By: Holly Cave

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Donors and countries in Africa need “revolutionary” changes to turn the tide on “bad data”, as well as to insulate data from politics, according to a report on the data revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“Nowhere is the need for better data more urgent than in most African countries, where data improvements have been sluggish,” says the final report of the Data for African Development Working Group, published this month (8 July).

Funding for data collection is often unstable and inadequate, data accuracy is rarely checked, donors’ priorities sometimes overtake national ones, and national statistical offices lack incentives to improve, says the working group, co-chaired by the Center for Global Development and the African Population and Health Research Center.

“There is a need for some kind of performance-based approach to make NSOs incorporate quality into their products.”

Themba Munalula

Although data collection is happening — more than 80 per cent of African countries conducted a census between 2005 and 2014 — the report states there is a “paucity of reliable data” on key indicators of development such as maternal mortality.

And it adds that the early efforts have been “focused on collecting more — not necessarily better — data”.

“This may divert attention from the underlying problems surrounding production, analysis, and use of basic data that have inhibited progress to date,” it says.

Themba Munalula, a member of the working group and head of statistics at the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, a free trade area, says there is a lack of demand for data producers to monitor quality.

“There is a need for some kind of performance-based approach to make national statistics offices (NSOs) incorporate quality into their products,” he says.

The report highlights that the work of NSOs can be affected by politics and donor influence, and that there are still political incentives to “keep data hidden”.

The report says “it is hard to insulate data from politics”, and that “for political reasons, there are incentives to suppress or misreport certain national-level data. Examples include inflation and census data, especially where population size is used for budget allocation and allocation of parliamentary seats.”

These factors together with donor priorities that do not match local government needs mean that “NSOs lack incentives to improve national statistical capacity or prioritize national data building blocks, leaving core statistical products like censuses and vital statistics uncollected for years”.

“Perverse incentives can cause intentional manipulation, suppression, or misreporting of data for political or institutional gain,” it says.

“Both donors and countries need to do something truly revolutionary to address these core problems underlying bad data in the region,” the report says.

Independent data

It suggests that NSOs should therefore have more independence from government and donors.

Munalula believes that NSOs can achieve functional autonomy.

“In many instances, these agencies need restructuring; they require more professional staff and better facilities. The real challenge is whether governments will be willing to provide more funding as the NSOs change and improve.”

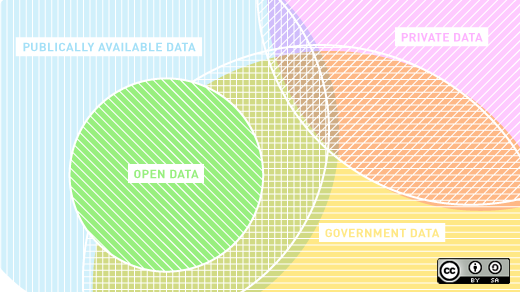

The report points to the need for free, publicly-available data as the end goal for a data revolution within Sub-Saharan Africa.

“Open data is not about taking the politics out of government, it is about making the politics more visible and helping people make decisions”, says Liz Carolan, international development manager at the Open Data Institute, in London, United Kingdom.

“However, public administrations are sensitive to risk, and releasing data can make leaders feel exposed,” Carolan adds. “With open data, they fear three things: criticism of data not being high enough quality; unwittingly enabling breaches of national security or personal privacy; and losing the power that comes from holding a monopoly on information.”

Governmental anxieties aside, opening up data should not yet be the primary concern in Africa, insists Munalula.

“Improving the production system — the compilation and dissemination of statistics — is the priority," he says.

> Link to Delivering on the Data Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa report