Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

How to build better with less? Monica Wolfe Murray explores new trends and enduring challenges in shelter provision.

Shelter is a basic human need. Yet at the end of 2015, over 100 million people remain homeless, while almost 1-in-4 people on the planet — more than 1.6 billion — live in inadequate informal settlements that are unsafe, overcrowded and lack basic services such as water and sanitation.

Securing adequate shelter is a complex process: lengthy, costly and not entirely predictable. At best, multiple factors — social, economic, environmental and cultural — work together to turn a ‘shelter’ into a ‘home’, and much of the process of creating a ‘home’ remains outside an individual’s or community’s power.

Disasters add massive, urgent shelter requirements to the already vast and chronic shortage of housing in the developing world (box 1). But planning and rebuilding after disaster is also a vast opportunity: not only to build safer houses but also, and much more significantly, stronger, more resilient communities. This article highlights some of the traits, trials and achievements in providing shelter after disasters that could provide inspiration, lessons and tools in the effort to secure safe homes for all those who need them.

Alarming trends

The vast global mission of securing shelter is unfolding against an alarming background — a ‘perfect storm’ driven by converging and escalating challenges.

The world’s population is increasing dramatically, with the fastest growth recorded in resource-poor countries. [1] The challenge of ensuring adequate homes for the added millions is staggering. UN-Habitat estimates that an additional three billion people will need housing by 2030. [2] Ten years ago, it calculated that meeting that target required building 96,150 houses every day (or 4,000 every hour). [2,3] These staggering numbers must be even higher now.

More than half of all humanity lives in urban areas. In developing countries, rampant urbanisation translates into burgeoning slums and misery. The mission of planners and builders, in a century of cities, is to provide housing, infrastructure and income opportunities to urban migrants and young adults.

Then there is climate change. Its effects are growing more intense and frequent: extreme weather is fast becoming the new norm. Destructive climate-related events take a higher toll in resource-poor countries, where people are more likely to live in unsafe structures and hazardous locations, without any savings, insurance or guaranteed incomes. It is much harder for them to replace lost homes and get back on their feet after disasters. Conflicts and disasters in the developing world have the insidious impact of deepening and perpetuating poverty, and eroding community resilience. In poor areas, disasters take more lives, wipe out assets and wear down people’s capacity and confidence to recover. And aid funds are dwindling just as relief and recovery needs are growing. It is clear that, in coming years, much more will have to be achieved with fewer resources.

(Text continued after graphic)

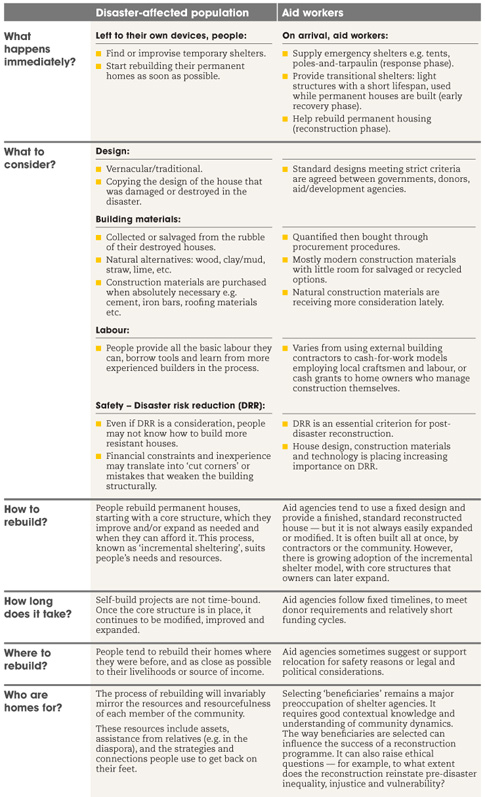

Shelter after the storm

The goal is to produce not only more houses, but houses that are safe, affordable — also quick to build and easy to replicate, expand and maintain by the very people who need them. Although each humanitarian reconstruction programme is unique, there are a few trends to how shelter is built after a disaster and how the sector has developed over time. Table 1 summarises options and scenarios for shelter recovery, outlining what aid agencies and the affected communities tend to do after a disaster. They are based on case studies, practitioners’ testimonials and the authors’ own expertise with shelter reconstruction programmes. Inevitably, it generalises to indicate trends, so it is worth noting that strategies and programmes are changing as insight and experience deepen over time (current trends are discussed later in this article).

Table 1: Shelter after disaster — two perspectives

High-tech versus traditional

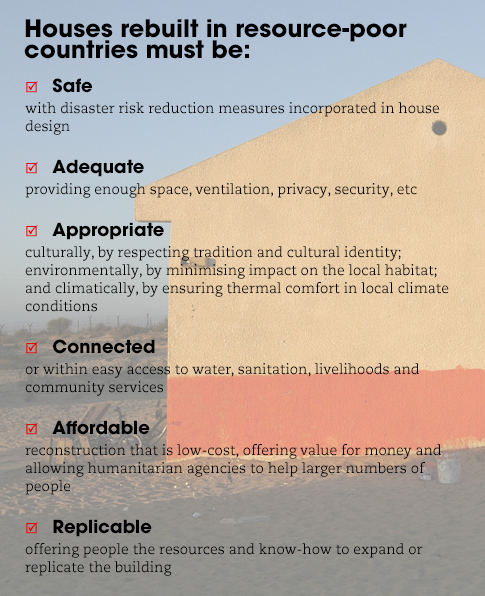

It is clear that rebuilding after a disaster is a complex task. New houses need to meet numerous criteria before they can be deemed safe and well-suited to the owners’ needs (box 2). [4]

Box 2.

Humanitarian workers have explored the prospect of innovation in approach, building design, materials or technology for shelter construction that meets these requirements. But is technological innovation the key to securing adequate shelter for the billions of people who need it, and can it support them on the journey out of poverty and extreme vulnerability?

The term ‘innovation’ can cover a wide scope of meaning: anything from a clay-and-lime building block to a 3D printed house can be described as ‘innovative’. In the shelter sector, design and technology innovations are pulling practitioners in opposite directions: a return to the vernacular on the one hand, and new designs, materials and technologies on the other.

Return to the vernacular

Increasingly, humanitarian workers are looking to traditional house designs and building techniques to inspire the type of simple, low-cost innovation that would have the largest impact. This approach has considerable advantages. Vernacular construction is affordable, culturally appropriate, easily replicable, environmentally friendly and well-suited to different climates (box 3). It often uses natural, sustainable materials sourced locally, and it can be adapted and expanded incrementally, to fit the owners’ needs.

Box 3: Pakistan reconstruction after the floods, 2010-2014 [5] |

| In 2010, the monsoon brought floods and devastation to the vast agricultural lands along the Indus valley. Two million houses were destroyed. Reconstruction started as a conventional programme — producing standard brick-and-cement houses — but soon turned to traditional materials and vernacular design to improve efficiency and impact.

Several small changes were made to traditional house designs: earthen walls were stabilised and strengthened with lime — a cheap, local material that massively improves water-resistance and reduces the environmental impact of the building process; wider roofs were built, with protruding eaves to protect the walls from the rain; the floor level was raised by building a ‘toe’ from earth and lime — which offered protection from stagnating water. Local building materials were used whenever possible: earth, bamboo, lime, timber, thatch and straw. Using conventional methods would have perhaps allowed aid agencies to house 35,000 families. By using vernacular designs and technologies instead, they were able to assist over 107,000 families and the cost of rebuilding one house fell from £750 to £200-250 (approximately US$1,160 to US$300-400). Overall, providing housing to 107,000 families using conventional reconstruction protocols would have cost US$77 million more and released an additional 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. |

Drawing from much earlier ages of construction can also provide viable alternatives to unsustainable materials and methods. One such example is seen in Africa’s semi-arid regions, where the timber-intensive traditional building style depletes forests and is increasingly costly. An ancient construction technique from upper Egypt — the Nubian Vault — has inspired durable houses built with local, natural materials such as mud bricks and earth mortar at much lower costs. The method is used in six countries and continues to spread across the continent.

New designs and technologies

At the other end of the spectrum, housing experts and businesses propose new designs, construction materials and technologies to respond to shelter crises in resource-poor countries.The range of ideas is vast, with some bold solutions offered to meet urgent or long-term needs. Abeer Seikaly’s award-winning tent design, for example, uses durable, cutting-edge materials in a traditional weaving pattern to produce an emergency shelter that is weatherproof and solar-powered. Flat-packed transitional shelters are an example of lightweight housing units that are modular, and easy to transport and assemble. And a growing number of companies are beginning to showcase 3D printed permanent houses which, they maintain, make the task of reconstruction after disasters much easier. But this hypothesis remains untested in a humanitarian scenario (see box 4).

These solutions are undoubtedly ingenious in addressing one or more of the reconstruction challenges detailed in box 1, but it is often the criteria they don’t meet that determine their fate.

Are they safe? Can these buildings be maintained, replicated or expanded by their owners? Are they affordable? How quickly and cheaply can they be transported and assembled? People funding and implementing humanitarian responses will ask all these questions, and more, before a new design can graduate from the drawing board to be tested and finally applied at scale in a crisis situation.

Experience also shows that communities will reject designs that do not fit their culture, needs and aspirations. And aid workers justly question the ethics of testing new housing inventions on disaster-affected people who can have no say in the process.

Box 4: 3D Printing: Potential and pitfalls |

| It is hard to ignore the potential of 3D printing in various sectors of humanitarian action — from healthcare to providing water, sanitation and shelter. Would it be unrealistic to imagine that the entirety of shelter assistance after a disaster could consist of shipping a 3D printer to the affected area and getting to work?

3D printers could produce a permanent house in one day, using natural, local materials such as earth or sand. The designs can be tailored to suit needs and cultural criteria. It is impossible to estimate the costs of the technology itself, but some believe funds could be saved by bypassing costly transitional stages of shelter assistance. On the downside, 3D printed houses have no track record of durability or safety, and there are ethical concerns about testing them on people who have no choices. People could never replicate, expand or maintain them. And, most significantly, providing such shelters needs less community participation or contribution than other approaches. It is, once again, a product, rather than a community-building process. |

However exciting, beautiful or promising they are, most of the ideas and prototypes proposed by affluent countries are rejected by shelter practitioners working on real life situations in the developing world. By contrast, more modest approaches continue to gain ground and popularity. These solutions are often small and simple, low tech and low-cost; make vast improvements to the quality of housing; are applicable widely and by anyone; and impose the lightest possible burden on the environment.

Building change

Beyond innovations, the essential issues and challenges of providing shelter are the same as they were five decades ago. Learning is not easy to transfer and replicate because each situation has its own context. To be successful, each reconstruction or building programme needs to resonate with a complex and ever-changing background of economic, political, social and environmental realities.

These multifaceted and unpredictable settings make it challenging for aid or development agencies to gather evidence, compare, learn or standardise — the wheel needs to be reinvented, to a degree, each time. Still, although there is no blueprint that fits each context, there are common principles and parameters to guide shelter planning and design.

Over the past decade, programmes have begun to place the people who need shelter at the helm. The notion that people affected by disasters, conflicts, urban hardship and poverty can rebuild their own homes is not new. But perhaps it is only now that shelter organisations are allowing it to inform their strategy. They acknowledge that everyone has the right to a home that is safe and culturally appropriate, a home that meets their needs and aspirations. Once this basic premise is established and agreed by all, some guiding principles become amply clear.

First, shelter is a complex process, not a humanitarian product for distribution. Donor and accountability requirements make it all too easy to treat shelter as a product to be ‘delivered to beneficiaries’. But this top-down, donor-driven, paternalistic approach has often excluded prospective house-owners from every decision, as well as the building process itself. This can lead to tensions or conflict. After the Indian Ocean tsunami for example, while commercial contractors landed on islands in the Maldives to build standard houses designed by government engineers, inhabitants could only observe, argue and complain about every detail and aspect of ‘their’ reconstruction. This approach is gradually changing. Instead of talking about ‘housing units delivered’, shelter reports now refer to ‘people assisted’. [6]

Second, building shelter is a ‘people-owned process’. Recovery after a disaster is faster and more successful if community members can make decisions about, and lead, the reconstruction. Humanitarian workers and donors are learning to place equal if not more weight on ‘soft’ approaches including informing, engaging, training and empowering communities to rebuild their own homes. Nepal’s post-earthquake reconstruction strategy — cash grants and training — is the latest example of this approach.

Third, people want ‘homes’, not ‘housing units’. Humanitarian workers increasingly act from an understanding that a ‘shelter’ becomes a home only when several essential needs are met: livelihoods, infrastructure, essential services and legal status, economic resilience and environmental sustainability. In rural Pakistan, for example, after three years of severe flooding (2010-2012), house reconstruction efforts by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development also supported agriculture, tree planting, kitchen gardens, water and sanitation, rebuilding infrastructure and disaster risk reduction measures. [5]

Immediately after the floods, NGOs distributed kits for emergency shelter, consisting mainly of bamboo poles and tarpaulin. These materials were then reused to build permanent houses. Community-based organisations managed cash grants to rebuild their homes in a process that increased people’s confidence in their own resources, skills and resilience.

Finally, the built environment affects people’s vulnerability to natural hazards. There is a fundamental difference between hazards and disasters: hazards are unpredictable natural threats — earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions; it is development decisions such as where and how to build a home that can turn these unrealised threats into disasters. It is the buildings themselves that define how vulnerable their inhabitants are and what risks they face.

This underlines the opportunity and responsibility to rebuild safer houses after disasters. The first task is to identify measures that make construction better and safer, and to get these measures adopted among the community’s building practices. For example, after Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, eight basic measures were promoted to increase the safety and resistance of new buildings. The very simple approach of publicising key messages can have a vast impact on people’s awareness and building techniques.

The future of shelter

People will always find ways and resources to secure shelter, however unsafe and inadequate, and whether in dense urban environments or amid the utter devastation of disasters. And whatever the context, the biggest challenges remain the same: rebuilding with an understanding of risk and environmental impact, and seeing housing as a part of a community’s resilience, along with other components such as livelihoods, health and culture. Securing land tenure and access to financing are additional, and crucial, challenges.

Some of the shelter solutions used by the humanitarian sector after disasters now inspire and inform people working to address the long-term, chronic housing shortage in urban areas. Specific urban realities, such as high density and complex infrastructure needs, make a simple transfer of a shelter model unworkable, but a people-centred shelter approach can work for urban dwellers too.

For example, research by Arif Hasan and his team in Karachi slums has shown that relocation to apartment blocks — the planners’ solution — typically leads to more poverty and isolation. Instead, planning for low-income urban settlements that can be expanded incrementally by those who occupy them — an owner-led approach — facilitates economic and social progress. [7]

Meanwhile, in cities, architectural firms continue to propose highly technical alternatives to urban slum housing, such as futuristic-looking skyscrapers that use recycled shipping containers as building blocks to provide a type of transitional shelter to replace slum housing. But do these suit people’s needs, lifestyles or livelihoods? Most likely not: they are costly to build and completely outside the control or culture of the potential inhabitants.

Providing homes to the billions of people who need them remains a complex and overwhelming challenge. But decades of assistance in urban and rural areas following disasters, migration or economic hardship, have shown that the biggest impact comes not from technology, but from involving communities in building their own homes. Real progress tends to come from small, simple improvements in design that everyone can use, a return to the traditional and the natural, care for safety and the environment and, most importantly, engaging families in creating their homes and habitats.

Monica Wolfe Murray is a writer and editor, and formerly programme design and implementation advisor at UN-Habitat. She can be contacted at [email protected]

| Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Adaptation (to climate change) | The ways that natural and human systems adjust to changing climatic factors in order to mitigate harmful impacts or exploit opportunities to thrive and develop. |

| Build Back Better/Build Back Safer | An approach to shelter reconstruction that aims to reduce vulnerability to natural hazards and improve living conditions, but also to promote a more effective rebuilding process. The term also describes solutions and details incorporated into house design and building technologies for making houses more resistant to natural disasters. |

| Building code | A set of regulations and standards to control aspects of the design, construction, materials, alteration and occupancy of housing. The goal is to ensure they are safe by, for example, making them resistant to collapse, damage and fire. |

| Climate change | A change in the earth’s climate in addition to natural variability and related directly or indirectly to human activity. The term describes changes that persist for decades or longer, and alter the composition of the global atmosphere. |

| Construction technology | The choice of building materials, techniques and other methods used to erect or repair a house. |

| Disaster | An unforeseen and often sudden event that combines with vulnerability to seriously disrupt how a community or society functions, beyond its ability to cope using its own resources. It involves loss of life and other impacts to human wellbeing together with damage to property and other assets, loss of services, social and economic disruption and environmental degradation. |

| Disaster risk reduction (DRR) | The theory and practice of reducing potential disaster losses by systematically analysing causal factors and corresponding measures that could mitigate the risk, such as wise environmental management and improved preparedness. |

| Displacement | Forcible or voluntary movement of people away from their homes. Those who remain within their country’s borders are known as internally displaced persons and those who flee outside the borders are known as refugees. Displacement may be caused by disasters, conflict, human rights violations or other traumatic events. |

| Hazard | A term that describes potential threats to people, the environment and the economy that are not always predictable. A hazard can be climatological, geological, hydrological or biological. |

| Housing | The immediate physical environment, both within and outside of buildings, in which families and households live and which serves as shelter. |

| Incremental sheltering/incremental housing | A process that draws inspiration from, and supports, the way informal settlements grow — starting with a one-room ‘core’ shelter and then adding extra units and functions as needs arise and when resources are available. It is increasingly supported as a low-cost solution that empowers communities, especially in urban areas. |

| Infrastructure | Systems and networks by which public services are delivered, such as water, sanitation, energy, utilities and transport. |

| Land tenure | A term that describes the legal regime in which land is owned, with an individual said to hold the land. |

| Livelihoods | A combination of the resources and activities that ensure survival and wellbeing. Resources include individual skills (human capital), land (natural capital), savings (financial capital) and equipment (physical capital), as well as formal support groups and informal networks (social capital). |

| NGOs (non-governmental organisations) | Not-for-profit entities that are independent from a government or state. They are normally devoted to humanitarian and human rights causes. Local and international NGOs play an important role after disasters: they coordinate activities, provide services and take measures related to emergency relief and longer-term recovery. |

| Reconstruction | The restoration and improvement of physical structures, services and infrastructure that has been destroyed or damaged in a disaster. The term also includes the restoration of facilities, livelihoods and living conditions of disaster-affected communities, and efforts to reduce disaster risks. There are different approaches to reconstruction. It may be driven by home owners and communities rebuilding with or without external assistance, or it may be driven by an agency contracting the reconstruction out to private companies with little or no involvement of the community and home owners. |

| Recovery | Actions taken after a disaster to restore or improve pre-disaster living conditions, with adjustments to reduce future disaster risk. The term includes not only physical reconstruction but also restoration of livelihoods, the economy, social and cultural life. |

| Relief or response |

The provision of emergency assistance during or immediately after a disaster to save lives, reduce health impacts and meet the basic needs of those affected. This type of intervention can be brief or protracted, depending on the situation. |

| Resilience | The ability of a system, community or society to resist, absorb, adapt to and recover from the stresses of a disaster. Resilience depends on the degree to which the system has the resources, social capital and organisational capacity needed to recover from any type of shock. |

| Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction | The agreed global framework of voluntary actions to reduce disaster risks from 2015-30. It was adopted in March at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai, Japan. |

| Shelter | A habitable, covered living space that provides a secure and healthy living environment, with privacy and dignity for people who reside within it. Used after a disaster, the term is defined more broadly and covers the physical protection needs of people who no longer have access to their homes. Immediate post-disaster needs are met by emergency options such as tents or basic shelter kits containing tarpaulin or plastic sheeting and poles. More resistant but lightweight, short-term shelters such as prefabricated housing units — known as ‘transitional shelters’ — are used until a durable, permanent structure is restored or rebuilt. |

| Shelter Cluster | A mechanism that helps improve coordination among governments and others working in the shelter sector, so that people who need assistance get help faster and receive the right kind of support. IFRC convenes the Cluster in natural disasters while UNHCR leads in conflict situations. |

| Sphere standards | An abbreviated popular term for the Sphere Handbook — a widely accepted set of principles and minimum standards for delivering an adequate humanitarian response. It includes guidelines for the planning, construction and environmental impact of shelter reconstruction. |

| Vernacular architecture | A term that describes buildings which use traditional technologies and local construction materials. It reflects the specific needs, values, environmental context, economies and ways of life of the culture that produces these buildings. They may be adapted or developed over time as needs, resources and circumstances change. |

| Vulnerability | The characteristics and circumstances of a community, system or asset that make it susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard. Vulnerability varies within a community and over time. There are many aspects of vulnerability in relation to shelter and disasters — examples include poor design and construction of buildings, lack of public information and awareness, and limited official recognition of risks and preparedness measures. |

This article is part of our Spotlight on Shelter crisis: Rebuilding after the storm.

References

1] World population prospects: the 2015 revision, key findings and advance tables. (UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2015)

[2] Financing urban shelter (UN-Habitat, 2005)

[3] Housing and slum upgrading (UN-Habitat, 2005)

[4] Humanitarian Shelter Working Group Recovery shelter guidelines (Shelter Cluster, 2006)

[5] Improved shelters for responding to floods in Pakistan (ARUP, 2014)

[6] Shelter projects 2013-2014 (IFRC, UN-Habitat and UNHCR, 2014)

[7] Arif Hasan and others Planning for high density in low-income settlements: four case studies from Karachi. (IIED, 2010)