By: Mićo Tatalović

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

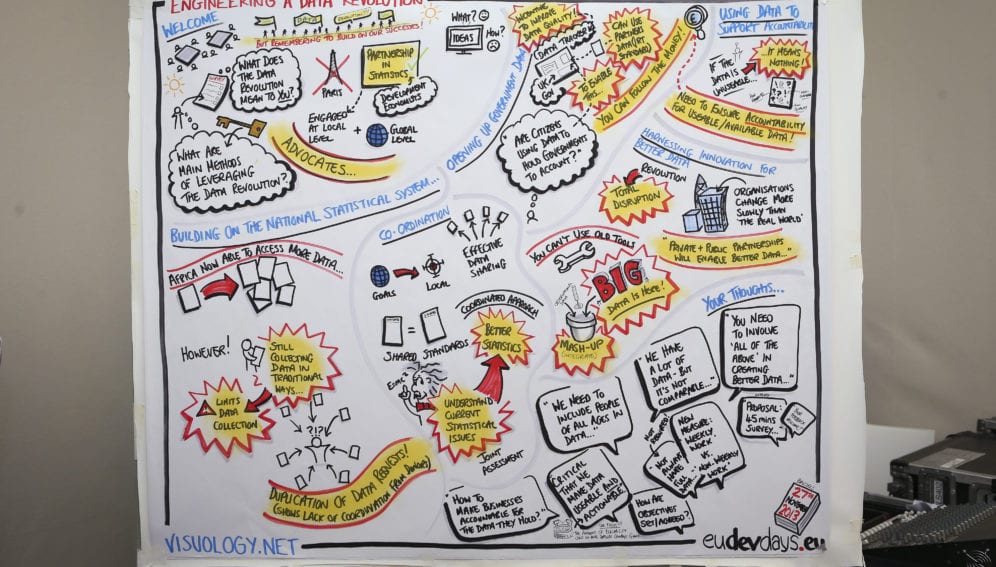

It’s all very well calling for a revolution in data for use in post-2015 development, but what might such a revolution involve? The UN high-level panel report, which called for such a revolution earlier this year, gives little in terms of specifics, and the term itself was coined to get people talking, a European Development Days 2013 meeting heard last week (26-27 November).

So what is actually needed to get better use of digital data in development?

The key messages coming out of the meeting were that support needs to be given not only to the national statistical offices in developing countries that are currently ill-equipped and reluctant to partake in such a revolution, but also to make sure there is a demand for such data from citizens and that the final packaging of data is easy to use and practical for improving delivery of public services and improving lives.

As one participant said, the key is to make data usable, “otherwise data will remain just data”.

Edit Jibunoh, global policy director at ONE, an anti-poverty campaigning and advocacy organisation, illustrated this with an example from Nigeria, where the finance ministry published data on a monthly basis — so providing open and accurate data — but in an unfriendly format and in print, meaning “no one ever used them as they did not make sense to people”.

What is needed instead is “actionable data” in a format that both makes sense and is relevant to people, she said.

Electricity data may not be in high demand, but when they were presented earlier this year as showing that Liberia’s yearly electricity spend is equivalent to that spent on the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium in the United States on a single game day, they went viral.

Supply and demand for data need to come together, but when they do, they will allow people to follow the money, monitor the effectiveness of governance and identify inefficiencies, Jibunoh said.

Getting local buy-in

Another big question in the upcoming data revolution is how to bring the national statistics offices onboard, making them friends, rather than foes, of the transformation.

Shelton Kanyanda, regional programme director at PARIS21, an organisation that aims to improve lives through better use of statistics in decision-making, and former chief statistician of the Malawi National Statistical Office, said statistical offices in most developing countries are still collecting most of their data via traditional means — physical collection — rather than using modern technology.

But they are not solely to blame for resistance to change — indeed many have seen progress, sharing more data and setting up websites in recent years.

Yet low or inconsistent government funding is limiting the expansion of what they can do.

And international organisations and donors are adding to the burden by asking for data sets — often different sectors ask for similar data sets from the same stats office. Ad hoc surveys commissioned by such international organisations lead to data duplication and an added burden on respondents, too.

An example of good practice to avoid that is the coordination of UK and Norwegian aid to Malawi’s statistics office, Kanyanda added.

The impending data revolution will need to see more donors do a much better job of coordinating their demands on stats offices.

Nicoleta Merlo, deputy head of the policy and coherence unit at EuropeAid, the European Union’s development policy body, said a joint assessment to identify the issues in need of addressing could lead to much-needed national strategies on the development of statistics.

But she highlighted that donors need to not only coordinate the supporting supply of stats but also their use and the creation of demand for them, which then creates a culture of evidence-based policy.

Donor-country leads

Nick Dyer, from the UK Department for International Development, said all nations have to start by “putting their own house in order” before they start “preaching” to others. And they have a long way to go — even the United Kingdom, which is considered to be a leader in providing transparent and usable data, is seeing through that work just how much improvement is still needed, the meeting heard.

“This has absolutely transformed the way we view our own data.”

Nick Dyer, DFID

The UK’s Development Tracker is available online to everyone. Another similar tool presented at the meeting is the European Commission’s EU Aid Explorer. Both include information on when, where and how the aid money was used and both attempt to visualise the information either through maps or infographics.

This visibility drives continual improvement, Dyer noted. “This has absolutely transformed the way we view our own data,” he said. “If you expose yourself to transparency” this leads to organisations scrutinising that data and leading to further improvement in the quality of data.

The ‘revolutionary’ fight ahead

But not everyone is convinced that it will be easy to get the stats offices onboard. Robert Manchin, chair and managing director of the Gallup Organisation Europe, said the data revolution may “unite statisticans in anxiety and disruption”, and that they may be slow to change.

Yet change is inevitable, as many current tools for data collection stem from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and those hoping the data revolution will go away may be out of luck, he added.

Nicolas de Cordes, vice-president of marketing vision from telecom firm Orange, said their experience in trying to engage the national statistics office in Côte d'Ivoire during their Data for Development challenge was that the stats office was not really interested in “your big data”; indeed such offices earn money by selling their services to international organisations, he added, and may see similar initiatives as a threat.

The challenge, he said, is “how to make it a believable story that this is not a threat but an improvement”.

In addition, the issue of data is very political, said Jibunoh, and a lot of countries are not incentivised to make data available — something that will need to change.

Finally, an idea, perhaps far-fetched, to push for an inclusion of a goal on raising data capacity and data revolution in the post-2015 framework’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), was mooted by the meeting’s chair, Johannes Jütting, manager of the secreteriat of PARIS21. Will it happen? We’ll have to wait and see.

But it’s worth keeping in mind that when the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were put together, information and communications technologies (ICTs) only got a single mention in one of the goals, and yet now they play a key role in achieving all of them, the meeting heard. Will big data become to SDGs what ICTs have been to the MDGs?

Link to UK Development Tracker

Link to EU Aid Explorer

Listen to a podcast from the meeting: