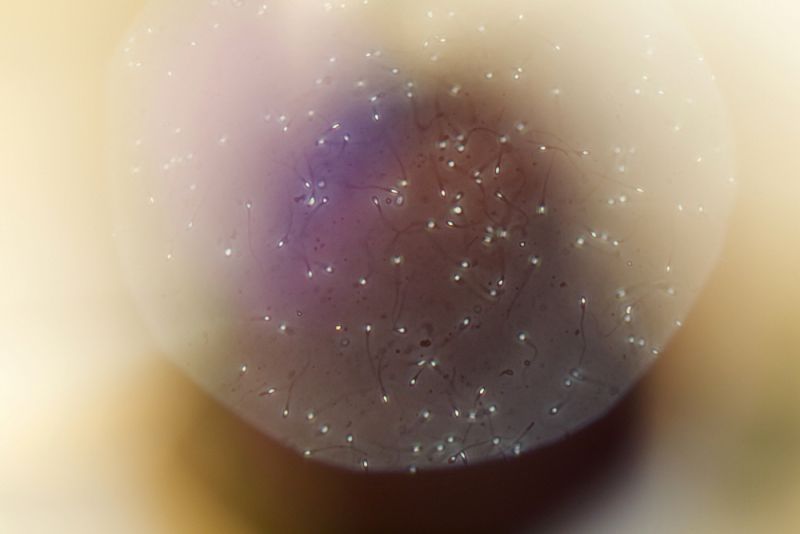

In a study published in Science on 10 April, they infected ‘neurosphere’ cultures of brain cells with the Zika virus isolated from a Brazilian patient. The virus killed most of the neurospheres and left the few survivors small and misshapen.

“The affected neurospheres degraded within six days, whereas those originating from uninfected cells developed normally,” says coauthor Stevens Rehen.

References

[1] José Moreira and others Sexual transmission of Zika virus: implications for clinical care and public health policy (Clinical Infectious Diseases, 5 April 2016)

[2] Patricia P. Garcez and others Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids (Science, 10 April 2016)