07/07/16

The genetic hunt to take down Chagas disease

The Triatoma infestans bug, one of 120 blood-sucking species of insects that carry the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite responsible for Chagas’ disease

Jon Spaull

Triatoma infestans is a major cause of illness in Latin America. It almost exclusively lives in poorly constructed homes. In some areas in Brazil and Paraguay, up to 80 per cent of the bugs carry the Chagas parasite

Jon Spaull

Bolivians sleep in a mud hut. The bug hides during the day in cracks in the walls that mirror its natural habitat of rock crevices. During the night, it emerges to feed on sleeping humans. It often feeds on people’s faces, hence its popular name: the kissing bug

James Morgan/Panos Pictures

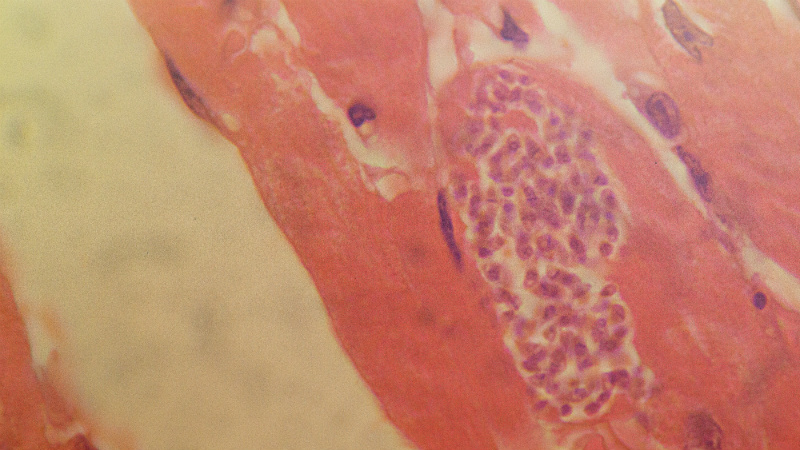

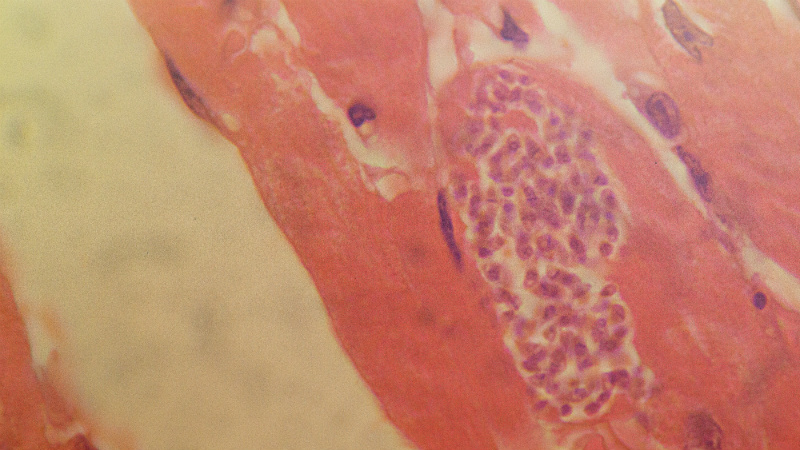

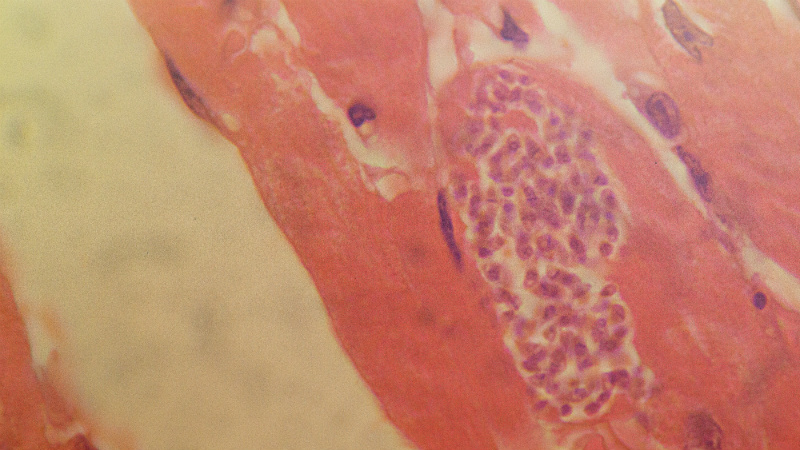

A microscope image of a section of infected mammal cardiac muscle. The parasite enters a cell and then multiplies, forming what is called a pseudocyst (seen on the right). This comprises up to 400 parasites in a single cell. Eventually, the cells rupture, releasing parasites into the bloodstream

Jon Spaull

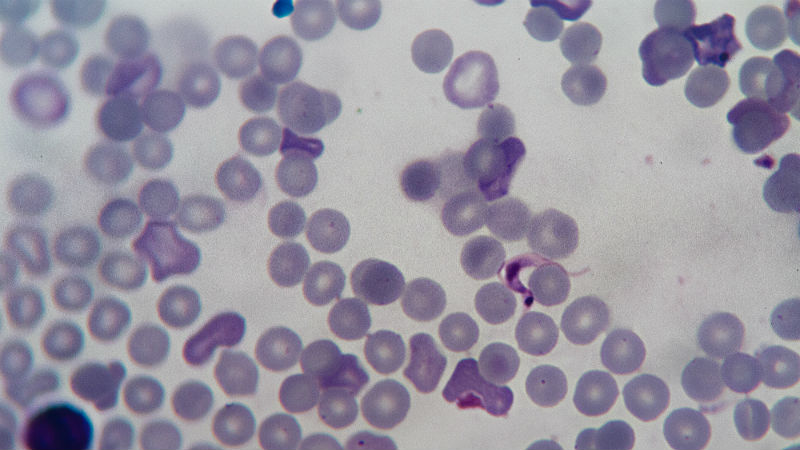

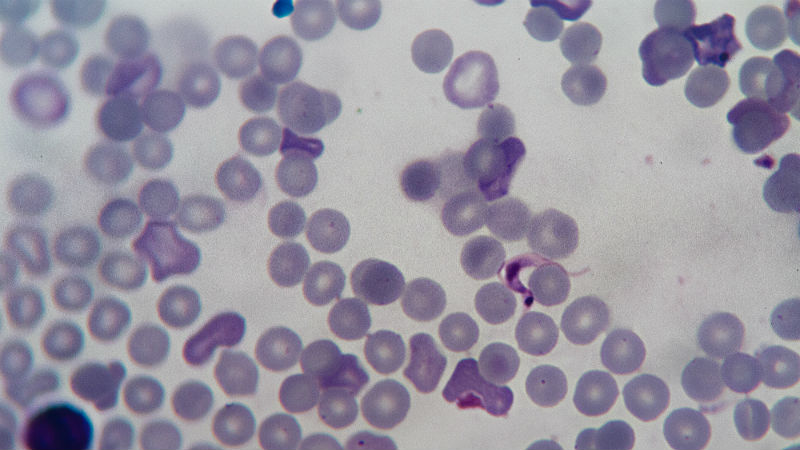

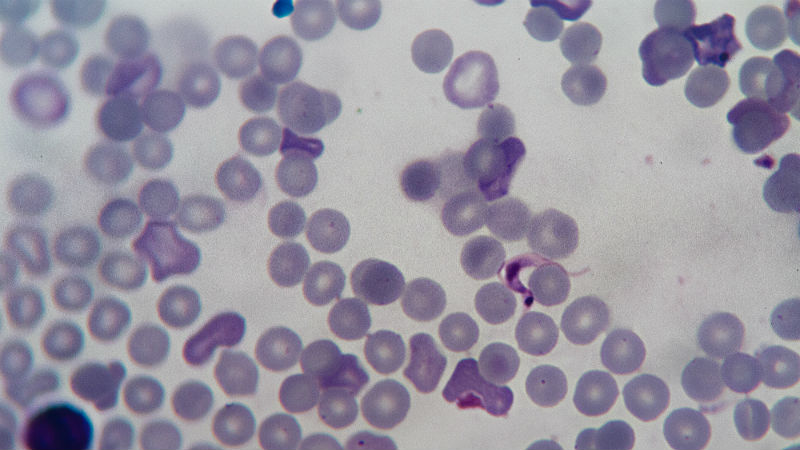

This microscope image shows the parasite (the purplish, sickle-shaped object towards the right amid round red blood cells) at another stage of development. At this trypomastigote stage, it moves through the blood to find other cells to penetrate and then form a new pseudocyst

Jon Spaull

Rhodnius prolixus, another important Chagas vector, feeding on a hand in a lab at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the United Kingdom. The insect lives in homes with palm thatch. It is hard to eradicate because it also lives in palm trees, so it can reinvade once cleared from a dwelling

Jon Spaull

The insect’s abdomen has become swollen with blood from feeding

Jon Spaull

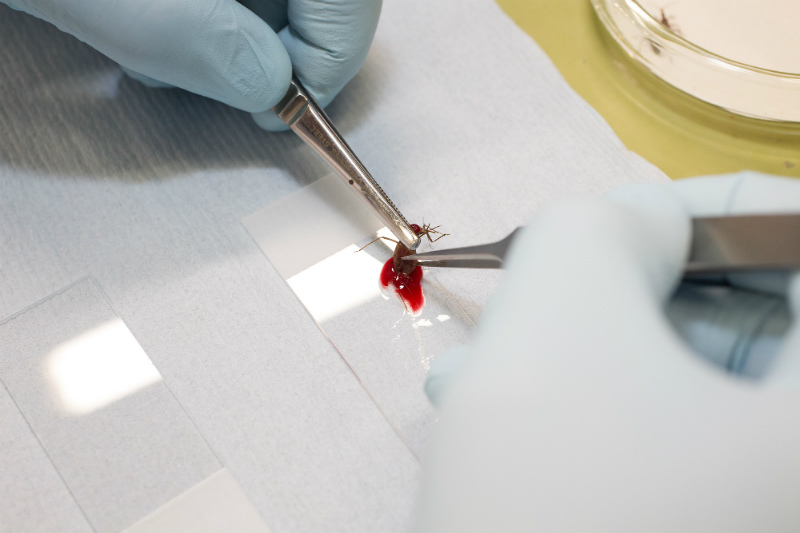

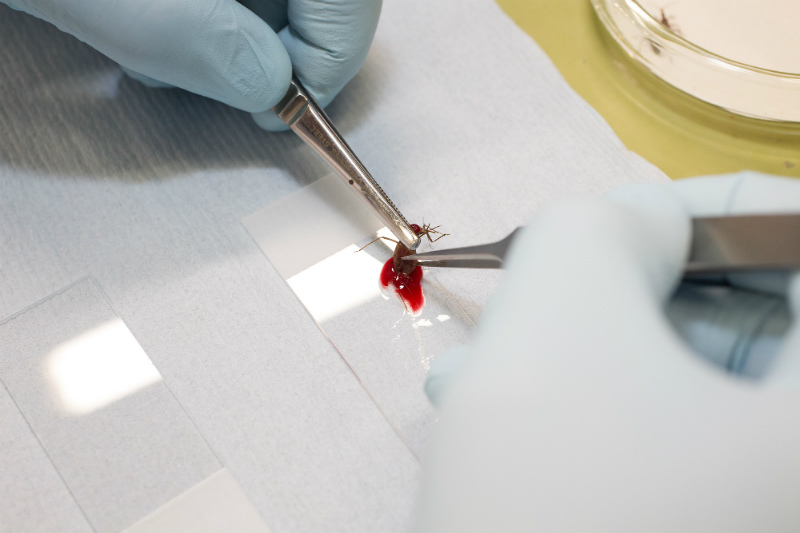

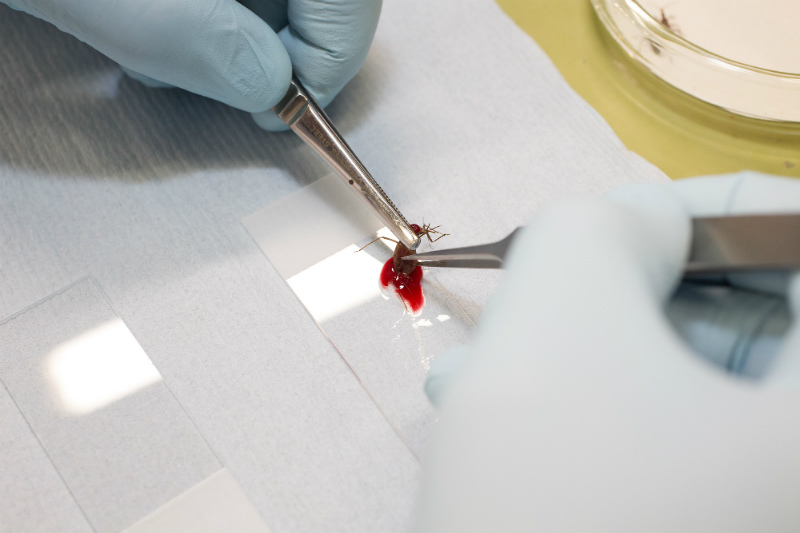

A researcher then extrudes the contents of the insect’s gut after it has been feeding

Jon Spaull

The gut contents are placed on a microscope slide for analysis. One way to diagnose Chagas’ disease is to place an uninfected bug on a person’s arm and then to examine the contents of its gut under a microscope for the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite

Jon Spaull

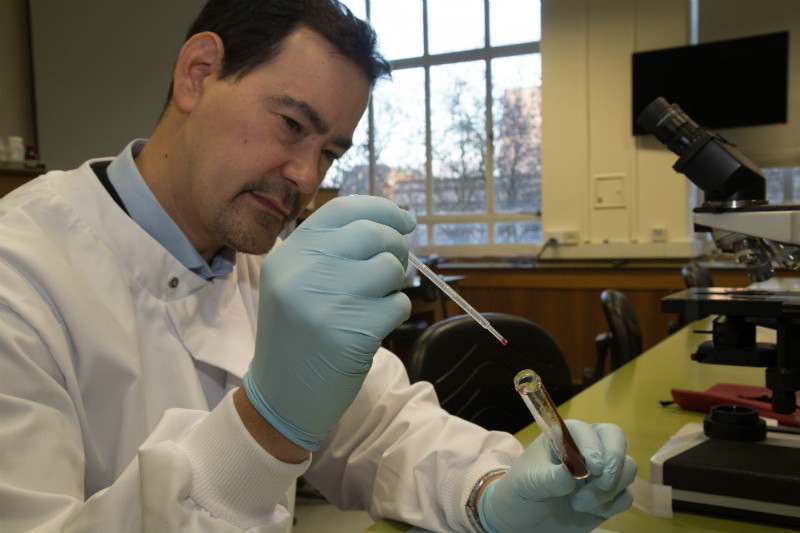

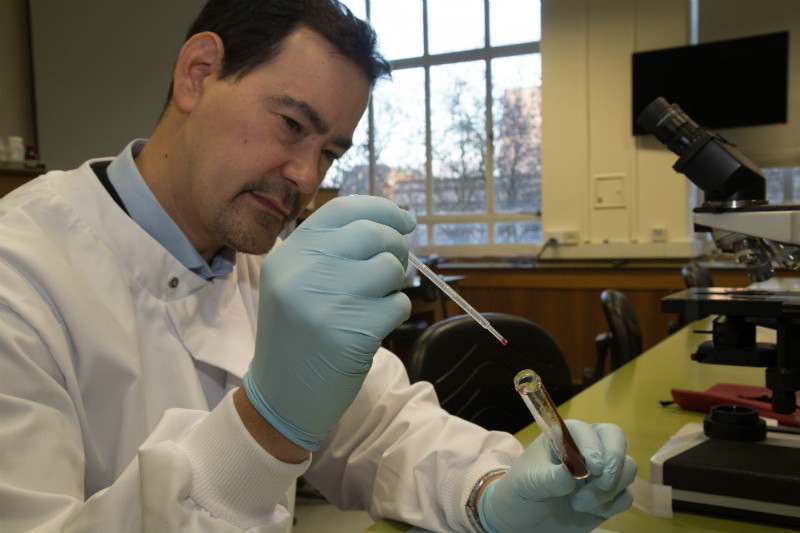

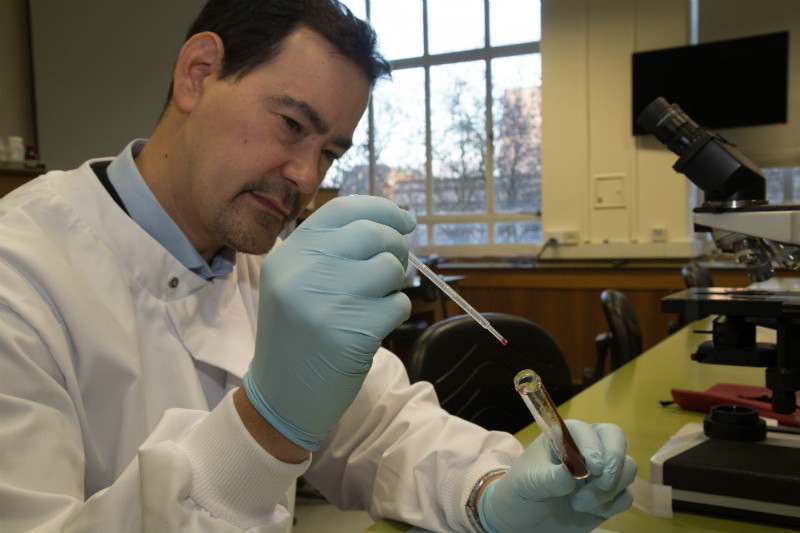

Researcher Matthew Yeo places the gut contents of a Chagas spreading insect in a test tube for DNA analysis. This can be used to ascertain the particular strain of parasite the insect carries, to assess if it is particularly susceptible to drugs

Jon Spaull

Yeo examines the parasite

Jon Spaull

By: Jon Spaull

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

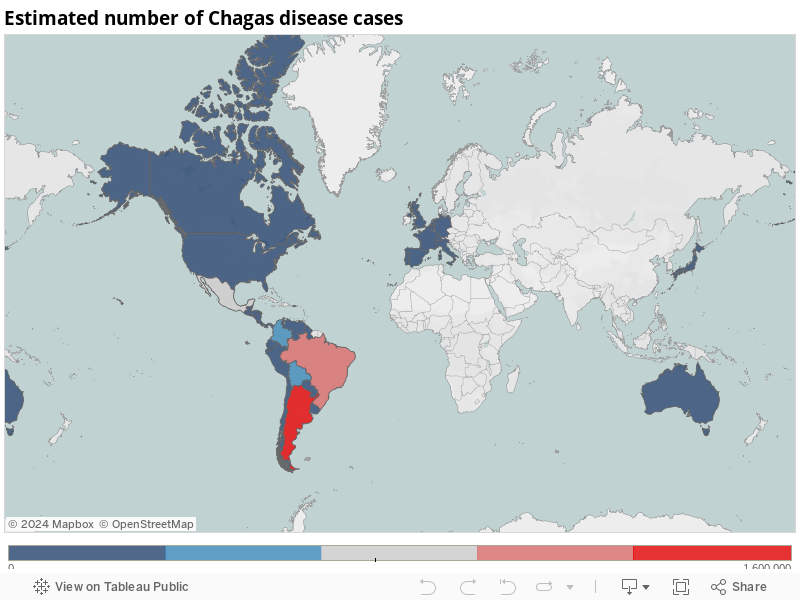

Anything between six and 11 million people worldwide are infected with Chagas disease, of whom at least 12,000 die each year. Yet the parasitic disease receives little attention, largely because it primarily affects poor Latin Americans.

This photo gallery follows the work of researcher Matthew Yeo at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, in combating this neglected tropical disease.

The disease is caused by the Trypanasoma Cruzi parasite and transmitted by Triatomine bugs. The bugs feed on the blood of mammals. When the bug feeds on an infected mammal it ingests the parasites which then multiply in the bug’s stomach. The infected bug then passes on the parasites to another mammal by defecating while feeding on the mammal’s blood. Although the parasite cannot be passed on through unbroken skin it can penetrate any wound or mucus membrane. The parasite can also be spread via oral contamination — through undercooked food that the bug has defecated in, congenitally from mother to baby and through blood transfusions.

These bugs live in houses made from materials such as mud, adobe, straw and palm thatch, which mirror their natural habitat. During the day, the bugs tend to hide in cracks and crevices, emerging at night to feed on the sleeping inhabitants. They often feed on people’s faces, hence their popular name: kissing bugs.

Although some infected people have no symptoms, about 30 per cent develop a chronic infection. The Chagas parasites infect and reproduce in the heart and intestines causing them to swell. This can lead to cardiac arrest, heart failure, altered heart rate or rhythm and difficulties in eating and defecating.

While there are drugs available that eradicate infections, they also harm the skin, brain and digestive system. They are also less effective the more time has elapsed since becoming infected. So the search is on for more efficacious and less-toxic drugs that can be targeted at particular parasite strains.

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine breeds the insect vectors, infecting them with the parasite to help improve understanding of the disease. Matthew Yeo is currently studying the parasite’s genetic diversity. There are at least six genetic strains that might cause different pathologies in humans.

According to some estimates the number of people infected with the disease has halved over the past ten years — partly because of a more effective strategy to contain the disease such as the use of bed nets and insecticide spraying, but also because a decade of economic development in Latin America has brought improved housing and living conditions.

Despite this, it is highly unlikely that Chagas disease will ever be eradicated because the parasite is found in more than 140 animal species. This means there will always be a reservoir of infected vectors. Spraying houses with insecticide to kill the bugs, using bed nets and screening blood donors are still the best ways to reduce the chances of infection.